Parental Choice of Preschool in Taiwan Submitted by Chia-Yin Hsieh

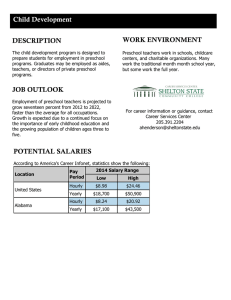

advertisement