Course: Dance Level: Higher March 2014

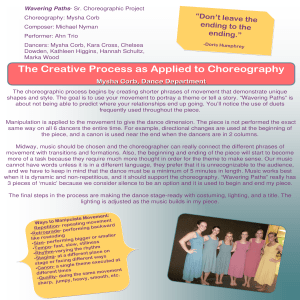

advertisement