Characterizing Transboundary Flows of Used Electronics: Summary Report

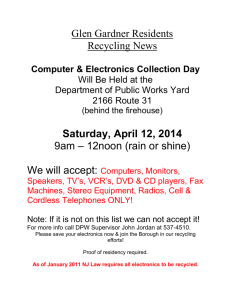

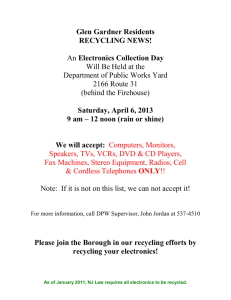

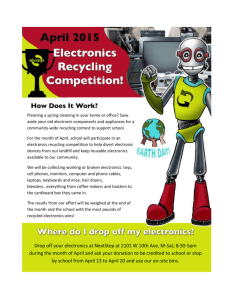

advertisement