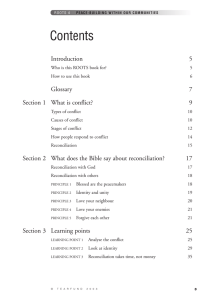

Reconciliation in Practice Reconciliation Programming

advertisement