Abigail Allen Harvard Business School

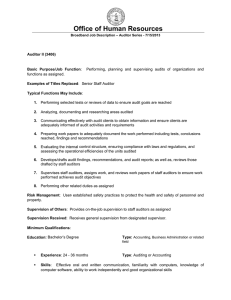

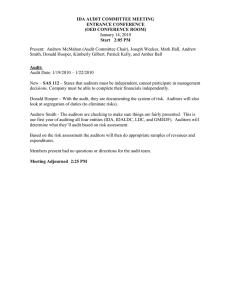

advertisement