Marine Biology

advertisement

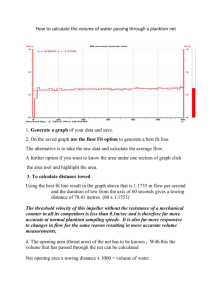

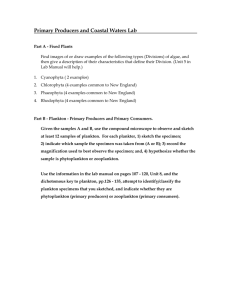

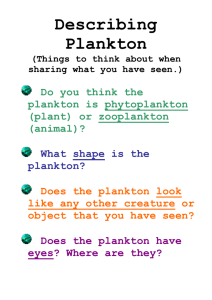

Marine Biology Invisible barriers in the ocean: how do the little things cope? Staying near the surface – why and how? Acidification – what does it mean? Chemical and physical forces are fundamental to the behavior of many marine organisms. In particular the smallest organisms, such as plankton, are at the mercy of ocean movement and stratification (layering of water by density differences). Plankton have evolved many strange shapes and adaptations to keep themselves near the surface, and to avoid being trapped in water layers that keep them from food or shelter. Other organisms, especially those with calcium carbonate shells, are very susceptible to ocean acidification, which makes it difficult for them to make those shells. Today you will be demonstrating water density and factors that affect density. You will also be building plankton of different sizes and shapes and making hypotheses about their sinking rates. During the lab, you will be watching a demonstration of ocean acidification. PART I: Water density – groups of 2 The density of seawater varies from place to place in the ocean, depending on evaporation and rainfall rates, river runoff, and water temperature. The density of the water in which marine organisms live influences several aspects of their lives, such as the flotation of planktonic forms. In addition, sinking masses of higher‐density seawater carry oxygen‐rich waters from the surface to greater depths, as less‐dense nutrient‐rich water moves upward. Finally, sinking of high‐density cold seawater in the north Atlantic drives the global circulation of water throughout the world's ocean basins. Today's lab exercise will demonstrate the relationships between water density, temperature, and salinity. There will be 2 large tubs with 2 large beakers each in them: TUB 1: Warm water (red) TUB 2: Cold water (blue) One fresh water One fresh water One salty water One salty water A. Temperature/salinity test 1. Fill a plastic cup with 50mL of the blue salt water, and fill another cup with 50mL of the red fresh water. **Remember you are trying to get the water to form layers due to density differences 2. Gently tilt both cups so that the liquids almost touch, and allow the red water to flow very slowly over the blue colored water. Gently place the full cup on the benchtop so everyone can see it. 3 Draw what you see in the space below. Label the two types of water and note whether there is a zone of mixing between them. B. Your own tests. Do 2 of these if time permits. Test for salinity too! 1. Fill a plastic cup with 50mL of the water you want to test, and fill another cup with 50mL of the other type of water you want to test. **Remember you are trying to get the water to form layers due to density differences 2. Gently tilt both cups so that the liquids almost touch, and allow the water to flow very slowly over the other colored water. Gently place the full cup on the benchtop so everyone can see it. 3 Draw what you see in the space below. Label the two types of water and note whether there is a zone of mixing between them. PART 2: Plankton – the great plankton race: groups of 2­4 The word plankton is from the Greek word for “wanderer”. They drift or wander the oceans and lakes at the mercy of the currents. They are generally unable to move against the currents, though some can swim (but not far!). The plankton that photosynthesize are called phytoplankton. The plankton that eat other plankton are called zooplankton, and are made up of tiny animals and single‐celled protozoans. Some ways the plankton slow their sinking rates and stay near the surface are: oil, high surface area (they are small), and increasing their surface area with spikes and weird shapes. Your task today is to build a plankton with your partners. Your plankton will be entered in a race, and the last one to reach the bottom of the tank will win. Bobbers (floaters) will be disqualified (eaten). Use the materials available to you. Keep in mind the importance of volume (keep it low), surface area (keep it high), and stuff that sticks out (increasing surface area). Your team will have 30 minutes to build and test your plankton. Then we will run three trials of the race, timing each plankton. Winner gets to gloat!! Why did the winner lose? What were the characteristics that made it win? Questions We conducted this experiment with fresh water, would there be a difference if we used seawater (salt water)? Why or why not? Why did we repeat the races several times? Why is it important for plankton to sink slowly? If they could not float, what would likely happen? What would you do differently now if you were going to create another plankton to race? Why? PART 3: Ocean acidification There will be one demo for ocean acidification set up in the front of the room. In this demo, we have yeasts undergoing respiration, which is producing Carbon Dioxide (CO2). This CO2 is dissolving into the water. It is reacting with H2O (water) and producing hydrogen ions, which increases the acidity of the ocean. Check the pH meter in the demo every 10 minutes and track the change. Make a simple graph of the trend you see. **Remember that pH is a logarithmic scale.