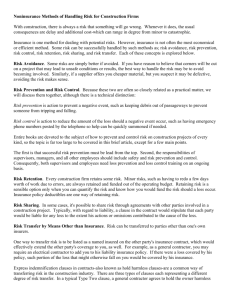

UIDP Federal Flow-Down Project Reference Guide Helping companies and

advertisement