Human Capital, Inequality and Tax Reform: Recent Past and Future Prospects

advertisement

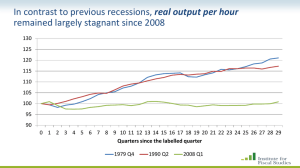

Human Capital, Inequality and Tax Reform: Recent Past and Future Prospects Coase Lecture LSE March 10th 2015 Richard Blundell* University College London and Institute for Fiscal Studies** * Thanks to Monica Costa-Dias, Jonathan Cribb, Ben Etheridge, Andy Hood, Michelle Jin, Rob Joyce, Helen Miller, and Cormac O’Dea for helpful discussions. ** This research is funded by the ERSC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS. Human Capital, Inequality and Tax Reform • Even before the recent crisis, many economies and their governments around the developed world faced growing inequality and pressure to increase employment and earnings. • The depth of the recent recession has added to this and brought further pressure on government revenues. I focus here on the UK and ask three general questions: 1. What has happened to living standards and inequality? 2. Where will tax/welfare reform to have most impact? 3. How has this changed in the light of the great recession? I will conclude with some prospects for the UK economy and for reform… Human Capital, Inequality and Tax Reform • The emphasis will be on the labour market and on personal tax and welfare reforms. • Many of the key determinants of trends in income inequality and in overall living standards over the past 25 years, including since the financial crisis, have been driven by changes in the labour market, including: – huge increase in entry cohorts with at least a BA degree during the 1990s and early 2000s, – large relative rise in top ‘earnings’ percentile since the early 1990s, – dramatic fall in real wages since 2008, …. • To which we can add changes in asset prices, in particular housing; immigration; and, of course, reforms to taxes and welfare benefits. 1. What has happened to living standards and inequality? To dig a little deeper into this, and the other questions, I look at three measures that all have something important to say: A. Earnings: Employment, Wages, Human Capital (and Productivity) B. Incomes: Working-age mainly C. Consumption: Durable and Non-durable Expenditures wages => earnings => joint earnings => income => consumption To investigate the links between them I draw on some recent research: Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK. IFS Report Series What Can Wages Tell Us about the Productivity Puzzle? Economic Journal Household Consumption through Recent Recessions. Fiscal Studies Female Labour Supply, Human Capital and Tax Reform, NBER/IFS WP Family Labour Supply and Consumption Inequality, NBER/IFS WP Prospects preview…. • Younger workers and families are acting as if they expect a long-run fall in relative living standards – the pattern of low real wages at the bottom looks set to continue, but with buoyant employment, – low skilled workers will increasingly rely on the benefit/tax credit system and family labour supply, – longer term earnings growth will mostly come from high-skilled occupations. • With growing earnings inequality there is increasing pressure on the tax and welfare system. – current tax systems raise revenue/redistribute inefficiently and unfairly. – some potential big gains from tax/welfare reforms to enhance human capital and earnings, and address inequality. • Productivity, though, is still the key. A. Earnings: wages, employment (and productivity) • Average real hourly wages fell back strongly after the onset of the recession – even though workforce composition has shifted towards more productive types. • Real wage falls occurred within individuals: – unprecedentedly high proportions of employees experienced effectively nominal wage freezes. • The education premium survived the large increase in those with BAs – but real wages have fallen for all groups since the recession. • ‘Effective’ labour supply, particularly female labour supply, was higher than during previous recessions – due partly welfare policy changes and partly to wealth and long run real wage declines. © Institute for Fiscal Studies Changes to total output, employment and hours worked since 2008Q1 Indexed to 100 in 2008Q1 105 100 95 Output 90 Source: Cribb and Joyce (IFS, 2015) Employment Total hours Changes to productivity since 2008 (2008Q2=100) Indexed to 100 in 2008Q1 105 100 95 Output per worker 90 Source: Cribb and Joyce (IFS, 2015) Output per hour worked In contrast to previous recessions, real output per hour has at best been quite stagnant since 2008 Real output per hour 120 115 110 105 100 95 90 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Quarter since the labelled one 1979Q4 1990Q2 2008Q1 Mean weekly earnings since 2001 adjusted for RPIJ inflation (indexed to 100 in 2008Q1) 105 100 95 90 AWE 85 Source: Cribb and Joyce (IFS, 2015) LFS ASHE Changes to real median hourly wages by age group 110 Real earnings indexed to 100 in 2008 22-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60+ 105 100 95 90 85 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Notes: Results adjusted for methodological changes in 2011. Earnings observed in April of each year. Source: Cribb and Joyce (2015), calculations using Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. 2013 2014 Change in real median hourly wages by age group since 2008 Cumulative change in real median hourly wages from 2008 to 2014 2% 0.2% 0% -2% -2.7% 40-49 50-59 -4% -6% -5.8% -8% -10% -9.0% 22-29 © Institute for Fiscal Studies -2.6% 30-39 Source: Figure 2.11b of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” 60 + Change in real median hourly wages by sex since 2008 Cumulative change in real median hourly wages from 2008 to 2014 2% 0% -2% -2.5% -4% -6% -8% -7.3% -10% Men © Institute for Fiscal Studies Women Source: Figure 2.10 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” % annual change to real hourly wage, by period Falls even greater after allowing for composition changes in mean real hourly earnings 1.5% Average annualised change 1.1% 1.0% 0.7% 0.6% 0.6% 0.5% 0.5% 0.0% -0.5% -0.4% -0.6% -1.0% -1.0% -1.2% -1.5% 2002-2007 Actual change Source: Cribb and Joyce (IFS, 2015) 2007-2012 Compositional effect 2012- 2014 Underlying change Growth in proportion with degrees or above by age: all Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) Ratio of BA (equiv.) median wage to that of A-level (equiv.) Remarkably… no cohort effects! BA premium stayed largely constant, even through the recession. Excluding immigrants Including immigrants Male Female ‘Experience’ wage profiles show strong complementarity between schooling and on the job human capital - UK Women Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2014) Employment and labour market participation • Labour market participation held up better during this past recession than previous ones. For example: – Employment rates fell less (and unemployment rates increased less) Employment rate (age 16-64) (%) Female employment stronger than male employment since the recession 80% 75% 70% 65% Male Female © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Fig 2.1 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” 2014Q3 2014Q1 2013Q3 2013Q1 2012Q3 2012Q1 2011Q3 2011Q1 2010Q3 2010Q1 2009Q3 2009Q1 2008Q3 2008Q1 2007Q3 2007Q1 2006Q3 2006Q1 2005Q3 2005Q1 60% Employment and labour market participation • Some increase of participation can be attributed policy changes, e.g. : – Labour supply has increased among lone parents as a result of job search conditions attached to benefit claims – Older workers are retiring later as a result of increased SPA for women Change to lone mothers’ participation rate since policy change 14% 12% 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% -2% -4% -6% -8% 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Quarter since the last quarter before policy change youngest kid 12-15, 2008Q3 youngest kid10-11, 2009Q3 youngest kid 7-9, 2010Q3 Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) youngest kid 5-6, 2011Q3 15 Impact of SPA increase for women on employment 60% 55% 50% Counterfactual male 60-64 employment rate LFS employment rate 60-64 men 45% Counterfactual female 60-64 employment rate 40% LFS employment rate 60-64 year old women 35% 30% Note: counterfactual employment rates are estimated. See Cribb et al (IFS, 2013) “Incentives, shocks or signals: labour supply effects of increasing the female state pension age in the UK” Focus on employment rates of older women, 2003 to 2014 80% 70% Employment rate 60% 50% 40% Age 58 Age 60 30% 20% 10% 0% © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Fig 1 of Cribb, Emmerson and Tetlow (2014) “Labour supply effects of increasing the female state pension age in the UK from age 60 to 62” IFS Working Paper WP 14/19 Age 61 Age 62 Employment and self-employment rate of older people (wealth and wage effects?) 4% 2% -2% -4% -6% -8% employment rate 60-74 male self-employment rate 60-74 male employment rate 60-74 female self-employment rate 60-74 female 2012Q3 2012Q1 2011Q3 2011Q1 2010Q3 2010Q1 2009Q3 2009Q1 2008Q3 2008Q1 2007Q3 2007Q1 2006Q3 2006Q1 2005Q3 2005Q1 2004Q3 2004Q1 2003Q3 2003Q1 2002Q3 2002Q1 2001Q3 -10% 2001Q1 2007Q4 = 0 0% Employment rate for older workers: women aged 60-64 45.0 40.0 35.0 Euro area (13 countries) 30.0 Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) 25.0 Spain France 20.0 Italy 15.0 United Kingdom 10.0 5.0 0.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Employment rate for older workers: men aged 65-69 30.0 25.0 Euro area (13 countries) 20.0 Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) Spain 15.0 France Italy 10.0 United Kingdom 5.0 0.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 For the young employment fell back.... Employment rate: men aged 25-29 90.0 85.0 Euro area (13 countries) 80.0 Germany (until 1990 former territory of the FRG) Spain 75.0 France Italy 70.0 United Kingdom 65.0 60.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 B. Income Growth and Income Inequality: setting the scene • Leading up the recession: • income growth had slowed in early 2000s. • pensioners/ working-age childless were doing relatively well/badly • During recession and immediately afterwards: • real earnings for those in work fell • employment rates fell for low skilled young adults but not for older ones • benefits/tax credit incomes were working harder • As a result • income inequality fell (despite rise in earnings inequality among workers) • low educated young adults did worst; pensioners did best • Average incomes have now stabilised • but significant falls in previous years leave mean income 8.5% below peak • reflects sharp drop in real earnings, large falls in pre-tax earned income of households between, despite higher employment Income growth slowed from the early 2000s... 125 Mean income Median Income 1997–98=100 120 115 110 105 100 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Figure 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: IFS 2014 Income growth slowed from the early 2000s... 125 Mean income Median Income 1997–98=100 120 115 110 105 100 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Figure 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 ... followed by large falls in 2010–11 and 2011–12... 125 Mean income Median Income 1997–98=100 120 115 110 105 100 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Figure 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 ... before average incomes began to stabilise 125 Mean income Median Income 1997–98=100 120 115 110 105 100 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Figure 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 Income sources, 2007–08 to 2009–10: steady income growth due to benefits/tax credits Earnings 0.1 Benefits and tax credits 2.2 Savings and private pension income -0.7 Self-employment income 0.4 Other 0.2 Taxes and other deductions 0.2 Total income 2.4 -2 -1 0 1 Contribution to income growth between 2007–08 to 2009–10 (in percentage points) Source: Table 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income statistics. Households with negative incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income © Institute for Fiscal Studies 2 3 Income sources, 2009–10 to 2012–13: large income falls due to falling earnings Earnings -8.1 Benefits and tax credits -1.0 Savings and private pension income -0.8 Self-employment income -1.7 Other -0.2 Taxes and other deductions 3.2 Total income -8.6 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 Contribution to income growth between 2009–10 to 2012–13 (in percentage points) Source: Table 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income statistics. Households with negative incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income © Institute for Fiscal Studies 0 2 4 Income sources: 2007–08 to 2012–13 Earnings -8.2 Benefits and tax credits 1.2 Savings and private pension income -1.5 Self-employment income -1.4 Other 0.1 Taxes and other deductions 3.5 Total income -6.4 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 Contribution to income growth between 2007–08 to 2011–13 (in percentage points) Source: Table 2.3 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 Notes: This is a very slightly different sample to the overall income statistics. Households with negative incomes are dropped. This makes a small difference to falls in income © Institute for Fiscal Studies 2 4 6 Cumulative real change Weekly earnings inequality (among workers) rose between 2007-08 to 2012-13... 0.0% -1.0% -2.0% -3.0% -4.0% -5.0% -6.0% -7.0% -8.0% -9.0% -10.0% -11.0% -12.0% -13.0% -14.0% 10 Note: Excludes self-employment income Source: Family Resources Survey, various years 20 30 40 50 60 Percentile point 70 80 90 ...but net result was still a fall in income inequality 8% Income change 4% 0% -4% -8% 2007–08 to 2009–10 2009–10 to 2012–13 2007–08 to 2012–13 -12% 10 20 30 40 50 60 Percentile point Source: Family Resources Survey, various years © Institute for Fiscal Studies 70 80 90 Transfer system doing more work: Real private and net income growth, 2007–08 to 2012–13 4% 2% Cumulative income change 0% -2% -4% -6% -8% -10% -12% -14% Net income Private income -16% -18% 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 Percentile © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 70 75 80 85 90 95 Will it continue? Future benefit and tax changes are important drivers in income distribution, Simulations up to 2015–16: 4% Income change 2% 0% -2% -4% 2007–08 to 2012–13 -6% 2012–13 to 2015–16 -8% 10 20 30 40 50 60 Percentile point 70 80 Note: Figure is an update of that in Brewer et. al. (2013), Fiscal Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 179–201. © Institute for Fiscal Studies 90 Marginal income tax + NICs rate Two aspects of the Tax System: 1. Effective taxes on Higher Incomes. Marginal tax rates by income level 2011 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% Income tax + NICs 20% Income tax 10% 0% 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Employer cost (£000s) Source: Mirrlees Review 160 180 200 Two aspects of the Tax System: 1. Effective taxes on Higher Incomes. Marginal tax rates by income level, UK 45% 40% 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% Earned income Self employment income Dividend income 10% 5% 0% $0 $10,000 $20,000 $30,000 $40,000 $50,000 Gross income Note: assumes dividend from company paying small companies’ rate. Includes income tax, employee and self-employed NICs and corporation tax. © Institute for Fiscal Studies Bunching at the higher rate threshold, UK Number in each £100 bin 300000 250000 200000 150000 100000 50000 0 Distance from threshold © Institute for Fiscal Studies Composition of income around the higher rate tax threshold Total income per £100 bin (£ billion) Interest $9 $8 $7 $6 $5 $4 $3 $2 $1 $0 -$1 Property Dividends Other investment income Self employment Other Pensions Benefits Employment Deductables Distance from threshold © Institute for Fiscal Studies 2. Effective Taxes for families at the Bottom: Complex but redistributive, budget constraint for single parent in 2011 Notes: wage £6.50/hr, 2 children, no other income, £80/wk rent. Ignores council tax and rebates Measures of inequality: 50/10, 90/50 ratios 2.300 2.200 2.100 Ratio 2.000 1.900 1.800 1.700 1.600 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 1.500 50/10 © Institute for Fiscal Studies 90/50 Source: Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 But top 1% share continued to grow dramatically 90/10 ratio and top 1% income share 10% 9% 4 8% 7% 3 6% 5% 2 4% 3% 1 2% 90/10 ratio (LH axis) Top 1% share of income (RH axis) 0 © Institute for Fiscal Studies 1% 0% Source: Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 Share of household income held by the top 1% of individuals Ratio of income at the 90th and 10th percentiles (90/10 ratio) 5 Inequality in context • Since the mid 1990s over much of the income distribution, from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile, inequality is stable – although this masks growing inequality for younger cohorts. • At the same time the welfare benefit system has had to do more work to maintain the incomes of individuals and families with low earnings – but will it continue to do so? • Note too the remarkable increase in inequality at the very top of the income distribution – in UK over two-thirds of the richest 0.1% of working-age adults work in ‘real estate, renting and other business activities’ or ‘financial intermediation’. • Wealth transfers across generations accentuate inequality – a growing proportion of younger individuals think they will receive inheritances, and are also those who already have the highest net wealth. Income Inequality by Age and Birth Cohort – UK Younger cohorts facing increasing inequality: 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 1930s 1940s 1950s 0.30 1960s 1970s 0.20 0.10 0.00 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 Age Source: Blundell and O’Dea (2014). Consumption Inequality by Age and Birth Cohort – UK Younger cohorts facing increasing inequality: 0.45 0.40 0.35 0.30 0.25 1930s 1940s 1950s 0.20 1960s 1970s 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 53 55 57 59 61 63 65 67 69 71 73 75 Age Notes: younger cohorts entering with much larger inequality than previous cohorts…. Source: Blundell and O’Dea (2014). .1 .15 .2 .25 .3 .35 .4 Consumption Inequality by Year and Birth Cohort - US 20 25 30 35 40 Born 1930s Born 1950s Source: Attanasio and Pistaferri (2014) 45 age 50 55 60 Born 1940s Born 1960s 65 70 C. Consumption – the final piece of evidence • Expenditure falls were deeper than in previous recessions. – Note that the start of the fall is coincident with the fall in GDP (not income). – Saving rates rise. • Unusually expenditure on consumer nondurables fell most – Especially among the young and to some extent among the middle aged, less for the old. – Temporary VAT reduction? © Institute for Fiscal Studies Non- and semi-durables 120 1980 Quarter before recession = 100 115 1990 110 2008 105 100 95 90 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Quarters since start of recession © Institute for Fiscal Studies Non- and semi-durables per head 120 Quarter before recession = 100 1980 1990 2008 115 110 105 100 95 90 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Quarters since pre-recession peak in GDP © Institute for Fiscal Studies 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Durables 140 1980 Quarter before recession = 100 130 1990 120 2008 110 100 90 80 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Quarters since start of recession © Institute for Fiscal Studies Percentage Change in Food Expenditure by centile: UK 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.02 0 2012-2009 1 4 7 10 13 16 19 22 25 28 31 34 37 40 43 46 49 52 55 58 61 64 67 70 73 76 79 82 85 88 91 94 97 -0.02 -0.04 -0.06 -0.08 -0.1 Notes: Understanding Society Source: Blundell and Etheridge, 2014 © Institute for Fiscal Studies 2012-2010 2010-2009 Percentage Change in Food Expenditure: 2010-2012 UK Change in Food Expenditure by Centile and HH type: 2010 to 2012 0.04 0.02 0 1 4 7 10 13 16 19 22 25 28 31 34 37 40 43 46 49 52 55 58 61 64 67 70 73 76 79 82 85 88 91 94 97 -0.02 All HHs Pensioners -0.04 w/o children with children -0.06 -0.08 -0.1 -0.12 Notes: Understanding Society Source: Blundell and Etheridge, 2014 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Prospects for the Economy • Younger workers and families are acting as if they expect a long-run, persistent fall in relative living standards – evidence from consumption and saving. • Real wages, productivity and investment have been slow to pick up – we can expect the pattern of lower real wages at the bottom to continue, but with fairly buoyant employment due to increased supply. • Most actual falls in real earnings have happened – but fiscal contraction implies large benefit cuts. • Appears the number of routine jobs near the middle of the earnings distribution has declined steadily – more jobs are now professional or managerial. In the 90s and 2000s wages grew fastest for high (and mid-skilled) occupations, and BA premium maintained. • Suggests longer term earnings growth will mostly come from highskilled occupations, with perhaps some at the very bottom. Employment shares of occupation groups Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) © Institute for Fiscal Studies Prospects for the Economy II • Still much to do in focussing on older workers in general, on return to work for parents/mothers, and on entry into work. • There are still some potential big gains here, – for example, as (higher skilled) women age in the workforce. • Growing complementarity between human capital and ‘on the job’ wage/productivity – little evidence of earnings progression for lower skilled and part-time workers, – Families with low skilled workers increasingly relying on the tax credit/benefit system and family labour supply. • Productivity and wages are closely related – but note the growing importance of pensions in the UK. • Productivity (and education) is still the key. Prospects for Reform • With growing earnings inequality there is increasing pressure on the tax and welfare system. – current systems raise revenue and redistribute inefficiently and unfairly. • Some potential big gains here with tax/welfare reforms to enhance earnings and address inequality (many from Mirrlees Review) – focus incentives on transition to work, return to work for women with children and on enhancing incentives among older workers, – reduce disincentives at key margins for the educated - enhancing working lifetime and the career earnings profile, – align tax rates at the margin across income sources to make taxation at the top more effective; e.g. dividends and capital gains – reform taxation of housing and wealth transfers. • But these reforms will not be easy! To quote Tim Besley, ‘high levels of inequality can skew the priorities of the state by limiting its capacity to act effectively’. But that’s all for now! Human Capital, Inequality and Tax Reform: Recent Past and Future Prospects Coase Lecture 2015 Richard Blundell* University College London and Institute for Fiscal Studies** Slides on my website http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctp39a/ Extra Slides 2008 Q1 2008 Q2 2008 Q3 2008 Q4 2009 Q1 2009 Q2 2009 Q3 2009 Q4 2010 Q1 2010 Q2 2010 Q3 2010 Q4 2011 Q1 2011 Q2 2011 Q3 2011 Q4 2012 Q1 2012 Q2 2012 Q3 2012 Q4 2013 Q1 2013 Q2 2013 Q3 2013 Q4 2014 Q1 2014 Q2 2014 Q3 2014 Q4 Change since 2008 Q1, £ billion Business investment has been very slow to pick up 15 10 Business investment 5 Household consumption: durable goods 0 -5 Household consumption: non-durable goods -10 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Earnings in line with productivity growth, particularly when using LFS measures of earnings Output per hour and worker compared to mean earnings in LFS (GDP deflated) since 2008Q2 Indexed to 100 in 2008Q2 105 100 95 Output per worker Output per hour worked Mean weekly earnings Mean hourly earnings © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Fig 2.7 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” 2014Q3 2014Q1 2013Q3 2013Q1 2012Q3 2012Q1 2011Q3 2011Q1 2010Q3 2010Q1 2009Q3 2009Q1 2008Q3 2008Q1 90 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Authors’ calculations using Labour Force Survey (ONS series MGRQ and MGRZ). 2014 Q3 2014 Q1 2013 Q3 2013 Q1 2012 Q3 2012 Q1 2011 Q3 2011 Q1 2010 Q3 2010 Q1 2009 Q3 2009 Q1 2008 Q3 2008 Q1 2007 Q3 2007 Q1 2006 Q3 2006 Q1 2005 Q3 2005 Q1 2004 Q3 2004 Q1 Self-employment as a share of total employment Self employment as a share of total employment 16% 15% 14% 13% 12% 11% Earnings for employees and the self employed 25% Percentage of employees / self-employed individuals Self-employed Employees 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Earnings (per week, April 2014 prices) © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Figure 2.14 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” Employment and unemployment rates since 2007 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Fig 2.1 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” 2014 Q4 2014 Q2 2013 Q4 2013 Q2 2012 Q4 4% 2012 Q2 70% 2011 Q4 5% 2011 Q2 71% 2010 Q4 6% 2010 Q2 72% 2009 Q4 7% 2009 Q2 73% 2008 Q4 8% 2008 Q2 74% 2007 Q4 9% Unemployment rate (age 16-64) (%) Unemployment rate (RH axis) 75% 2007 Q2 Employment rate (age 16-64) (%) Employment rate (LH axis) Real earnings indexed to 100 in 2008 Changes to real median weekly and hourly wages by sex 110 105 Male weekly earnings Male hourly earnings Female weekly earnings Female hourly earnings 100 95 90 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Notes: Results adjusted for methodological changes in 2011. Earnings observed in April of each year. Source: Cribb and Joyce (2015), calculations using Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. 2013 2014 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% Average EMTRs for different family types 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 Employer cost (£/week) Single, no children Partner not working, no children Partner working, no children Lone parent Partner not working, children Partner working, children Mirrlees Review (2011) Employer contributions to pension funds – in constant prices terms Source: Office for National Statistics Notes: Data for Q4 2012 is not yet published so has been estimated based on Q4 2011 to Q3 2012 data © Institute for Fiscal Studies Public sector – any Public sector – defined benefit Private sector – any Private sector – defined benefit Source: Fig 1 of Cribb and Emmerson (2014) “Workplace pensions and remuneration in the public and private sectors in the UK” 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1997 Percentage of employees in a pension scheme But recent falling membership of pensions schemes Particularly strong growth in private sector 8.0 Private (LH axis) Public (RH axis) 25.5 7.5 25.0 7.0 24.5 6.5 24.0 6.0 23.5 5.5 23.0 5.0 © Institute for Fiscal Studies Source: Fig 2.2 of Cribb and Joyce (2015) “Earnings since the recession” Public sector employment (million) Private sector employment (million) 26.0 NEET rate among young people 60% 50% 40% 18-21 GCSEs or above 18-21 without GCSE 30% 22-24 Degree level or above 22-24 GCSEs, A-levels, FE 20% 22-24 without GCSE 10% 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 0% Source: Blundell, Green and Jin (2014) Recent cohorts are also less likely to own a home Born 1963–67 Born 1973–77 Born 1983–87 Homeownership rate (%) 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Age Source: Figure 3.13 of Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality: 2014 © Institute for Fiscal Studies