Mentoring Project Report Learning and Teaching Scotland/New Teacher Center – May 2011

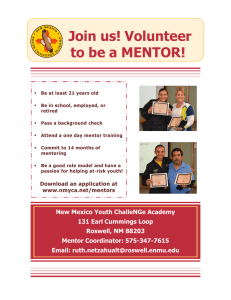

advertisement