Empirical Evidence and Tax Policy Design: Lessons from the Mirrlees Review

advertisement

Empirical Evidence and Tax

Policy Design: Lessons from the

Mirrlees Review

JEEA - Foundation BBVA Lecture

AEA Meetings, Atlanta

January 3rd 2010

Richard Blundell

University College London and Institute for Fiscal Studies

(longer version of lecture on AEA conference website)

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Empirical Evidence and Tax Policy Design

•

First, a little background to the Mirrlees Review

•

Then a discussion on the role of evidence loosely

organised under five headings:

1. Key margins of adjustment to tax reform

2. Measurement of effective tax rates

3. The importance

p

of information,, complexity

p

y and salience

4. Evidence on the size of responses

5. Implications for tax design

•

Focus on earnings,

g , savings

g and indirect tax reform as

leading examples

The Mirrlees Review

Reforming the Tax System for the

21st Century

Editorial Team

Chairman: Sir James Mirrlees

y ((LSE, Bank of England

g

& IFS))

Tim Besley

Richard Blundell (IFS & UCL)

Malcolm Gammie QC (One Essex Court & IFS)

James Poterba (MIT & NBER)

with:

Stuart Adam (IFS)

Steve Bond (Oxford & IFS)

Robert Chote (IFS)

Paul Johnson (IFS & Frontier)

Gareth Myles (Exeter & IFS)

The Mirrlees Review

• Review of tax design from first principles

– For

F modern

d

open economies

i iin generall

– For the UK in particular

• Two volumes:

- ‘Dimensions

Dimensions of Tax Design’:

Design : a set of 13 chapters on

particular areas co-authored by IFS researchers +

international experts, along with expert

commentaries (MRI)

- ‘Tax

Tax by Design’:

Design : an integrated picture of tax design

and reform, written by the editors (MRII)

– http://www.ifs.org.uk/mirrleesReview/publications

htt //

if

k/ i l

R i / bli ti

• MRI on the web and now at the OUP stand…

Dimensions of Tax Design: commissioned chapters

and expert commentaries (1)

•

•

•

The base for direct taxation

James Banks and Peter Diamond; Commentators: Robert Hall; John

K

Kay;

Pierre

Pi

P

Pestieau

ti

Means testing and tax rates on earnings

Mike Brewer

Brewer, Emmanuel Saez and Andrew Shephard; Commentators:

Hilary Hoynes; Guy Laroque; Robert Moffitt

Value added tax and excises

IIan Crawford,

C

f d Michael

Mi h l K

Keen and

d St

Stephen

h S

Smith;

ith C

Commentators:

t t

Richard Bird; Ian Dickson/David White; Jon Gruber

•

Environmental taxation

Don Fullerton, Andrew Leicester and Stephen Smith; Commentators:

Lawrence Goulder; Agnar Sandmo

•

Taxation of wealth and wealth transfers

Robin Boadway, Emma Chamberlain and Carl Emmerson;

y Martin Weale

Commentators: Helmuth Cremer; Thomas Piketty;

Dimensions of Tax Design: commissioned chapters

and expert commentaries (2)

•

•

International capital taxation

Rachel Griffith,, James Hines and Peter Birch Sørensen;; Commentators:

Julian Alworth; Roger Gordon and Jerry Hausman

Taxing corporate income

Alan Auerbach

Auerbach, Mike Devereux and Helen Simpson; Commentators:

Harry Huizinga; Jack Mintz

•

Taxation of small businesses

Claire Crawford and Judith Freedman

•

The effect of taxes on consumption and saving

Orazio Attanasio and Matthew Wakefield

•

Administration and compliance, Jonathan Shaw, Joel Slemrod and John

Whiting; Commentators: John Hasseldine; Anne Redston; Richard

Highfield

•

Political economy of tax reform, James Alt, Ian Preston and Luke

Sibieta; Commentator: Guido Tabellini

Why another Review?

Changes in the world (since the Meade Report)

Changes in our understanding (..)

I

Increased

d empirical

i i l kknowledge

l d ((..))

Increased empirical knowledge: – some examples

•

labour supply responses for individuals and families

– at the intensive and extensive margins

– by age and demographic structure

•

taxable income elasticities

– top of the income distribution using tax return information

•

consumer responses to indirect taxation

– importance of nonseparability and variation in price elasticities

•

i t t

intertemporal

l responses

– consumption, savings and pensions

•

Income uncertainty

– persistence and magnitude of earnings shocks over the life-cycle

•

ability to (micro-)simulate marginal and average rates

– simulate ‘optimal’ reforms

Empirical Evidence and Tax Policy Design

1. Key margins of adjustment to tax reform

2 Measurement of effective tax rates

2.

3. The importance of information, complexity and salience

4. Evidence on the size of responses

5 Implications

5.

I li ti

ffor tax

t design

d i

g , indirect and savings

g taxation:

Here I will focus on earnings,

•

Leading examples of the mix of theory and evidence

•

Key implications for tax design

•

Earnings taxation

taxation, in particular

particular, takes most of the strain in

distributional adjustments of other parts of the reform package

Key Margins of Adjustment

• Intensive and extensive margins of

labour supply

• Taxable income and forms of remuneration

• Consumer demand mix

• Savings

Savings-pension

pension portfolio mix

• Housing equity

• Human capital

• Organisational form

• Debt-equity mix for companies

• Company/R&D location

Key Margins of Adjustment

•

Extensive and intensive margins of labour

supply

•

What do they look like?

–

G tti

Getting

it right

i ht for

f

men

Male Employment by age – US, FR and UK

2007

100%

90%

80%

FR

UK

US

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 72 74

Bozio, Blundell and Laroque

Male Employment by age UK: 1975 - 2005

1

1975

1985

1995

2005

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

05

0.5

0.4

03

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 72 74

Data: UK LFS.

Bozio, Blundell and Laroque

Male Hours by age – US, FR and UK 2005

2200

2000

1800

1600

FR

UK

US

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 72 74

Bozio, Blundell and Laroque

Key Margins of Adjustment

•

Extensive and extensive margins

•

do they l

What d

look

k l

like?

ke

–

Female employment and hours

Female Employment by age in the UK – 1975

- 2005

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

16

18

20

22

24

26

28

30

32

34

36

38

40

1975

42

44

1985

46

48

1995

50

52

54

56

58

60

62

64

66

68

70

72

74

2005

Source: LFS.

Bozio, Blundell and Laroque

Female Hours by age – US, FR and UK 2005

1400

FR

UK

US

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 72 74

Bozio, Blundell and Laroque

Why is this important for tax design?

Implications for the design of tax rates on earnings

1. Suggests where should we look for responses to tax reform.

2 Some key lessons from recent tax design theory (Saez

2.

(Saez,.. )

• Importance of extensive labour supply margin (Heckman,

Rogerson Wise

Rogerson,

Wise, ..))

• A ‘large’ extensive elasticity can ‘turn around’ the impact of

g social weights

g

declining

–

implying a higher transfer to low wage workers than those out of work

–

a role for tax credits

3. But how do individuals perceive the tax rates on earnings

implicit in the tax credit and benefit system - salience?

-

are individuals more likely to ‘take-up’ if generosity increases?

-

how does labour supply in couples respond?

4 Importance of margins other than labour supply

4.

–

taxable income elasticities (at the top)

Top incomes and taxable income elasticities

A . T o p 1 % In c o m e S h a re a n d M T R , 1 9 6 2 -2 0 0 3

80%

16%

70%

14%

12%

T o p 1% M T R

50%

T o p 1 % in c o m e s h a re

40%

10%

30%

8%

Income S

Share

Marginal Ta

ax Rate

60%

20%

6%

10%

2002

2

1998

1

1994

1

1990

1

1986

1

1982

1

1978

1

1974

1

1970

1

1966

1

4%

1962

1

0%

Source: MR, UK SPI (tax return data)

(Some other) Key Margins of Adjustment

•

Consumer demand responses

–

•

Savings-pension portfolio mix

–

•

CGT reforms and the non-alignment with labour income rates

Organisational form

–

•

‘Life-cycle’ accumulation of savings and pension contributions

Forms of remuneration

–

•

responses to differential taxation of across commodities

UK chart on incorporations and tax reforms

Look in the Review documents….

Consumer demand behaviour

•

Three key empirical observations:

•

N

Non-separabilities

biliti with

ith llabour

b

supply

l are iimportant

t t

•

–

but mainly for childcare and work related expenditures

–

updated evidence in MRI

Price elasticities differ with total expenditure/wealth

•

–

responses and welfare impact differs across the distribution

–

new evidence published in Ecta last year

Issues around salience of indirect taxes

–

Chetty et al (AER)

Savings and Pensions

•

When the life-cycle model works

–

How much life-cycle

y

consumption/needs

p

smoothing

g

goes on?

700

3.5

600

3

500

25

2.5

400

2

300

1.5

200

Net Income Per

H

Household

h ld (LH A

Axis)

i )

1

100

Equivalent AdultsPer

Household (RH Axis)

0.5

0

Equiva

alent Adults

s Per Househ

hold

Weekly Income (P

Per Household)

Net Income, Number of Equivalent Adults per

Household

0

20 23 26 29 32 35 38 41 44 47 50 53 56 59 62 65 68 71 74 77

Age of Head

Source: UK FES 1974-2006

Consumption and Needs

3.5

600

Equivilised Non-Durable

Expenditure (LH Axis)

3

500

Equivalent AdultsPer

Household (RH Axis)

2.5

400

2

300

1.5

200

1

100

0.5

0

Numbe

er of Equiv

valent Adullts Per

Hous

sehold

Equiv

vilised Non--Durable Ex

xpenditure

e

(Per Equivalent Adu

ult)

700

0

20 23 26 29 32 35 38 41 44 47 50 53 56 59 62 65 68 71 74 77

A off H

Age

Head

d

Source: UK FES 1974-2006

Savings and Pensions

•

How much life-cycle

life cycle consumption/needs smoothing goes on?

–

permanent/ transitory shocks to income across wealth

distribution ((Blundell,, Pistaferri and Preston ((AER))

))

–

consumption and savings at/after retirement (BBT (AER))

–

how well do individuals account for future changes?

–

•

UK pension reform announcements Attanasio & Rohwedder (AER)

•

Liebman Luttmer & Seif (AER)

Liebman,

Intergeneration transfers - Altonji, Hayashi & Kotlikoff, etc

T

Temporal

l preferences,

f

ability,

bilit cognition,

iti

fframing..

i

–

•

•

Banks & Diamond (MRI chapter); Diamond & Spinnewijn, Saez,..

Earnings/skill uncertainty – across life-cycle and business

cycle

–

Role in dynamic fiscal policy arguments for capital taxation

Kocherlakota; Golosov, Tsyvinski & Werning, ..

Implications for Reform

• Tax Rates on Earnings

• Indirect Taxation

• Corporate Taxation

• Taxation of Savings

• An integrated and revenue neutral

analysis

l i of

f reform…

f

Tax rates on lower incomes

Main defects in current welfare/benefit systems

• Participation tax rates at the bottom remain very high in UK

and elsewhere

• Marginal tax rates in the UK are well over 80% for low

income working families because of phasing-out of meanstested benefits and tax credits

– Working Families Tax Credit + Housing Benefit + etc

– and interactions with the income tax system

– For example, we can examine a typical budget

constraint for a single mother…

The interaction of WFTC with other benefits in the UK

£300 00

£300.00

£250.00

£200.00

WFTC

Income Support

Net earnings

Other income

£150.00

£100.00

£50.00

hours of work

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

£0.00

The interaction of WFTC with other benefits in the UK

£300 00

£300.00

£250.00

Local tax rebate

Rent rebate

WFTC

Income Support

Net earnings

Other income

£200.00

£150.00

£100.00

£50.00

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

£0.00

hours of work

Strongg

implications

for EMTRs,

PTRs and

labour supply

What about the size of labour supply responses?

Structural Model Elasticities – lower educated lone parents

((a)) Youngest

g

Child Aged

g 11-18

Earnings

0

Density

0 3966

0.3966

Extensive

Intensive

80

140

220

300

0.1240

0.1453

0.1723

0 1618

0.1618

0.5029

0.7709

0.7137

0 4920

0.4920

0.5029

0.3944

0.2344

0 0829

0.0829

Participation elasticity

1.1295

Note: Similar strong extensive margin responses for men in

p

period using

p

g structural retirement models and

‘pre-retirement’

for married women with children.

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Importance of take-up and information/hassle costs

0

Proba

ability of ttake-up

.2

.4

..6

.8

1

Variation in take-up probability with entitlement to FC/WFTC

0

50

100

150

FC/WFTC entitlement (£/week, 2002 prices)

Lone parents

200

Couples

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

What about the size of labour supply responses?

Structural Model Elasticities – lower educated lone parents

(c) Youngest Child Aged 0-4

Earnings

Density

Extensive

Intensive

0

0.5942

80

0.1694

0.2615

0.2615

140

0 0984

0.0984

0 6534

0.6534

0 1570

0.1570

220

0.0767

0.5865

0.1078

300

0 0613

0.0613

0 4984

0.4984

0 0834

0.0834

Participation elasticity

0.6352

Differences in intensive and extensive margins by age and

demographics

g p

have strong

g implications

p

for the design

g of the tax

schedule... But how reliable are the structural elasticities?

WFTC Reform Evaluation: Matched Difference-inDifferences

Average Impact on % Employment Rate of Single Mothers

Single Mothers Marginal

Effect

Family

3.5

Resources

Survey

Labour Force

3.6

Survey

Standard

Error

1.55

Sample Size

0.55

233,208

25,163

Data: FRS, 45,000 adults per year, Spring 1996 – Spring 2002.

Base employment level: 45% in Spring 1997.

Outcome: employment. Average impact x 100, employment percentage.

Matching Covariates: age, education, region, ethnicity,..

Drop: Summer 1999 – Spring 2000 inclusive

Expenditure on in-work programmes in the UK

E x p e n d itu re (£ m , 2 0 0 2 p ric e s )

7,000

6,000

5,000

,

WFTC

FC

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

0

1991- 1992- 1993- 1994- 1995- 1996- 1997- 1998- 1999- 2000- 2001- 200292

93 94

95

96

97 98

99 2000 01 02

03

The UK Working Families Tax Credit

• Hours condition

– at

t least

l

t 16 or more hours

h

per week

k

• family eligibility

– children (in full time education or younger)

• income eligibility

– if a family's net income is below a certain

threshold

– adult credit plus age-dependent amounts for

each child

– if above a threshold then credit is tapered

away at 55% per extra pound of net income –

previously 70%

The UK Working Families Tax Credit

£6,000

WFTC

£5,000

£4,000

£3,000

£2,000

£1,000

£0

£0

£5,000

£10,000

£15,000

Gross income (£/year)

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

£20,000

£25,000

The US EITC and the UK WFTC compared

£6,000

£5,000

WFTC

£4,000

,

EITC

£3,000

£2,000

£1,000

£0

£0

£5,000

£10,000

£15,000

£20,000

£25,000

Gross income (£/year)

• P

Puzzle:

l WFTC about

b t ttwice

i as generous as th

the US EITC bbutt

with about half the impact. Why?

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Structural Simulation of the WFTC Reform:

WFTC Tax Credit Reform

All

Change in employment rate:

Average change in hours:

5.95

0 74

0.74

1.79

02

0.2

y-child

0 to 2

3.09

0 59

0.59

0.71

0 14

0.14

y-child

3 to 4

7.56

0 91

0.91

2.09

0 23

0.23

y-child

5 to 10

7.54

0 85

0.85

2.35

0 34

0.34

y-child

11 to 18

4.96

0 68

0.68

1.65

02

0.2

– ‘large’ impact relative to quasi

quasi-experiment

experiment results

Notes: Simulated on FRS data; Standard errors in italics.

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Structural Simulation of the WFTC Reform:

Impact of all Reforms

All

Change in employment rate:

Average change in hours:

•

•

•

•

3.68

0.84

1.02

0 23

0.23

y-child

0 to 2

0.65

0.6

0.01

0 21

0.21

y-child

3 to 4

4.53

0.99

1.15

0 28

0.28

y-child y-child

5 to 10 11 to 18

4.83

4.03

0.94

0.71

1.41

1.24

0 28

0.28

0 22

0.22

matches with the quasi-experimental results

shows the importance of getting the effective tax rates right

predictions are q

quite accurate

shows the structural model p

also use longer changes in after tax wages across different

groups to identify structural responses (BDM, Ecta 1998)

Hours’ distribution for lone parents, 1990

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Hours’ distribution for lone parents, 1993

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Can the reforms explain weekly hours worked?

Single Women (aged 18-45) - 2002

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

An optimal design framework

Social welfare, for individuals of type X

W =∑

∫ε

w, X

*

*

*

Γ

(

U

(

wh

−

T

(

w

,

h

;

X

),

h

; X , ε ))dF (ε )dG(w; X )

∫

where Γ is the ‘social

social welfare

welfare’ transformation.

transformation

The tax structure T(.) is chosen to maximise W, subject

to:

∑∫

*

*

T

(

wh

,

h

; X )dF (ε )dG ( w; X ) = T (= − R )

∫

w, X ε

for a ggiven R.

Control preference for equality by transformation function:

Γ (U | θ ) =

1

(exp U )

{

θ

θ

− 1}

When θ is negative, the function favors the equality of

utilities.

Define u(j) = u(cj , hj ;X,ε). If θ < 0 then the integral

over (Type I extreme

extreme-value)

value) state specific errors is

given by:

1

⎡⎣ Γ (1 − θ ) ⋅ (exp u ( j ))θ − 1⎤⎦

θ

Implied Optimal Schedule, Youngest Child

Aged 0-4

350.00

300.00

250.00

200.00

150.00

100.00

0

50

100

150

No hours rule

200

16 hours rule

250

300

Weekly earnings

March 2002 prices

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Implied Optimal Schedule, Youngest Child

Aged 5-10

350.00

300.00

250.00

200.00

150 00

150.00

100.00

0

50

100

150

No hours rule

200

16 hours rule

250

300

Weekly earnings

March 2002 prices

Blundell and Shephard (2008)

Implications for Tax Rates

• Change transfer/tax rate structure to match lessons from

‘new’ optimal tax analysis and empirical evidence:

• Lower marginal rates at the bottom

• means

means-testing

testing should be less aggressive

• at least for some groups =>

• Age-based taxation

– distinguish

g

by

y age

g of yyoungest

g

child for

mothers/parents

– pre

pre-retirement

retirement ages

• Hours rules? – at full time, welfare gains depend on monitoring

• Impact of reforms on PTRs and EMTRs (MRII)) →

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Effect of child age revenue neutral reforms on average PTRs across the

earnings distribution, by age of youngest child

0

100

200

Notes: Non-par

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000 1100 1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Y

Youngest

t child

hild 0

0-4,

4 before

b f

reform

f

Y

Youngest

t child

hild 0

0-4,

4 after

ft reform

f

Youngest child 5-18, before reform

Youngest child 5-18, after reform

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Effect of early retirement revenue neutral reforms on average PTRs across

the earnings distribution, by age

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000 1100 1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Under 55

55, before reform

55-70, before reform

Under 55

55, after reform

55-70, after reform

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Effect of early retirement revenue neutral reforms on average EMTRs across

the earnings distribution, by age

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900 1000 1100 1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Under 55,

55 before reform

55-70, before reform

Under 55

55, after reform

55-70, after reform

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Effect of child age revenue neutral reforms on average EMTRs across the

earnings distribution, by age of youngest child

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000 1100

1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Youngest child 0-4, before reform

Youngest child 0-4, after reform

Youngest child 5-18, before reform

Youngest child 5-18, after reform

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Implications for Tax Rates

• These child-age tax reforms redistribute to families with

younger children and increase employment by 40,000,

aggregate

t earnings

i

up by

b £

£.7m

7

• Important employment increases also from pre-retirement

age tax reforms

– retirement incentives highlight the interaction between the taxation of

earnings and the taxation of savings and pensions =>

• Effective tax rates on earnings are a combination of the tax

rate on earnings and on savings/pensions

– how do individual’s p

perceive p

pension contributions?

– assumptions about intertemporal behaviour are so critical

– Leibman, Luttmer and Seif suggest extensive margin... return to this

• What about the design of tax rates on high earnings?

Taxable income elasticities

An ‘optimal’ top tax rate (Brewer, Saez and Shephard, MRI)

e – taxable income elasticity

t = 1 / (1 + a·e) where a is the Pareto parameter.

Estimate e from the evolution of top incomes in tax return

data following large top MTR reductions in the 1980s

( 1.8)) from the empirical

p

distribution

Estimate a(≈

Table: Taxable Income Elasticities at the Top

Simple Difference (top 1%)

1978 vs 1981

1986 vs 1989

1978 vs 1962

2003 vs 1978

F ll titime series

Full

i

DD using top 5-1% as control

0.32

0.38

0.63

0.89

0.08

0.41

0.86

0.64

0.69

0

69

(0.12)

0.46

0

46

(0.13)

With updated data the estimate remains in the .35 - .55 range

with a central estimate of .46,, but remain quite

q

fragile

g

Note also the key relationship between the size of elasticity and

the tax base (Slemrod

(S

and Kopczuk, 2002))

Pareto distribution as an approximation to the income distribution

Pro

obability density ( log scale )

0.0100

Pareto distribution

Actual income distribution

0.0010

0.0001

0.0000

0.0000

£100 000 £150,000

£100,000

£150 000 £200,000

£200 000 £250,000

£250 000 £300,000

£300 000 £350,000

£350 000 £400,000

£400 000 £450,000

£450 000 £500,000

£500 000

Change in tax revenue as a result of changing marginal

income tax rate applying to the top 2%

%

Chang

ge in tax re

evenue, £ m

million

£4 000

£4,000

£3,000

£2 000

£2,000

e=0.46

e=0.35

e=0

£1,000

£0

-£1,000

-£2,000

,

-£3,000

-£4,000

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

Income tax rate

55%

60%

65%

Reforming Tax Rates

• Change transfer/tax rate structure to match lessons from ‘new’

optimal tax analysis

– limits

li it tto ttax rises

i

att th

the ttop, but

b t

• anti-avoidance, domicile rules, .. - tax base reforms

• revenue shifting

hifti

– lower marginal rates at the bottom

• means-testing

i should

h ld b

be lless aggressive

i

• Age-based taxation

– distinguish by age of youngest child

– pre-retirement ages

• Integrate different benefits and tax credits

– improve administration, transparency, take-up, facilitate coherent

design

• Undo distributional effects of the rest of the package…

Indirect Taxation

• Evidence on consumer behaviour => exceptions to uniformity

– Childcare strongly complementary to paid work

– Various work related expenditures (QUAIDS on FES, MRI)

– Human capital

p

expenditures

p

– ‘Vices’: alcohol, tobacco, betting, possibly unhealthy food have

externality / merit good properties Î keep ‘sin taxes’

– Environmental externalities (three separate chapters in MRII)

• These do not line up

p well with existing

g structure of taxes

⇒Broadening the base – many zero rates in UK VAT

• Compensating losers,

losers even on average,

average is difficult

• Worry about work incentives too

• W

Workk with

ith sett off direct

di t tax

t and

d benefit

b

fit instruments

i t

t as in

i earnings

i

tax reforms

Indirect Taxation – UK case

Zero rated:

Zero-rated:

Food

Construction of new dwellings

Domestic passenger transport

I t

International

ti

l passenger transport

t

t

Books, newspapers and magazines

Children’s clothing

ugs a

and

d medicines

ed c es o

on p

prescription

esc pt o

Drugs

Vehicles and other supplies to people with disabilities

Cycle helmets

Reduced-rated:

D

Domestic

ti fuel

f l and

d power

Contraceptives

Children’s car seats

g cessation p

products

Smoking

Residential conversions and renovations

VAT-exempt:

Rent on domestic dwellings

R t on commercial

Rent

i l properties

ti

Private education

Health services

Postal services

Burial and cremation

Finance and insurance

Estimated cost (£m)

11,300

8,200

2,500

150

1,700

1,350

,350

1,350

350

10

2,950

2

950

10

5

10

150

3,500

200

300

900

200

100

4,500

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Impact on budget share of an additional hour worked

Conditional on income and prices

Bread and Cereals

Negative

Meat and Fish

Negative

g

Dairy products

Negative

Tea and coffee

Negative

Fruit and vegetables

Negative

Food eaten out

Positive

Beer

Positive

Wine and spirits

Positive

Domestic fuels

Negative

Household goods and services

Positive

g

Adult clothing

Positive

Childrens’ clothing

Negative

Petrol and diesel

Positive

Leisure goods and services

Positive

Source: QUAIDS on UK FES, MRI

Compensation package involves:

• A 3.1% increase in all benefits and tax

thresholds.

• A 6.2% increase for the main means-tested

benefits, and for the working tax credit for

non parents.

non-parents.

• An additional 16.9% rise (so giving 20% in

total) in child benefit. This rises from £20 to

£24 a week for the first child, and from £13.20

to £15.80 a week for additional children.

• A further £600 increase in the income tax

allowance for the under 65s, and an increase of

£1,200 for the over 65s. This change has the

effect of taking 1¼ million people out of

income tax.

• A £3,200 cut in the limit for basic rate tax

and the upper earnings

i

limit

i i for National

i

Insurance. This leaves these limits £1,000

below the current nominal level.

Effect of base broadening reform with earnings

t reform

tax

f

compensation,

ti

by

b expenditure

dit

decile

d il

% rise in COL

% rise in inc

cash gain/loss

9%

£10

8%

£8

7%

£6

6%

£4

5%

£2

4%

£0

3%

-£2

2%

-£4

1%

-£6

0%

-£8

Poorest

2

3

4

5

6

7

Expenditure decile group

8

9

Richest

Effect of base broadening reform with earnings tax

instruments as compensation (MRII), by income decile

Reform revenue neutral and designed to leave effective

tax rates on earnings unchanged

40%

45%

50%

55%

5

60%

6

EMTR: before and after indirect tax reform

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000 1100 1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Before reform

After reform

Reform revenue neutral and designed to leave effective

tax rates on earnings unchanged

35%

40%

45%

4

50%

5

55

5%

PTR: before and after indirect tax reform

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000 1100 1200

Gross earnings (£/week)

Before reform

After reform

Broadening the base of indirect taxation

• Empirical results suggest current indirect tax rates do not

line up with any reasonable justification and are a poor

way of delivering redistribution given the other tax

instruments available

– Interpretation of results is that we can implement a reform

package

p

g manages

g to achieve compensation

p

while also

avoiding significant damage to work incentives.

– On average the EMTR rise by less than a quarter of a

percentage point and the PTR by less than half a

percentage point.

– little change in work incentives at any earnings level

• Quite sizable welfare gains from removing distortions =>

Welfare gains - Distribution of EV/x by ln(x)

ln x

Source: MRII

The shape of a reform package

• Broaden VAT base

– keep

p childcare differentiation,, sin taxes + reformed

environmental taxes/permits, etc

• Reforms to the income tax / benefit rate schedule

– Apply lessons from empirical evidence on response elasticities

– Compensate

C

t for

f distributional

di t ib ti

l effects

ff t off reform

f

package

k

• Interaction with taxation of corporate profits and the taxation of

saving

Interaction with Corporate Taxation

•

Exempt normal rate to give neutrality between debt and equity

– move toward a source-based

source based ACE system

– recognising that taxing corporate rents on a destination-basis may

be more

o e att

attractive

act e in tthe

e longer

o ge te

term,, pa

particularly

t cu a y if ssignificant

g ca t

revenues from source-based corporate taxes eventually prove to be

unsustainable

•

A progressive rate structure for the shareholder income tax,

((rather than the flat rate proposed

p p

by

y GHS in MRI))

– with progressive tax rates on labour income, progressive rates are

q

on shareholder income to avoid differential tax

also required

treatments of incorporated and unincorporated firms

–

a lower progressive rate structure on shareholder income than on

labour income reflects the corporate tax already paid

Interaction with Corporate Taxation

•

Suitable rate alignment between tax rates on corporate

income, shareholder income and labour income

–

•

deals with many issues in the MRI evidence on small business

taxation

Note current rates on labour income (top 45%) and capital

gains (18%)!

Interaction with the Taxation of

Saving

•

•

Organising principal around which we begun was the

‘expenditure tax’ as in Meade/Bradford but with adaptations

–

coherent approach to taxation of earnings and savings over the

life-cycle – lifetime base

–

provides a framework for the integration of capital income

taxation with corporate taxation

–

capital gains and dividends treated in the same way and

overcomes ‘lock-in’ incentive from CGT

–

can incorporate

p

p

progressivity

g

y and captures

p

excess returns

taxing saving is an inefficient way to redistribute

- assuming that the decision to delay consumption tells us nothing

about ability to earn

•

implies zero taxation of the normal return to capital

–

can be achieved through alternative forms: EET, TEE, TtE(RRA)

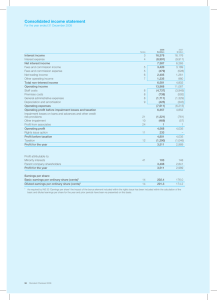

Fraction of wealth held in different tax treatments in UK

Decile of

gross

financial

wealth

Range of

gross

financial

wealth

(£’000s)

Proportion of wealth held

in:

Private

ISAs

Other

pensions

assets

Poorest

0 126

0.126

0 091

0.091

0 783

0.783

2

<1.7

<1

7

1.7–16.6

0.548

0.138

0.315

3

16.6–39.1

0.652

0.110

0.238

4

39.1–75.9

0.682

0.108

0.210

5

75.9–122.3

0.697

0.079

0.223

6

122.3–177.2

0.747

0.068

0.185

7

177.2–245.4

0.781

0.062

0.157

8

245 4 350 3

245.4–350.3

0 818

0.818

0 046

0.046

0 136

0.136

9

350.3–511.2

0.790

0.057

0.153

Richest

>511.2

0.684

0.044

0.273

0.736

0.055

Source:All

ELSA, 2004 – at least one member

aged 52-64

0.209

Unfortunately…

Conditions for zero rate on normal return can fail if:

1. Heterogeneity (e.g. high ability people have higher saving rates)

– new evidence and theory, Banks & Diamond (MRI); Laroque, Gordon &

Kopczuk; Diamond & Spinnewijn; …

2 Earnings

2.

E i

risk

i k and

d credit

dit constraints

t i t

– new theory and evidence on earnings ability risk, Golosov, Tsyvinski &

W i

Werning;

Bl

Blundell,

d ll P

Preston

t & Pi

Pistaferri;

t f i C

Conesa, Kit

Kitao & K

Krueger

– e.g. keep wealth low to reduce labour supply response, weaken

incentive compatibility constraint

3. Outside (simple) life-cycle savings models

- myopia; self-control problems; framing effects; information monopolies

4. Non-separability (timing of consumption and labour supply)

5. Evidence suggests a need to adapt standard expenditure tax

arguments

Correct some of the obvious defects:

•

•

•

C

Capture

excess returns and

d rents

–

move to RRA(TtE) or EET where possible – neutrality across assets

–

TEE limited

li it d llargely

l tto iinterest

t

tb

baring

i accounts

t

–

Lifetime accessions tax across generations, if practicable.

P

Pensions

i

- allow

ll

some additional

dditi

l iincentive

ti tto llock-in

k i savings

i

–

twist implicit retirement incentives to later ages

–

current tax free lump sum in UK is too generous and accessed too early

Housing

–

add

dd VAT style

t l property

t tax

t on consumption

ti (rH)

( H)

–

excess returns? Currently TEE in UK – difficult without LVT issues

•

Broaden VAT base

•

Reforms to the income tax / benefit rate schedule

–

Apply lessons from empirical evidence on response elasticities

–

Compensate for other reforms

Empirical Evidence and Tax Policy Design:

L

Lessons

ffrom th

the Mi

Mirrlees

l

R

Review

i

Five building blocks for the role of evidence in tax design

design….

•

Key margins of adjustment to tax reform

•

Measurement of effective tax rates

•

Th importance

The

i

t

off information,

i f

ti

complexity

l it and

d salience

li

•

Evidence on the size of responses

•

Implications for tax design

see

http://www.ifs.org.uk/mirrleesReview

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

But (too) many key issues unresolved, and with little

evidence base (!)

Including:

• Tax credits and earnings progression

• Distinction between dynamic and static policies

• Human capital investment bias and savings taxation

• Taxation of financial services

• Some transition issues and capitalisation

p

• ….

10

00

M

Monthly

earnings

e

200

300

400

SSP: Monthly earnings by months after RA

0

10

20

30

40

Months after random assignment

control

t l

50

60

experimental

i

t l

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

6

Hourly rea

H

al wages

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

and dynamic effects on wages and productivity?

0

10

20

30

40

Months after random assignment

control

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

experimental

50

60

Dynamic Effects from the Canadian SSP

• Earnings and employment line up with

control group after time limit is

exhausted

• Littl

Little evidence

id

of

f employment

l

t

enhancement or wage progression

• Other evidence, Taber etc, show some

progression but quite small

• Key area of research

• Some more optimistic results for some

recent UK policies

• What

Wh t about

b t age-based

b

d policies?

p li i ?

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Some Additional References:

Banks, JJ., Blundell

Banks

Blundell, R

R., and Tanner

Tanner, S

S. (1998) “Is

Is there a retirement

retirement-savings

savings

puzzle?”, American Economic Review, 88, 769 – 788.

Besley, T. and S. Coate (1992), “Workfare

Workfare versus Welfare: Incentive Arguments

for Work Requirement in Poverty Alleviation Programs”, American Economic

Review, 82(1), 249-261.

Blundell, R. (2006), “Earned income tax credit policies: Impact and Optimality”,

The 2005 Adam Smith Lecture, Labour Economics, 13, 423-443.

Blundell, R

Blundell

R.W.,

W Duncan

Duncan, A

A. and Meghir

Meghir, C

C. (1998)

(1998), "Estimating Labour Supply

Responses using Tax Policy Reforms", Econometrica, 66, 827-861.

Blundell, R

Blundell

R, Duncan

Duncan, A

A, McCrae

McCrae, J and Meghir

Meghir, C

C. (2000)

(2000), "The

The Labour Market

Impact of the Working Families' Tax Credit", Fiscal Studies, 21(1).

Blundell, R. and Hoynes, H. (2004), "In-Work Benefit Reform and the Labour

Market", in Richard Blundell, David Card and Richard .B. Freeman (eds)

Seeking a Premier League Economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blundell,

Bl

d ll R

R. and

dM

MaCurdy

C d (1999)

(1999), "Labour

"L b

Supply:

S

l A Review

R i

off Alternative

Alt

ti

Approaches", in Ashenfelter and Card (eds), Handbook of Labour Economics,

Elsevier North-Holland.

Blundell, R., Meghir, C., and Smith, S. (2002), ‘Pension incentives and the

pattern of early

p

y retirement’, Economic Journal, 112, C153–70.

Blundell, R., and A. Shephard (2008), ‘Employment, hours of work and the

optimal taxation of low income families’, IFS Working Papers , W08/01

Brewer, M. A. Duncan, A. Shephard, M-J Suárez, (2006), “Did the Working

Families Tax Credit Work?”, Labour Economics, 13(6), 699-720.

Card, David and Philip K. Robins (1998), "Do Financial Incentives Encourage

Welfare Recipients To Work?", Research in Labor Economics, 17, pp 1-56.

Chetty, R

Chetty

R. (2008)

(2008), ‘Sufficient

Sufficient statistics for welfare analysis: a bridge between

structural and reduced-form methods’, National Bureau of Economic Research

(NBER), Working Paper 14399

Diamond, P. (1980): "Income Taxation with Fixed Hours of Work," Journal of

Public Economics, 13, 101-110.

Eissa, Nada and Jeffrey Liebman (1996), "Labor Supply Response to the

Earned Income Tax Credit", Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXI, 605-637.

IImmervoll,

ll H

H. Kl

Kleven, H

H. K

Kreiner,

i

C

C, and

dS

Saez, E

E. (2005)

(2005), `W

Welfare

lf

Reform

R f

in

i

European Countries: A Micro-Simulation Analysis’ Economic Journal.

Keane, M.P. and Moffitt, R. (1998), "A Structural Model of Multiple Welfare

Program

g

Participation

p

and Labor Supply",

pp y International Economic Review,

39(3), 553-589.

Kopczuk, W. (2005), ‘Tax bases, tax rates and the elasticity of reported income’,

J

Journal

l off P

Public

bli E

Economics,

i

89 2093

89,

2093–119.

119

Laroque, G. (2005), “Income Maintenance and Labour Force Participation”,

Econometrica 73(2),

Econometrica,

73(2) 341-376

341-376.

Mirrlees, J.A. (1971), “The Theory of Optimal Income Taxation”, Review of

Economic Studies,, 38,, 175-208.

Moffitt, R. (1983), "An Economic Model of Welfare Stigma", American Economic

Review, 73(5), 1023-1035.

Phelps, E.S. (1994), “Raising the Employment and Pay for the Working Poor”,

American Economic Review, 84 (2), 54-58.

Saez, E. (2002): "Optimal Income Transfer Programs: Intensive versus

Extensive Labor Supply Responses," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117,

1039-1073.

Sørensen , P. B. (2009) “Dual income taxes: a Nordic tax system”, Paper

prepared for the conference on New Zealand Tax Reform – Where to Next?.

ETRs for basic-rate taxpayer (BRT) and higher-rate taxpayer (HRT)

Asset

Effective tax rate (%)

BRT

HRT

ISA (cash

(

h or stocks

t k and

d shares)

h

)

0

0

Cash deposit account

33

67

E l

Employee

contribution

t ib ti tto pension

i

(i

(invested

t d 10 years))

–21

21

–53

53

(invested 25 years)

–8

–21

(invested 10 years)

–115

–102

(invested 25 years)

–45

–40

0

0

((invested 10 years)

y

)

10

35

(invested 25 years)

7

33

Employer contribution to pension

Owner-occupied housing

Stocks and sharesb

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

Effective tax rates on returns to pension saving

Asset

Effective tax rate (%)

Employee contribution to a pension

Tax rate in work

Tax rate in retirement

Basic rate ((20%))

Basic rate ((20%))

–21

Higher rate (40%)

Higher rate (40%)

–53

Higher rate (40%)

Basic rate (20%)

–122

Basic rate (20%)

Pension credit taper (40%)

Tax credit taper (59%)

Basic rate (20%)

–260

T credit

Tax

dit ttaper (59%)

P

Pension

i credit

dit ttaper (40%)

–189

189

© Institute for Fiscal Studies

46

Interaction with Corporate Taxation

•

A progressive rate structure for the shareholder income tax,

rather than the flat rate p

proposed

p

by

y GHS in MRI

– with progressive tax rates on labour income, progressive rates are

also

a

so required

equ ed o

on sshareholder

a e o de income

co e to

oa

avoid

odd

differential

e e a tax

a

treatments of incorporated and unincorporated firms

–

•

Suitable rate alignment

g

between tax rates on corporate

p

income, shareholder income and labour income

–

•

a lower p

progressive

g

rate structure on shareholder income than on

labour income reflects the corporate tax already paid

deals with many issues in the MRI evidence on small business taxation

Note current rates on labour income (top 45%) and capital

gains (18%)!

© Institute for Fiscal Studies