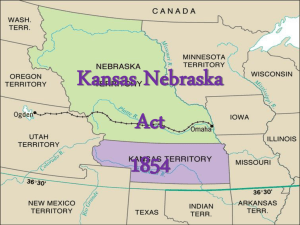

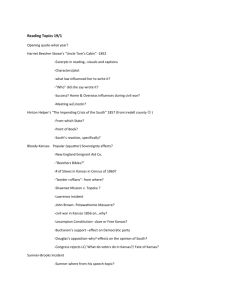

Perspectives K a n

advertisement