Participation Learning and

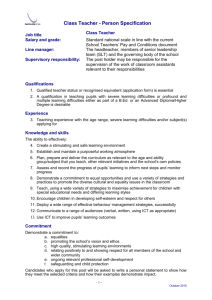

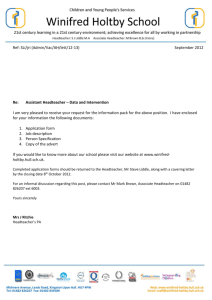

advertisement