PROFITABILITY ASSESSMENT: A CASE STUDY OF AFRICAN (CLARIAS GARIEPINUS) VICTORIA BASIN, KENYA

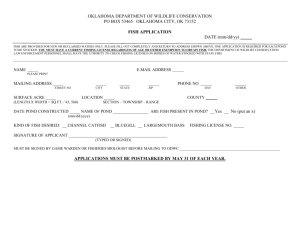

advertisement