Was Velázquez' Meninas the first Cubist painting?

advertisement

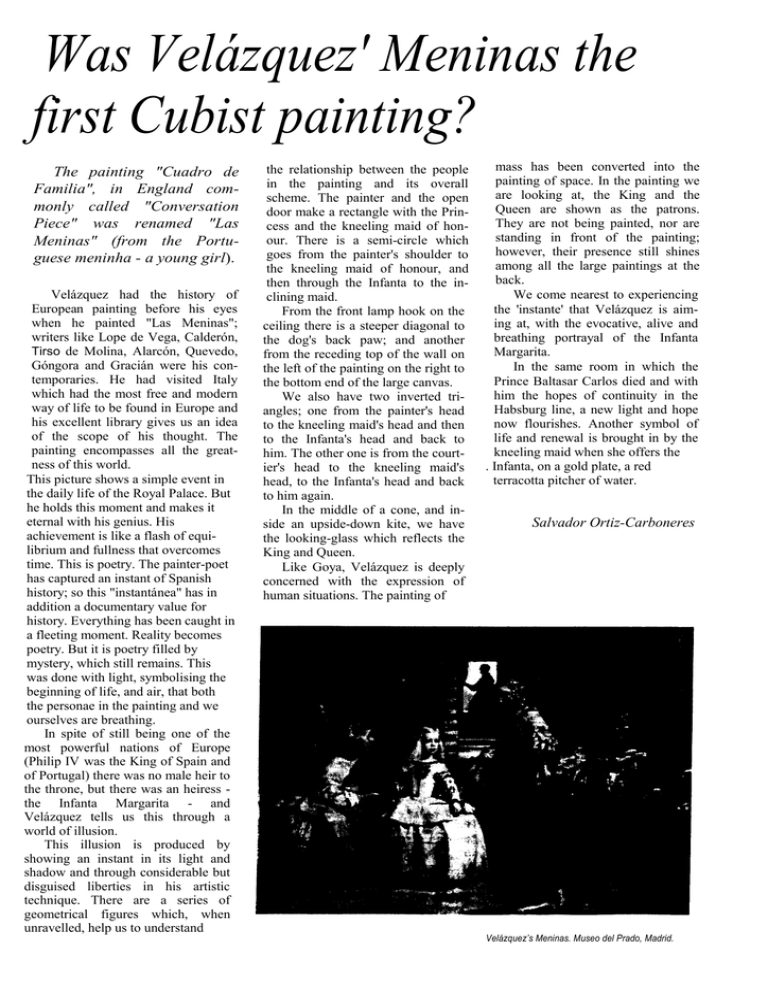

Was Velázquez' Meninas the first Cubist painting? The painting "Cuadro de Familia", in England commonly called "Conversation Piece" was renamed "Las Meninas" (from the Portuguese meninha - a young girl). Velázquez had the history of European painting before his eyes when he painted "Las Meninas"; writers like Lope de Vega, Calderón, Tirso de Molina, Alarcón, Quevedo, Góngora and Gracián were his contemporaries. He had visited Italy which had the most free and modern way of life to be found in Europe and his excellent library gives us an idea of the scope of his thought. The painting encompasses all the greatness of this world. This picture shows a simple event in the daily life of the Royal Palace. But he holds this moment and makes it eternal with his genius. His achievement is like a flash of equilibrium and fullness that overcomes time. This is poetry. The painter-poet has captured an instant of Spanish history; so this "instantánea" has in addition a documentary value for history. Everything has been caught in a fleeting moment. Reality becomes poetry. But it is poetry filled by mystery, which still remains. This was done with light, symbolising the beginning of life, and air, that both the personae in the painting and we ourselves are breathing. In spite of still being one of the most powerful nations of Europe (Philip IV was the King of Spain and of Portugal) there was no male heir to the throne, but there was an heiress the Infanta Margarita - and Velázquez tells us this through a world of illusion. This illusion is produced by showing an instant in its light and shadow and through considerable but disguised liberties in his artistic technique. There are a series of geometrical figures which, when unravelled, help us to understand the relationship between the people in the painting and its overall scheme. The painter and the open door make a rectangle with the Princess and the kneeling maid of honour. There is a semi-circle which goes from the painter's shoulder to the kneeling maid of honour, and then through the Infanta to the inclining maid. From the front lamp hook on the ceiling there is a steeper diagonal to the dog's back paw; and another from the receding top of the wall on the left of the painting on the right to the bottom end of the large canvas. We also have two inverted triangles; one from the painter's head to the kneeling maid's head and then to the Infanta's head and back to him. The other one is from the courtier's head to the kneeling maid's head, to the Infanta's head and back to him again. In the middle of a cone, and inside an upside-down kite, we have the looking-glass which reflects the King and Queen. Like Goya, Velázquez is deeply concerned with the expression of human situations. The painting of mass has been converted into the painting of space. In the painting we are looking at, the King and the Queen are shown as the patrons. They are not being painted, nor are standing in front of the painting; however, their presence still shines among all the large paintings at the back. We come nearest to experiencing the 'instante' that Velázquez is aiming at, with the evocative, alive and breathing portrayal of the Infanta Margarita. In the same room in which the Prince Baltasar Carlos died and with him the hopes of continuity in the Habsburg line, a new light and hope now flourishes. Another symbol of life and renewal is brought in by the kneeling maid when she offers the . Infanta, on a gold plate, a red terracotta pitcher of water. Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres Velázquez’s Meninas. Museo del Prado, Madrid.