Pathways to Sustainable Mediation: Challenges and Opportunities Spring 2015

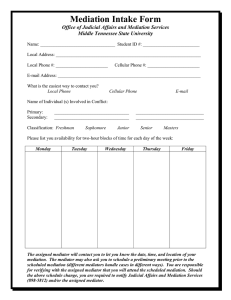

advertisement