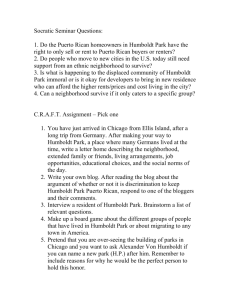

Graduation Ceremonies 10 - 23 Academic Oration

advertisement

Graduation Ceremonies 10 - 23 SIR TEMI ZAMMIT HALL – UNIVERSITY OF MALTA - MSIDA Academic Oration Dr Albert Gatt B.Psych.(Hons),M.A.,Ph.D.(Aberd.) “Between the devil and the deep blue sky” I would like to begin with a brief historical anecdote. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Wilhelm von Humboldt was invited to take up the role of head of section for ecclesiastical and educational affairs at the German Ministry of the Interior. An odd position to offer to a humanist with a universalist bent, known for his contributions to the study of language, science, political theory and culture, among other things; one who, as an associate of the Romantic school, kept the sort of company that for a state functionary might appear to be deeply suspect. I suppose that, even then, there was only so much of the spirit of Romanticism that state institutions could be expected to bear. No doubt, the appointment raised eyebrows in certain quarters, and that mistrust was apparently justified when Humboldt set about instituting radical changes in university education, in a spirit reminiscent of the writings of some German Romantics, such as Schleiermacher. His guiding principle was that the scientific institution should live and renew itself ‘on its own, with no constraint or determined goal whatsoever’. A far cry, it would seem, from developments that had been taking place in France, where Napoleon’s vision for the university made it the principal training centre for officers of state. Different as these two outlooks might appear to be at first glance, both had two aims in common, as philosophers such as Lyotard have noted. The first was to make knowledge somehow a legitimate pursuit: in one case – Humboldt’s – by defending a view that might be caricatured as ‘knowledge for its own sake’; in the other – Napoleon’s – by arguing that the solid grounding given to the state elite in the course of their tertiary education would eventually spread – or ‘trickle down’ as we might put it today – to the rest of the population. A second aim of both approaches was to turn the pursuit of knowledge into a national endeavour, in other words, one in which the state should invest. The Napoleonic model is clear enough in this regard, but Humboldt’s model also shares this tendency, which he justified on the grounds that the university would contribute to the ‘moral training of the nation’. Perhaps Napoleon’s views might sound elitist to the contemporary ear, but Humboldt’s sound utterly bizarre. Perhaps they did to some of his contemporaries as well, especially since he went on to propose that the university be given an endowment and property to ensure its independence from the state and its freedom from political manoeuvring. A double bind, it would seem: on the one hand, the university as an institution whose work is claimed to be beneficial – indeed, essential – to the nation; on the other hand, the requirement that it be left to indulge in its pursuits unfettered, as long as the state honoured its duty to invest in it. We have travelled a long way since Humboldt’s time. I started with this episode in order to highlight the fact that contemporary debates – concerning the pursuit of knowledge (that is, research), the imparting of that knowledge (that is, pedagogy), and the relationship between these activities and society at large – are as old as the modern conception of the university itself. These debates have been gaining a new currency in recent years. In what follows, I would like to attempt to tease apart some aspects of these debates, with an eye on the local context. First, however, I need to make a disclaimer: This contribution should not be taken as a defence of the University as an ivory tower. There is an unfortunate tendency in the contemporary debates I referred to earlier, whereby any statement to the effect that the pursuit of knowledge should be allowed to proceed unhindered is taken to imply that academics are merely interested in a self-indulgent process of posing questions that have, at best, limited relevance to society, using procedures that do not hold up to scrutiny in the cold light of economic fact. I suspect we have all – lecturers and students alike – felt that we were the target of such views at some stage in our academic lives. I am probably not alone in occasionally succumbing to the tendency to lose patience with these views, but I suspect that this is the wrong reaction, not only because it appears high-handed in precisely the manner that constitutes one of the grounds for the accusation in the first place, but because a simple dismissal can never stand in for a proper explanation. We do owe our fellow members of society an explanation of what we do, articulated with clarity and humility. Nevertheless, it is interesting to observe how we are increasingly bringing academic work closer to the paradigms that have come to dominate our economic discourse. For example, some of us find ourselves seeking publication outlets first and foremost on the basis of their impact, much as a financial investment might be made on the basis of expected returns. Impact is also a central principle against which research funding proposals are evaluated, much as a company might use market research to inform its development of product lines. As for our tuition, we seek to justify our existence in terms of numbers of students, and to attract students on the grounds that the degree programmes we offer are, if not of a directly vocational nature, then at least passports that can take them places. In principle, I have no problem with any of these developments. If our design of degree programmes requires us to keep our fingers on our society’s pulse, so be it. If an attention to publication impact forces us to seek rigorous peer review before disseminating our work, so be it. And if impact assessments in our research funding proposals lead us to better public engagement, then so be it. A problem does arise, however, if in pursuing these and related practices, we lose sight of what a university is supposed to stand for. These practices become problematic when they result in an exclusively instrumental view of university education and research, a view that political considerations, often coming from outside the University itself, may find it desirable to promote. This is the main question that I am trying to address. In a nutshell: how can the role of the University as an institution engaged in the pursuit of knowledge be reconciled with its status as an economic asset? In one sense, of course, the answer is clear enough: University is said to ‘produce’ graduates, whose skills and knowledge percolate through social and economic structures, strengthening them in the process. I trust that the graduates who are gathered here this evening will have been irked by my use of the term ‘produces’. I dislike it intensely. The term is rooted in the instrumentalist view I am arguing against. It implicitly assumes a mechanical vision of tertiary education, somewhat akin to a production line which, when the machine is well-oiled and the line workers efficient, will assemble and disseminate useful objects. We all know how different, how far from the dynamic of a production line, the reality is. We do not produce graduates. We try to nurture intellects. Indeed, on a good day, we help intellects to nurture themselves and we learn from them as we go along. So much for the University’s role in the dissemination of knowledge and its social and economic contribution in this regard. The University’s other role – that of pursuing knowledge through research – is much trickier to justify. It’s usually here that ivory towers begin to be conjured up. Research doesn’t come cheap. Its outcomes are not always easy to quantify or immediately recognized as relevant. This is an issue that my colleagues in the humanities, in particular, are well accustomed to facing. But it is also a problem for the sciences. Would Alan Turing, in 2014, be able to acquire funding to pursue his research on one of the fundamental questions for pure mathematics that David Hilbert outlined at the end of the nineteenth century? Perhaps, but only if he were able to show that his account of computability and the resulting application to the decision problem could eventually serve as the basis for the machines that have completely changed our societies. I suspect that Turing, even in 1936, was aware of the potential impact of his abstract mathematical model. But that couldn’t have been his principal motivation – for one thing, it would take a few more decades – and much creative thinking in the field of engineering – before computing power could be feasibly harnessed. It seems to me that the tension I referred to earlier – between the knowledge-oriented roles of University and its status as an economic asset – is nowhere clearer than here, where research is concerned. It might also have become clear that, ultimately, this contribution is about money. I apologise for introducing this rather sordid note into this evening’s proceedings, but in my defence, even Humboldt, the humanist steeped in German idealism, was sufficiently realistic to see that his dream of an institution tasked with the pursuit of knowledge for the nation’s benefit could not come to fruition without factoring in the economics. So let me turn to the issue of research funding. Recently, I have noticed that my colleagues in institutions elsewhere have become increasingly prone to mourning the demise of funding models that support basic – or ‘blue sky’ – research, with public support becoming contingent on a prior demonstration that outcomes will directly translate into economic gains. Let me emphasise that I am talking here of national funding bodies. True, researchers in Europe, including Malta, have access to a significant amount of research funding from trans-national sources. However, national funding bodies continue to play a central role, for at least two reasons, one related to individual intellectual development, the other related to that old Humboldtian chestnut, what he referred to as the ‘moral training’ of the nation and what today, somewhat less grandly, we might refer to as our investment in the knowledge economy. Let me take the individual perspective first: To a starting researcher, fresh out of a Ph.D. or post-doctoral programme, national funding can be enormously beneficial in helping her to take the first steps towards consolidating her career, establishing a longterm research programme and building up a team of postgraduate and post-doctoral researchers. That is often the first rung on a career ladder that leads to larger-scale funding, once one’s research profile has been established and the necessary networks are in place. It is also important in ensuring that research is founded on a long-term vision, rather than being conducted piecemeal. One role of national funding bodies is to help researchers find a firm footing on that first rung, without constraining them too much by way of asking for their results to be translated into economic gains in the short term. That does usually begin to play a role when international or industrial funding is sought. But the whole point of the first rung is to prepare oneself for that. Call it an initial investment, if you will, one that promises to yield substantial returns over time. After all, one is usually in this for the long haul. What of the broader national or societal perspective? I think I’d be preaching to the choir if, here of all places, I indulged in a tribute to the value of ideas, of thinking out of the box, of inculcating – dare I say it? – a desire for knowledge for its own sake. I will however suggest that funding basic research is essential if we wish to nurture intellects as we are supposed to, if we wish to allow a rich public discourse to flourish, and if we wish to move beyond an instrumental model of tertiary education that views it as a one-way production system, or even as a graduate college, rather than a multi-party dialogue founded on the values of inquiry. Nor should the economic benefits be put aside: there can be no lasting economic benefit without proper investment in the foundations. I sense a possible counter-argument at this point, to the effect that such funding structures are already in place here. That is not entirely true, at least for science and technology, the field in which I myself work. The body that comes closest to the role of a funding council for scientific research in this country has recently launched a new Research and Innovation policy which is explicitly – and more or less exclusively – aimed at supporting commercialisation and knowledge transfer between academia and industry. In practice, access to research funds proceeds in stages, based on vouchers, to first ascertain the economic feasibility of an initiative. The potential for market penetration is a criterion that has to be satisfied prior to undertaking any research. On the face of it, this looks like an elegant solution – state funding would seem to be eminently justified if the criterion for its disbursement is a priori evidence that it will lead directly to a multiplier effect in the economy. One the other hand, one could turn the question on its head and ask why public funding should feed directly into private enterprise, but not, apparently, the other way round. One could also ask what the consequences of this model are likely to be. I have already hinted at some of them: Prioritisation of short- to medium-term applicability, at the expense of research addressing basic scientific questions, is only one of these, perhaps the most dire for the long-term economic picture. On a bad day – somewhat perversely, I admit – I envy those colleagues of mine in other universities who mourn the loss of funding structures that used to support basic research, not to the detriment of, but in addition to, industry-oriented knowledge transfer and applied work. I envy them because mourning a loss might be offset, if only partially, by the possession of a cherished memory. That seems preferable to the contemplation of a continuing absence. For that sums up the situation: A systematic programme of national funding for basic research remains absent, a yawning chasm between the reality on the ground and any goals we might harbour for developing centres of excellence. Perhaps the foregoing remarks strike an overly pessimistic chord. But that’s not the message I am trying to get across. I’m well aware that research is flourishing on this campus, some of it supported by the University’s own efforts at securing funds from external sources, based on a rather different kind of synergy between key economic players and academia than the one that seems to have been adopted by those tasked with designing a national vision for the future. Many ongoing research endeavours have been remarkably successful, not only in their impact on society at large, but in enriching the intellectual climate that is essential for the University to pursue its role effectively. Incidentally, the University’s own efforts at publicising its research, at making it visible and, in so doing, honouring its responsibility – our responsibility – to engage and communicate, have contributed in no small measure to my own awareness. So I would like to end on this note. There exist solid foundations that need to be built upon. Public support, financial and otherwise, is essential if this is to take place. This is a facet of our contemporary debate on tertiary education that cannot be properly tackled without the engagement of the individuals most directly involved. That includes most of the people gathered in this room, including the graduates whose achievements we are here to celebrate. We may have come a long way since Humboldt articulated his vision, but in another sense, we are not quite there yet.