Document 13070899

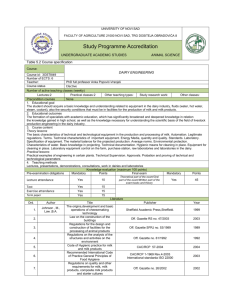

advertisement