Document 12950209

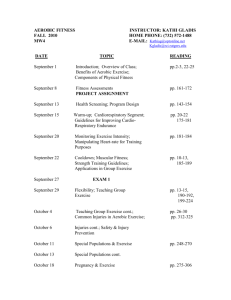

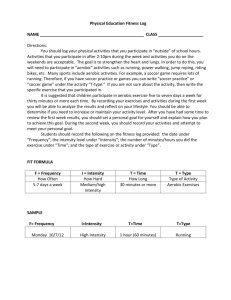

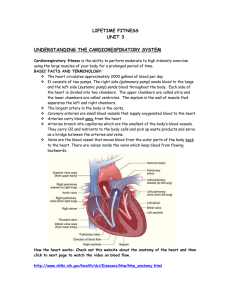

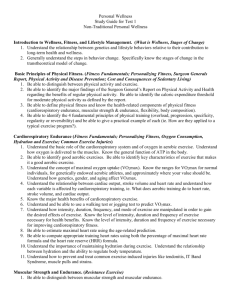

advertisement