PART A GUIDANCE FOR TEACHERS Including young people

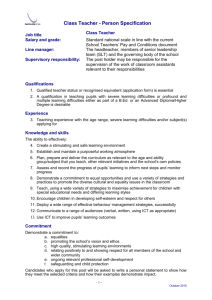

advertisement