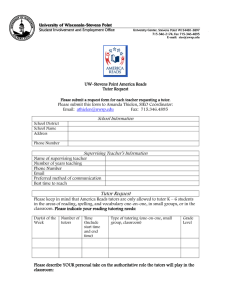

W C riting@the

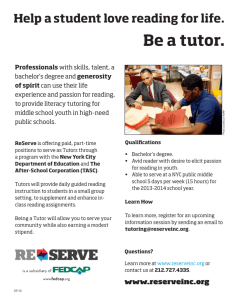

advertisement