DEVELOPMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL INDICATORS FOR TOURISM IN NATURAL AREAS: A Preliminary Study

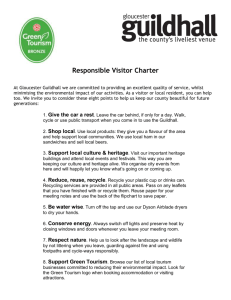

advertisement