Dumfries and Galloway Council May 2007

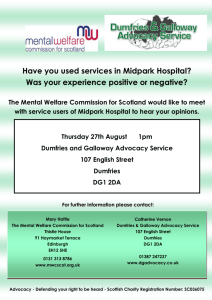

advertisement