Classical Studies Greek and Roman Views

advertisement

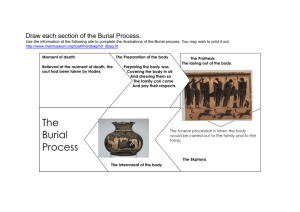

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT Classical Studies Greek and Roman Views on the Afterlife Support Notes [HIGHER] Edited by Richard Orr First published 1998 Electronic version 2001 © Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum 1998 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. ISBN 1 85955 142 4 Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY www.LTScotland.com CONTENTS Foreword v Section One Treatment of the dead Evidence from burial practices The trappings of burial Festivals of the dead Provision for the dead Dead men walking 1 Section Two The mythological underworld 5 Section Three The attitude of philosophers to the underworld and the afterlife 7 Section Four Alternative beliefs or lack of them 9 Section Five The mystery religions Eleusinian mysteries Bacchic mysteries Orphism Morality and good conduct Pythagoreanism Cybele Isis Mithras Christianity 11 Appendix 19 Bibliography 26 C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S iii iv C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S FOREWORD The material contained in this booklet is intended to open up some of the range of study areas available to the student who addresses Greek and Roman Views on the Afterlife as part of Religion and Belief in Classical Studies at Higher level. Sources are quoted extensively and further references are supplied in the Bibliography. The material provides a starting point for more extensive reading and is not intended as exhaustive: the topic is far-reaching and absorbing. While follow-up questions are not included, reference is made in the Bibliography to Units 3 and 4 (Mystery Religions and The Afterlife) of Religion and Belief - Starter Materials, available from Scottish CCC. These publications provide invaluable material for further study and demonstrate source-based questioning techniques which could readily be applied to this topic in seeking to satisfy the skills of knowledge and understanding, evaluating and practical analysis. R. Orr C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S v vi C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TR E A TM EN T O F TH E D EA D SECTION ONE Evidence from burial practices Burial customs and the cult of the dead provide some of our earliest evidence of human culture and in Greek and Roman times this evidence comes from archaeology as much as from written evidence. Burial practices and rituals in Greece and Rome are described in some detail in Domestic Religion in 5th Century Athens and in Domestic Religion in Rome in 1st Century BC and 1st Century AD, notes produced for Higher Classical Studies Religion and Belief (see Appendix). Our concern here is to determine what these practices and the treatment of the dead can tell us of the Greek and Roman views of life beyond the grave. The ancients were highly superstitious and their religion polytheistic with a wide range of gods and spirits. It would therefore not be surprising if beliefs in an afterlife and in ghosts of the dead were prevalent and indeed this was certainly so, with some notable exceptions especially among philosophers and thinkers. Death commands a feeling of awe by the very mystery which surrounds it and arouses many emotions in those affected by it. Some of its accompaniments are found in all periods and serve important functions. A public display of mourning and a ritual meal enable the heirs to the dead person to mask their feelings, be they release from a burden, grief or whatever other personal consequences and emotions follow on the death. Usually the burial rite itself serves to reinforce family identity, as does the setting up of an inscribed gravestone. Cremation and inhumation Chamber tombs had characterised the Mycenaean age although single burial in the Shaft Graves at Mycenae preceded the Beehive Chamber Tombs. Cremation was the practice in epic poetry, for example the treatment of the dead Patroclus in Homer’s Iliad 23 line 161ff, and the cremation of Misenus in Virgil’s Aeneid 6. Cremation was almost standard in Athens in the earlier burials found in the Cerameicus, the principal burial place outside Athens. However inhumation became commoner in the classical period although cremation still remained the more prevalent. Fashion, as well as considerations of space, materials and costs would have influenced the chosen method, then as today. Reasons of space and convenience no doubt determined that cremation was standard in Rome of the late Republic and in the early Empire but, in Hadrian’s time, inhumation was again on the increase and Christianity gave inhumation a further boost. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 1 TR E A TM EN T O F TH E D EA D The trappings of burial Gifts appropriate to wealth and status are made to the dead person. Women may be accompanied in death by their jewellery, clothing, perfume containers and other items regularly used by them in life. Men will have their weapons, work tools and other items treasured in their lifetime, while children may have toys. It is noteworthy that for the Athenians from Solon’s time on (594/593 BC), legislation specifically restricted expenditure on funerals and the amount of grave goods to be buried. Thus regulations on stone at Delphi dating to around the Fourth Century BC state: Not more than 35 drachmas’ worth of grave goods may be put in the grave, whether these grave goods are specially bought or taken from the home. If this regulation is broken, a 50-drachma fine will be enforced. Such rites as those for Patroclus in Iliad 23 or for Misenus in Aeneid 6 are reserved for heroes and represent special situations. In the case of Patroclus, sheep and cattle, four horses, two pet dogs and twelve Trojans were burned on the pyre. The gravestone or stele to mark the burial was again suited to the wealth and status of the deceased and became the centre of family ritual. On the third and ninth day following the death, the Athenian custom was to offer food at the grave while on the thirtieth day a funerary banquet at the graveside concluded the period of mourning. I, his adopted son, cared for Menekles while he was alive. When he died I buried him in a manner appropriate both to him and to me and set up a fine memorial to him. I carried out at his tomb the ceremonies to his memory and all the other necessary rituals on the ninth day. [Isaeus 2.36, On the Estate of Menekles] Festivals of the dead The offerings made to the dead, especially the provision of food, wine and oil imply a belief that the deceased would require further support in the afterlife and that goodwill had to be secured. This belief is reinforced when we consider Greek and Roman festivals which related specifically to the dead. The Athenians had certain days assigned to the dead which were known as the Nekysia and also the Genesia, an ancient festival commemorating the birthdays of the family’s dead ancestors. On these days, graves would be decorated with wreaths and ribbons and special offerings were made at the tomb. Milk, honey, water and wine are all specified. In the Persae, lines 611-618, Aeschylus lists the offerings being made to the gods below and to the ghost of the dead Darius as ‘pleasing white milk from a hallowed cow, clear honey, spring water, refreshing juice from an ancient vine, fragrant olive oil and wreaths of flowers’. Flowers and other gifts were also possible at the grave. Better known to us is the three-day festival of the Anthesteria, a flower festival to Dionysus. On the third 2 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TR E A TM EN T O F TH E D EA D day of this festival, mixed vegetables and cereals were offered to Hermes, the guide of the dead, and it was believed that the dead roamed freely among the living. Precautions were taken to keep the ghosts at a distance, such as smearing doorways with pitch. When the day was over, the cry went up calling on the dead to go back whence they came as the festival was at an end. A full account of this festival appears in Burkert, pp. 237ff and a shorter account appears in Zaidman, p. 77. For the Roman Parentalia commemorating dead relatives and the Lemuria when the spirits of the dead were thought to roam freely, and had to be placated, see Domestic Religion in Rome in 1st Century BC and 1st Century AD, pp. 15-16 (and reproduced in the Appendix to this booklet). Provision for the dead Belief in a life continuing within the tomb helps to explain the gifts and grave goods and the occasional supply of food over the years. Large tombs in Roman times might even include a dining room for the graveside banquet. Petronius in his Satyricon (71) makes a wealthy freedman Trimalchio go into great and exaggerated detail as he provides for his own tomb ‘to secure a life after death’. He proceeds The tomb should have a frontage of 100 feet and a depth of 200 feet; for I want to have every kind of apple and grapes in profusion growing around my ashes. It is a serious mistake for someone to have a fine house while he is alive and yet to have no thought for the home where we will have a much longer stay. Trimalchio sets out the details of the inscription for the tomb, asks for a dining table to be included and below his statue wishes to have displayed his little dog, wreaths and perfume and a list of the fights of his favourite gladiator! The common inscription found in Roman tombs after First Century BC as well as in Imperial times ‘sit terra tibi levis’ (abbreviated to STTL) ‘may the earth lie light upon you’ has also a significance for the idea of the continuing life of the deceased in his grave. Many inscriptions reinforce the belief. Here is my eternal home, here my dwelling place and here I shall be for all time. Dead men walking All this concern over the afterlife of the dead and the existence of festivals for the dead encouraged a belief in ghosts and sightings of ghosts. So the ghost of Darius appears on stage in the Persae of Aeschylus (line 681ff), and Plautus’ play Mostellaria takes its name from a supposedly haunted house. In the Phaedo, Plato suggests that on death the soul is not immediately freed from its body parts and remains visible as a ghost. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 3 TR E A TM EN T O F TH E D EA D We must imagine that the body parts are heavy, earthly and visible and that, as the soul still has some part of these, it is weighed down and dragged back to the visible world, flitting around monuments and tombs, where such shadowy phantoms of souls are seen. [Phaedo, 81CD] Horace casts a curse at witches When my time has come and I die, I shall come on you in the night as a Fury. My ghost shall attack your face with crooked talons - such is the power of the ghosts of the dead. I shall sit firmly in your restless heart and banish sleep through fear. [Horace, Epodes, 5.91-96] Pliny tells of a ghost which haunted a house in Athens and drove its tenants to death, such was their terror. The philosopher Athenodorus eventually met the ghost and laid it to rest by giving it proper burial. In the silence of the night, a noise of metal was heard and if you listened more carefully there came the rattling of chains, first at a distance and then nearby. Soon there appeared the ghost of an old man in a terrible state of decay and dirt, with flowing beard and rough hair. On his legs he had shackles, on his hands chains and these he shook about. Athenodorus followed the ghost and marked the spot where it had disappeared. The place was dug next day and bones were found. The bones were collected and given public burial. From then on the house was freed of its ghost which had received proper burial. [Pliny, Letters, 7.27] In the Twelve Caesars, Suetonius tells a similar tale. After his murder, the Emperor Gaius Caligula was secretly taken to the Lamian Gardens and given incomplete burial. From that time the gardens were haunted by his ghost until his sisters at last exhumed his body and put it in a tomb. [Suetonius, Gaius, 59] Ovid’s Fasti has reports on the discontinuation of the celebration of the Parentalia at a time of extended warfare. This act did not go without punishment. It is said that the spirits of the dead left their tombs and moaned through the silent night. Through city streets and countryside, insubstantial ghosts flocked, howling and shrieking. As a result of this, the former rites were resumed at the tombs of the dead. 4 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E M Y TH O LO G IC A L UN D ER WO R L D SECTION TWO Alongside the personal cult of the dead was the mythological world described most fully in epic poetry. This was the world of Hades and his Queen Persephone, the site of Tartarus for sinners and Elysium for heroes, where Cerberus the three-headed dog stood guard and the rivers Styx, Acheron and Phlegethon flowed, with Charon ferrying the dead souls. Homer’s Odyssey Book 11 and Virgil’s Aeneid Book 6 are the key passages for study here. Of course there were many inconsistencies of detail in the various accounts of the Underworld at different periods - so Elysium is placed by Virgil in the actual Underworld in Aeneid 6 while in Homer’s Odyssey it is found at the end of the earth. The gods will send you, Menelaus, to the Elysian plain at the ends of the earth where man’s life is far the easiest and there is no snow, nor stormy weather nor rain. [Homer, Odyssey, 4.563-566] Again for Homer in Odyssey 11, the ghosts of the dead are mere shadows and can acquire consciousness and power of speech only through drinking blood. There is no such requirement set by Virgil in Book 6. Homer emphasises that the Underworld is altogether a hateful place with no attraction for man or god. When the gods join in the fighting at Troy in Iliad 20.62-65 we are told: Hades, the King of the Dead, jumped up from his throne and shouted out in fear lest the earth shaker Poseidon would tear open the earth above him and the dreadful decaying abode of the dead would be revealed to man and god alike, a place hated even by the gods. It was here that the Erinyes or Furies were to be found punishing the dead for perjury or for other misdeeds on earth. So in Iliad 3.278 where Agamemnon appeals to ‘the Erinyes who punish in the world below any man who takes a false oath’. Sin is certainly punished and there is a moral aspect in the Underworld. So it is in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, lines 367-369. Persephone, Queen in the Underworld, has power to punish evil doers for all eternity. It also suggests that the dead have some consciousness despite the picture of gibbering C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 5 TH E M Y TH O LO G IC A L UN D ER WO R L D shadows with no consciousness which Homer presents in Odyssey 11. The question to be asked is how far this picture of the Underworld was actually believed by the ancient Greeks and Romans and there is room here for debate. 6 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E A T TI T UD E O F P H I LO SO P H E RS T O T H E UN D ER WO R LD A ND TH E AF T ER L IF E SECTION THREE As early as the Sixth Century BC, philosophical thinkers were questioning established beliefs. If Homeric gods were not evident and visible, why should they be accepted? Anaximander of Miletus in Ionia explained the universe with no reference at all to Zeus or Apollo. Xenophanes of Colophon, again in Ionia, attacked polytheism and a belief in anthropomorphic gods. He further deplored the immortality attributed by Homer to the gods. There were many other great thinkers but their influence on general thought appears to have been slight. Next to attack traditional religious belief came the Sophists in Athens. Most prominent here was the statement of Protagoras of Abdera who commented when writing On Gods. As for the gods, I cannot say that they are or that they are not... for there is much which stops us from knowing, such as lack of clarity about the subject and the shortness of human life. This certainly caught public attention and Protagoras was put on trial and made to flee from Athens. His book was publicly burned. When Democritus of Abdera propounded his atomic theory in the Fifth Century BC, he provided Epicurus of Samos with a means to attack superstitious belief and fear of the gods and death. Alongside this, philosophers recognised an eternal element in the universe and with this the human soul or psyche came to be identified and this in turn led to the belief in the immortality of the soul. This brings us on to Plato, the first philosopher whose works survive in their entirety and whose teachings on the nature of the soul have been so influential. Plato regards the soul as immortal and sees its goal as complete understanding gained by viewing the form of truth and beauty: Mind guides the soul to a view of true reality which nourishes and benefits the soul. [Plato, Phaedrus, 247CD] Stoic philosophers saw the soul as a particle of divine fire to which it returned after death and so retained its immortality. Yet despite all these philosophical teachings, we can be sure that the majority of ordinary Greeks and Romans were too superstitious to dismiss the idea of the Underworld and took seriously the possibility of life beyond the grave. Some of the Greek thinkers mentioned above questioned belief in the gods and the whole fabric of the Underworld; most offered some alternative suggestion. Roman writers on the C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 7 TH E A T TI T UD E O F P H I LO SO P H E RS T O T H E UN D ER WO R LD A ND TH E AF T ER L IF E other hand tend to be critical but less likely to offer an alternative philosophy. The writer Lucretius tried to free Romans from their fears by expounding the beliefs of Epicurus when he wrote his De Rerum Natura and declared that the atomic composition of the universe denied any place for the gods and the bogeys imagined in the Underworld. But Lucretius’ writing fell largely on deaf ears, so that educated Romans continued to speak dismissively of fears of the Underworld, clearly implying a continuing belief at all levels of society. The fear of Acheron must be driven out headlong, a fear which disturbs human life from its very depths and covers everything with the blackness of death. [Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, 3.37-40] In his Tusculan Disputations, Cicero also dismisses the terrors of death and the mythological Underworld and goes on to attack philosophers like Lucretius and his tutor Epicurus. I often wonder at the extremes of some philosophers who marvel at natural science and in their excitement offer thanks to its proponent and discoverer, worshipping him like a god; for they say that he has freed them from grim masters, perpetual terror and fear by day and night. What terror? What fear? [Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, 1.21.48] Juvenal also attacks the myth. Not even a child believes that there are ghosts and realms below the earth and a punt pole plying among black frogs in the Stygian river and so many thousands crossing in a single boat. [Juvenal, Satires, 2 149-152] Lucretius also denies the soul any immortality. As mist and smoke disperse into the air, you can be certain that the soul also is dispersed and perishes much more quickly, breaking up into its original atoms. [Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, 3 436-438] As we move on from the mythological picture of the Underworld, it is perhaps appropriate to note how far the Christian picture of Hell draws on pagan belief. The whole question of how the good and the bad are given different treatment continues from ancient times until today. 8 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S AL T E RN A T IV E B E L I EF S O R LA CK O F TH EM SECTION FOUR Superstition ensured that most Greeks and Romans gave credence to the stories about the Underworld and its gods and little impact was made on the public at large by the teaching of the philosophers. Yet there were many Greeks and Romans who feared that there was nothing beyond the tomb and this could certainly lead to an appearance of hopelessness. Thus: Suns can set and rise again: but once our brief light dies, everlasting sleep awaits us. [Catullus, 5.2] A First-Century BC tombstone inscription from Spain reads: Hail! Herennia Crocine, beloved of her own family, is shut in this tomb. My life is spent; other girls too have lived out their lives and died before me. So enough now. May the reader say as he goes ‘Crocine, may the earth rest lightly on you’. Farewell to all of you on the earth above. Cicero shows a swing in his mood in a letter to his friend Atticus. I am more troubled by that long time when I shall not exist than by this life which, brief though it may be, yet seems to me to be too long. [Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 12.18.1] Horace says: Once we die and go where good Aeneas, wealthy Tullus and Ancus have gone, we are but dust and shadow. [Horace, Odes, 4.7.15-17] Seneca is recovering from a bad bout of asthma and says: Does death often test me? Let it do so. I experienced it long ago. When? Before I was born. Death is merely non existence, not being alive. I already know what that feels like. [Seneca, Letters, 54.4] However, many educated Romans still harboured hope of immortality through fame. Indeed, even the philosopher Epicurus while denying immortality to the soul, requested in his will that his own birthday be celebrated monthly! C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 9 AL T E RN A T IV E B E L I EF S O R LA CK O F TH EM Thus Cicero says: Yet if the soul had no hint of a future existence and was confined within life’s bounds, it would not break itself with such toil and effort and put its very existence at risk. But deep in every good man there resides a quality which demands that the memory of our name should not end with our life but be extended across eternity. [Cicero, Pro Archia, 11.29] Again Horace has this to say on the impact of his poetry. I have set up a monument more lasting than bronze and mightier than the pyramids which neither wind nor rain can destroy nor the passage of endless time. I shall not altogether die - a great part of me will avoid the goddess of death. [Horace, Odes, 3.30.1-7] The multitude of dedications and inscriptions, be it on tomb or public building, is another effort to ensure some memory of the dead remaining after he/she goes. 10 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO NS SECTION FIVE For many, a much more hopeful alternative belief was to be found in initiation into one of several mystery religions which were accessible to all and indeed did not debar the initiate from participating in traditional state religion. The Mysteries originated in Greece and mostly were of Eastern origin. Their common features were a ritual of purification which the initiate must undergo, communion with the god or goddess, and the promise of happiness beyond the grave. The actual rite of initiation was secret. Eleusinian mysteries These began in the Sixth Century BC and most adult Athenians, including slaves and women, participated as they took place so near to the city. Initiation extended over a six-month period. Sacrifice and ritual bathing were followed by a procession to Eleusis where the initiate underwent an experience in a dark torch-lit area and objects associated with the Mysteries were revealed in a brilliantly lit setting. The ear of wheat and fertility symbols would be among these objects as appropriate for an agrarian cult connected with Demeter and the rape of her daughter Proserpina by Hades. Indeed, perhaps this was enacted by a drama. Such a drama might well have depicted Hades’ seizure of Proserpina to become his queen in the Underworld; the extended search by Demeter, with torches to assist her in the night and the death of the crops owing to her lack of attention; the discovery of Proserpina in the Underworld; their agreement that she should share her time with Demeter on earth and with Hades in the Underworld; the impact of this on the rebirth and growth of crops when Proserpina was with Demeter and their corresponding death during the time that she spent below the earth - so was the celebration of summer and winter, sowing and reaping, birth and death combined in story and as a visible reality. Growth, cutting back and future growth again from the cut corn ears was part of the symbolic message. Death results in renewal and there is a better fate assured in an afterlife. The Emperor Augustus patronised Eleusis and the Mysteries had a long life at that particular centre. This is written of the Eleusinian Mysteries: Happy among mortals is the man who has seen these things: but he that is uninitiated in the sacred rites and has not participated has no such happy fate when he is gripped by gloomy death. [Homeric, Hymn to Demeter, 480-482] C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 11 TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S Again Pindar says of the Eleusinian Mysteries: Blessed is the man who sees these mysteries before going down into the hollow earth. He knows how life ends and knows too the beginning granted by the gods. [Pindar, Fragments] The Apostle John may have the Eleusinian rite in mind at 12.24: Unless an ear of corn falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies it brings forth fruit. For a fuller description see Zaidman, page 132ff and Burkert, page 276-8 and also page 285ff. Bacchic mysteries The Mysteries of the god Dionysus or Bacchus differ in that they were not tied to any one sanctuary but could be celebrated wherever worshippers came together. Bacchic Mysteries were open to male or female adults and involved frenzied possession by the god. Wine was drunk and sexual acts performed in the course of this surrender to the power of the god. The eating of raw flesh too was associated with the frenzy of the Bacchants, as the worshippers were known. Euripides’ Bacchae is an important source of evidence for this cult and its activities when King Pentheus tried to spy on his wife and her frenzied company and was torn to pieces for his efforts. As with the Eleusinian Mysteries, initiation brought blessings in the afterlife: Blessed is he who knows the initiation of the gods and lives a pure life and introduces his soul into Bacchic revels. [Euripides, Bacchae, 72-77] Plato in his Phaedrus comments: ‘The greatest of blessings come to us through godinspired madness’ (244A). Later Plato identified the mystic madness of Dionysus as one such blessing (Phaedrus, 265B). The Bacchic celebrations later became identified with orgies in Rome so that in 186 BC the Romans suppressed the Bacchanalia and banned them as being both political and pernicious. Livy 39.8-19 describes the incident at some length. (See Shelton, page 396.) Some of the rites of Bacchic initiation are depicted in the striking wall paintings which appear in the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii, which shows incidentally that the rites survived into the First Century AD (for a description, see Ferguson pp 102-104). Bacchic Mysteries became associated with the mysteries of the Pythagoreans and 12 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S some aspects of Orphism. Herodotus (2.81) suggests a ritual, ascribed to the Orphic or Bacchic cult, is in fact Egyptian or Pythagorean. The confusion and inter-relation among these three Greek Mystery cults is thus intensified and it is difficult to separate them. Orphism Orpheus was a legendary figure dating to the story of the Argonauts, who attempted to recover his wife Eurydice from the clutches of Hades. The story is told in Virgil’s Georgics 4.453ff. Orpheus died when torn to pieces by frenzied female Bacchants - an obvious link here with Dionysus. Orphism developed its own cosmogony and had its own story of how the young Dionysus was torn apart by the Titans before being boiled, roasted and eaten by them. Only his heart was saved and this enabled his re-creation. Here again there is a reference to the eating of flesh and a link with Bacchic Mysteries. Significantly however Orphism banned the killing of animals, the roasting of anything which had been boiled and the eating of flesh. Plato was influenced by Orphic thinking but attacked wandering priests who read from Orphic books and offered purification through initiation (Plato, Republic, 2.364B - 365A). Morality and good conduct Initiation into the Mysteries was not in itself sufficient to secure the future welfare of the soul - good conduct was also a requirement. In epic poetry there was different treatment meted out to the good in Elysium and to the wicked in Tartarus and we have seen the role of the Erinyes in punishing the wicked. Pindar in various fragmentary texts tells of the soul’s survival and its link with the divine. Elsewhere he adds that if it has committed sin, it must first undergo purification. Similarly: If a man who has means knows the future, he knows that the lawless spirits are punished when they die... but the good have an untroubled life... among the honoured gods.... [Pindar, Olympian Ode, 2.55-72] From Pindar on, the link of the soul with the divine, and its immortality, and the impediments on its progress towards true blessedness, all become a major concern for philosophers. So Orphism adopted the idea of punishment for the wicked and recognised that initiation into the Mysteries and goodness would secure eternal blessedness. Plato developed these beliefs in the Phaedrus at some length. Note particularly: C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 13 TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S In all these states [of the soul in its passage towards blessedness] the man who lives justly enjoys a better fate and the man who lives unjustly suffers a worse one. [Plato, Phaedrus, 248E] Again in the Phaedo, Socrates embarks on a marvellous story of the immortal soul’s fate after death, incorporating many features of the mythological Underworld and concludes: Because of this, a man should be confident about his soul if he has kept clear of pleasures and ornaments of the body as being likely to do him harm and rather has pursued learning and equipped his soul with wisdom, justice, courage, freedom and truth. [Plato, Phaedo, 63E] Cicero follows much of Plato’s teaching in his Tusculan Disputations and Christianity also continues to emphasise that morality matters and wickedness is punished. The areas of overlap between the Bacchic Mysteries and Orphism led to conflict between the two cults. Orphism later became misused and fell from favour despite the high points of some aspects of its doctrine which made their mark on Plato’s thinking. Pythagoreanism The Pythagorean School originated with the Sixth-Century philosopher and scientist Pythagoras who lived in South Italy. Ovid provides a lengthy account of his life and teachings in his Metamorphoses 15.60ff. Here again, as with Orphism, we find the Pythagoreans debarred from eating flesh and a strong belief in the transmigration of the soul after death (also known as Metempsychosis). This belief was central to Pythagorean thinking and reinforced the belief in the soul’s immortality. Herodotus knew of this doctrine of transmigration: The Egyptians were first to declare that the human soul was immortal and passed at the death of the body into another living creature which was being born. After passing through all the creatures in land, sea and air, over a threethousand-year period, it again enters a human body at birth. [(Herodotus, 2.123] Transmigration was taken up by Orphism and from one of the two, either Pythagoreans or Orphism, Plato took up the theme. He describes a view of it in the long story of Er in Republic 10.614B ff. Virgil alludes to transmigration in Aeneid 6.713. When Aeneas asks about the identity of spirits crowding the river bank he is told: 14 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S These are spirits to whom a second body is owed to Fate. At the river Lethe they drink water which removes all care and brings long forgetfulness. In his Letters 108.19, Seneca says: Pythagoras says that all things were inter-related and that there was a constant flow of souls passing over into different forms. If you believe him, no soul ceases to exist and there is only the shortest pause while it is transferring into another body. Pythagoreanism was less of a cult than the Mysteries of Eleusis, Bacchus or Orpheus and was rather a religious way of life. It shared some of the teaching of the Mysteries and certainly influenced Plato’s thinking, but it made less general impact. Cybele Other Mystery religions existed and came to have significant influence in Rome. Both Isis and Cybele, the Eastern goddesses, were prominent and Apuleius tells much of the rituals of Isis in his Golden Ass. (See Shelton, p. 403.) Cybele, the great mother goddess from Anatolia, was a goddess of fertility. She was associated in her worship with Attis, her young lover who castrated himself and bled to death, only to be reborn. Her priests were eunuchs. Worship of Cybele came to Rome in 204 BC, in obedience to a prophecy, and games known as the Megalesia were instituted. The historian Livy provides a full account in his History Book 29.1014. (See Shelton, pp. 401-3.) The Romans disapproved of the castration involved in her rituals and the worship of the goddess was firmly controlled. Roman citizens were expressly forbidden to participate. However in Claudius’ reign in the First Century AD, her priesthood was opened up to Roman citizens and the restrictions removed. Her cult involved fasting and purification, ritual purification by bathing in the blood of a bull or ram and a belief in immortality. Isis Isis was the other great mother goddess from the East but her main origins lay in Egypt. She was sister and wife of the divine Osiris who was murdered and dismembered by his brother. Like Demeter, Isis roamed the world in search of Osiris and ultimately, with the help of Anubis, the dog-headed god of the dead, Osiris was resurrected to become king of the dead. Isis was associated with the land and Osiris with the corn and its fertilisation by the River Nile. The Greeks, not surprisingly, associated this cult of Isis with their own Mysteries at Eleusis. Worship of Isis spread across the Mediterranean to Pompeii and then Rome where she was very popular with C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 15 TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S the poorer classes. Temples were built to her, particularly in the time of the Empire. Her Mysteries were of great significance in Rome. Her priests shaved their heads and her processions through Rome’s streets were noisy and striking occasions. Initiation rites were, as always, secret but involved a ritual death and a vision followed by Epiphany or revelation to the people. In The Golden Ass, Apuleius describes her rites, the procession and initiation at considerable length. Juvenal comments: Highest honour goes to [the priest impersonating] Anubis who, with his linen-clad, shaven-headed followers, mocks the people as they weep. [Juvenal, 6.532] Pausanias also comments: The Egyptians have a festival of Isis at the time they say she is lamenting Osiris; at that time, the River Nile begins to rise and many say that the tears of Isis are causing the river to rise and to water the ploughed land. [Pausanias, 10.32.10] Mithras Also of great importance to the Romans was the worship of Mithras. He originated in India and was associated with the sun and light. He became connected with the Persian god Ahuramazda. His Mysteries came to the fore in the First Century AD and he was particularly worshipped by soldiers. Mithras was said to have had a miraculous birth from a rock and was revered by shepherds. His date of birth was celebrated on 25 December. He had two great exploits, a trial of strength with the sun god which resulted in their alliance, and the capture and killing of a bull. The chapels of his worship which have been discovered throughout the Empire were darkened and cave-like and contained a relief of Mithras killing the bull. Only men were permitted to participate and initiates had to pass through seven grades or tests of endurance. There was a communion feast at the conclusion, with the drinking of wine. Mithraism related to the passage of the soul through life and its trial in the fight between light and darkness, good and evil, life and death. Despite its great popularity with the army, Mithraism made little impact on the civilian population of Rome. Christianity Christianity made headway with the poorer classes in Rome. Those in authority viewed its practices with suspicion, and its intolerance of other religions was a serious 16 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S problem. Christianity was probably never expressly forbidden but was certainly viewed as a threat to public order - obstinate refusal to comply with public sacrifice expected of Roman citizens inevitably brought punishment. This is well shown in a correspondence between Pliny and the Emperor Trajan in Pliny’s Letters 10.96 and 97. Pliny discusses the treatment of Christians and considers their worship. (See Shelton, p. 414.) The Mystery Religions prepared the way for Christianity. Despite its own intolerance of other religions, Christianity absorbed various practices from the rival mysteries, and pagan festivals and gods were taken over as Christian festivals and saints. Belief in a life hereafter was central to Christian doctrine. The debt of Christianity to religions which preceded it provides a fascinating study in itself, as we review the wider issue of man’s attitude to life after death. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 17 TH E M YS T E RY R E L I G IO N S 18 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S APPENDIX The following texts are quoted by permission from Higher Classical Studies - Religion and Belief - Domestic Religion in Fifth-Century Athens and Domestic Religion in Rome in First Century BC and AD, both by Maureen Cooke (Central Regional Council, 1995). Death and burial in Athens There were many traditional observances connected with death and burial. When someone died, a three-day period of fasting began and a cypress branch or lock of hair was hung on the door of the house to tell people that a death had taken place. A bowl of water brought from outside the house was placed outside the door. This water was for visitors to purify themselves as they left the house. The eyes and mouth of the dead person were closed by the nearest relative. Then the body was washed in water brought from outside and clothed by the women of the house. The body was usually dressed in a white shroud or ankle-length robe. It was common to put a crown on the head, sometimes of gold, sometimes of parsley. A dead woman wore her jewellery and her hair was arranged as it had been in life. Young people who died unmarried and the recently married were buried in wedding clothes. We know that by the late Fifth Century BC it had become the custom to provide the dead with a small coin, usually an obol, in the belief that it was necessary to pay Charon, the ferryman of the dead to take the soul across the river Styx into the underworld. Aristophanes gives evidence of this custom in a comedy performed at Athens in 405 BC. In the play, Charon has just taken the god Dionysus across the river Styx and now demands the fare. Charon: Stop, stop, take the oar and push the boat in. Now pay your fare and go. Dionysus: Here, take it - two obols. [Aristophanes, Frogs, 269-270] However no coins have been discovered at Athens in graves earlier than the Fourth Century BC which perhaps suggests that the custom was not widespread at Athens during the Fifth Century but became more common during the next century. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 19 APP EN D IX The body, with the feet towards the door, was placed on a bier covered with a cloth, usually in a checked pattern if the evidence of the vase paintings is correct. A cushion was placed under the head. Around the bier they placed branches and lekythoi, the characteristically shaped jars for oil which were used in the funeral ritual; they also decorated the walls with wide ribbons. Now on the couch scatter bitter herbs, break off four vine-branches and place them beneath; beside the couch set oil jars, fasten the ribbons and place the water pot at the door. [Aristophanes, The Assembly Women, 1030-1033 (Fifth Century BC)] Mourners stood around the bier or sat on low stools. The mourners sang laments and sometimes professional mourners were employed to do this. The relations of the deceased made extravagant gestures of grief, tearing their cheeks and hair and beating their breasts. ... cries of grief, wailing of women, tears and beating of breasts, torn hair and blood-stained cheeks. Perhaps too, dust sprinkled in the hair and clothes are rent. [Lucian, On Funerals, 12 (Second Century AD)] The singing of set dirges and extravagant gestures of mourning had been forbidden by law during the Sixth Century BC (Plutarch, Life of Solon, 21, 4). However evidence suggests that the law did not entirely succeed in preventing these practices. Men made a farewell gesture with hands outstretched and called three times upon the dead. (Scholiast on Euripides, Alcestis, 98-100) This part of the funeral ritual lasted for twenty-four hours. The burial Before sunrise on the following day the funeral procession took place. Sometimes the body was carried to the burial ground in a hearse pulled by mules or horses but more often by hired pall-bearers. A man walked in front of the body and women followed behind. Only women who were closely related or over 60 years of age could attend. The procession was accompanied by flute players. When they reached the burial ground, the coffin was sealed and an offering of wine was made to the dead. The body might be buried or cremated, burial being the more common during the Fifth Century. If the body was cremated, the fire was put out with wine. The nearest male 20 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S APP EN D IX relative gathered the ashes and placed them in an urn. The funeral meal After the burial, the relatives returned to the house where they shared a meal. This ended the three-day period of fasting. Speeches were made in praise of the person who had died. Visits to the tomb Visits to the tomb were an important part of the funeral ceremonies and were made on the third, ninth and thirtieth days after death. Very little is known about these visits but we do know that various offerings were made, lekythoi containing olive oil, honey, cakes, eggs, pomegranates and drink offerings. Drink offerings consisted of honey, milk, water, wine and oil, either one of these or two or more mixed together. The person making the offering first prayed to the dead person and then poured the offering at the foot of the stele. While he did this, the other members of the family sang dirges. Afterwards they often smashed the jugs which had contained the offering. Visits were also made to the tomb throughout the year, particularly at the festival of Genesia, an annual state festival of mourning. Lekythoi show tombs decorated with wide ribbons, blue, green, purple, black and red, women bringing offerings in flat baskets and making libation at the grave. One shows a lyre and discus, perhaps denoting the particular skills of the dead person; another shows a sword, possibly indicating that it was the tomb of a man who had died in battle. Greenery and flowers were also used. ... we are accustomed to decorate the tombs of the dead with parsley. [Plutarch, Life of Timoleon, 26, 2 (Second Century AD)] Graves might be marked by a column or a stele, an upright stone tablet. Tombstones laid flat on the ground were also found. Stepping on a tombstone was regarded as a cause of pollution. He will not step on a tombstone or go near a dead body or a woman who has just given birth, saying that he must avoid defilement. [Theophrastus, Characters, 16, 20-22 (Fourth Century BC)] Sometimes an inscription warned against any interference or defilement of a grave. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 21 APP EN D IX If anyone shall rob this grave of its ornaments, or open it, or disturb it in any way, may he never walk the earth nor sail the sea but be destroyed with all his race. [Boeckh, Greek Inscriptions, 916] Many of the Athenian beliefs and customs surrounding death were shared by other Greek states. A number of these customs have survived with little change into modern or relatively modern times, particularly in rural areas. It is still customary in many places for the body to be prepared for burial by the women of the family. The body is washed with water brought from outside the house and dressed in new clothes. As was the custom in Fifth Century Athens, the young or newly married may be dressed in wedding clothes. The body is often still placed with feet towards the door. The ancient Athenian custom of decorating the bier with herbs such as marjoram and basil to ward off evil influences and evergreen as a symbol of some sort of survival after death still persists. The practice of providing the deceased with a coin has not entirely died out. The coin is placed on the forehead or mouth as a charm against evil influences although one folk song describes it as ‘Charos’ fee to take the soul across the river of death’ - a reminder of the ancient belief. The singing of both set and improvised laments for the dead is still very important. The laments are sung by the kinswomen and others who have known the deceased and by professional mourners just as happened in Athens before Solon’s legislation banned the singing of set dirges, legislation which seems frequently to have been disregarded. In some areas the ancient gestures of grief can still be seen, women beating their breasts, rending their cheeks and tearing at their loosened hair or black head-scarves. In Epirus the nearest male relative of the deceased still holds out his right hand as a gesture of farewell, the ancient gesture having become part of the Christian burial service. Visits to the grave take place on the third, ninth and fortieth days after death and on each anniversary, an obvious survival of Athenian custom. Offerings of wine and water are placed at the grave and improvised laments are sung. In many places it is still customary to purify the house after a death, cleaning it thoroughly, white-washing the walls and throwing away any water standing in containers. 22 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S APP EN D IX Death in Rome When a death took place, the household was in a state of taboo and observed a period of mourning, which lasted until eight days after burial. The deceased person was washed, anointed and dressed in his best clothes. Burial took place almost immediately, the essential thing being that the body should be put under earth. The form which the funeral took depended on the status of the family; from Horace we hear of bodies being disposed of unceremoniously. (Horace, Satires, 1.8.8-16). Before being taken from the house the body was purified by the offer of a sacrifice to the Lares. A funeral possession was accompanied by torches, fire and light both being thought to provide protection against bad luck and evil influences. The relatives, including the children, followed the bier. A pig was sometimes sacrificed to Ceres as the goddess of the earth to whom the dead returned. Cremation was common but not universal. If the body was to be cremated, the next of kin lit the fire, his face turned away - a common precaution in religious rites where evil influences might be present. The rites described above were the rites of the early Romans but important and wealthy families adopted some of the elaborate practices of the Etruscans. We hear of elaborate processions with musicians, professional mourners, and actors wearing funeral masks to impersonate the ancestors of the dead. At a suitable place, for example, the Roman Forum, the funeral procession would stop and a speech would be made in praise of the deceased. The principal religious element in the ceremonies connected with death was the purification of the living from any contamination which they might have suffered. This comprised a sacrifice to the Lares, the sweeping of the house and the rite of suffitio where the members of the family were sprinkled with water and had to step over fire. The ninth day after the death marked the end of the normal period of mourning. Sacrifice was offered followed by a solemn meal. In February each year a festival was organised by the State during which each family mourned the family dead. This was known as the Parentalia - the Festival of All Souls. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 23 APP EN D IX Appease the souls of your ancestors and bring little gifts to the extinguished pyres. Their ghosts seek little; piety is more pleasing than costly offering. A tile wreathed with garlands, some sprinkled corn, a little salt, bread soaked in wine and a few loose violets are offerings enough. Place these on a potsherd left in the middle of the road. Not that I forbid greater offerings, but the shades are pleased with these. Add prayers and the appropriate words at the hearths set up for these rites. [Ovid, Fasti, 2. 533-542 (early First Century AD)] The Lemuria The Lemuria took place on 2, 11 and 13 May. The origin of the Lemuria was a belief that the spirits of the dead who had not received proper burial might return to their former homes at this time. It bears a striking resemblance to the third day of the Anthesteria at Athens. ... at which times in the sacred rites they throw a bean by night and say that they cast out the ghostly folk (lemures) from their homes. [Varro quoted by Nonnus Marcellinus (Third Century AD)] The only other useful source is Ovid who, fortunately for our purpose, describes the rite in some detail. At midnight when the night lends silence to sleep, when dogs and brightly coloured birds are hushed, he who is mindful of the ancient rite and fearful of the gods arises; no sandals on his feet, he makes a sign with thumb in the middle of his closed fingers lest an insubstantial shade should meet him in the silence. When he has washed his hands, purifying them in running water, he receives black beans and throws them from him with face averted. But as he throws them he says, ‘These beans I cast; with these beans I redeem me and mine.’ This he says nine times without looking behind him; it is supposed that the shade picks up the beans and follows behind unseen. Once more he touches water and clashes Temesan* bronze and bids the shade to leave his house. When he has said nine times, ‘Ghosts of my fathers, depart!’ he looks back and considers that he has duly performed the sacred rites. [Ovid, Fasti, 5. 429-444 (early First Century AD)] *Temesa in Bruttium was well known for its copper mines. Ovid begins with a reference to the antiquity of the rite; it is thought that it was a survival from the original inhabitants of the area. The ceremony was performed at midnight when the householder went through the house barefoot. Several reasons are suggested for this. It was a common feature of religious 24 C LAS SI C AL ST UDI E S APP EN D IX ritual that the person performing the ritual should not be constricted in any way; for example, the Flamen Dialis was not permitted to wear an unbroken ring at any time nor, according to Plutarch, to walk under a vine or touch ivy. Leather was taboo in some rituals so footwear may have been banned for this reason. There is also the very old belief that someone performing a religious ritual should remain in direct contact with the earth. He made a magic sign, clenching his fist and pushing his thumb between the first and second finger. This sign was commonly used to avert the evil eye; this appears to be the only description of this in literature but it is often depicted on charms. He then took nine beans in his mouth. He spat these out, dropping them behind him and said, ‘With these words, I ransom me and mine.’ The spirits were then supposed to follow him, picking up and eating the beans. The householder had to keep his head averted, a precaution taken regularly by someone performing a religious ceremony which brought him into contact with superior and potentially dangerous powers. Finally, washing his hands, he clashes bronze objects to make a metallic sound the spirits would dislike and tells them to go with the words, ‘Ghosts of my fathers, depart!’ Bronze was traditionally used in religious ceremonies; a bronze knife was used to cut the hair of the Flamen Dialis, magic herbs were gathered with a bronze sickle and the brooches which fastened the garments of the flamines when sacrificing had to be of bronze. C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY Essential reading Homer, Odyssey Book 11 Virgil, Aeneid Book 6 Higher Classical Studies - Religion and Belief - Starter Materials (Scottish CCC, 1993). See especially Unit 3 (Mystery Religions) and Unit 4 (The Afterlife). Invaluable as a guide to further study and for demonstrating source-based questioning techniques. Contains useful additional bibliographies. Sources to consult Shelton, J. A. - As the Romans Did, Oxford. See Chapter XV - convenient reference point for several sources referred to in text: Bacchanalia (pages 396-401) - Livy Cybele (pages 401-403) - Livy Isis (pages 403-408) - Apuleius Christians (pages 414-417) - Pliny Epicureanism (pages 426-431) - Lucretius Stoicism (pages 431-437) - Seneca Plato Euripides Virgil Ovid Republic 10 614 B Story of Er Phaedrus, Phaedo Bacchae Georgics 4.453ff Orpheus Metamorphoses 15.60ff Pythagoras Books referred to for text Oxford Classical Dictionary - all relevant entries including After Life; Dead, Disposal of Burkert, W., Greek Religion, Blackwell Ferguson, J., The Religions of the Roman Empire, Thames & Hudson Ogilvie, R., The Romans and their Gods, Chatto & Windus Zaidman L. and Pantel, P., Religion in the Ancient Greek City, Cambridge C LAS SI C AL ST UDIE S 26