community A U A U

A

M E R I C A N

U

N I V E R S I T Y

A N N U A L R E P O RT

2 0 0 5 – 2 0 0 6

A U IN THE

community

TABLE OF CONTENTS

From the Chairman of the Board of Trustees

From the Interim President

Introduction

Creating Opportunities for Learning

Volunteering in Our Community

Sharing Our Resources

From the Vice President of Finance and Treasurer

Financial Statements

University Administration

Board of Trustees

14

20

24

25 inside back cover inside back cover

4

6

2

3

2 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Dear Friends:

This annual report describes a financially strong university whose mission touches the citizens of the nation’s capital and surrounding region in powerful ways. AU students, faculty, and staff participate in an array of educational programs that improve the quality of life for area residents, sharing our knowledge to benefit others through teaching, tutoring, and doing—and in the process, learning about

Washington, D.C., and environs.

In addition to the teaching-learning dynamic, AU makes our campus and named facilities available for community benefit. The Katzen Arts Center makes a strong statement regarding AU’s role as a community resource. Bender Arena hosts graduation ceremonies for our neighboring D.C. public high school; the

Jacobs and Reeves athletics fields and Greenberg Track help local businesses raise funds for worthwhile causes; and our Kay Spiritual Life Center has long served as a community gathering spot.

These opportunities exist because of the strong public service ethic of AU students, faculty, and staff and the facilities made available by generous friends and far-sighted donors.

American University has always embraced a strong service-oriented mission in all that we do. It’s great to see how this legacy continues.

Sincerely,

Gary Abramson

FROM THE INTERIM PRESIDENT

Dear Friends:

Each year in the pages of our annual report, we describe key aspects of our educational mission that help make American University distinctive. Indeed, to complement our curriculum breadth, global focus, and the national and international reach of our student and alumni base, a strong distinction is the vibrant role we play in and around the nation’s capital city.

AU’s commitment to Washington, D.C., can be seen in myriad ways, such as the teaching and learning opportunities that cater to the area’s citizens and businesses, the campus facilities utilized by the community for worthwhile endeavors, and the hours of volunteer assistance given by students to those in need.

When freshmen first step onto campus, they are exposed to their host city through the Freshman Service

Experience program, in which some 40 percent of new students take part. But that is only the beginning.

The pages of this annual report demonstrate numerous other ways in which American University students, faculty, staff, and programs interact in an ongoing basis with the District and its people.

As American University educates its students for the twenty-first century, a vital part of that education comes from lessons learned and experiences gained in Washington, D.C., and through the beneficial partnership that has grown between AU and its host city.

Sincerely,

Cornelius M. Kerwin

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 3

W H AT D O E S I T M E A N T O B E PA R T O F A C O M M U N I T Y ?

It’s more than an address. It’s a way of participating in the life of the place that you call home. It’s welcoming neighbors to events they’ll enjoy, sharing useful skills and knowledge, and volunteering in ways that make the community a better place for everyone.

4 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

This year, the opening of the Dr. Cyrus and Myrtle Katzen Center for the Arts has thrown a revealing spotlight on the place of AU in its community. The striking new facility has already welcomed some 20,000 visitors, including neighbors who come to listen to artists’ talks, school children from nearby Horace Mann and Janney Elementary Schools, and seniors from the Knollwood military retirement center.

The concerts that draw applause from music lovers sometimes feature well-known musicians who happen to live in the neighborhood, while about half of the visual artists whose work has been exhibited so far hail from the Washington area. The docents who guide the tours are local volunteers. Even the embassies which make up such a prominent part of the

Washington community have been enthusiastic participants in the Katzen’s programming.

The Katzen has been a major newsmaker since its doors opened in mid-2005, but the campus has seen other newsmakers as well: Jimmy Carter, Bob Woodward, Newt Gingrich,

Madeleine Albright. All have spoken on campus and drawn substantial crowds from across the Washington area.

AU and its people also help to make the community a better place to live and work in a host of quiet ways. Opportunities for professional development abound. Close to 1,000 teachers from District of Columbia schools have participated in programs to enhance their teaching skills and content knowledge. Nonprofit organizations have enhanced their ability to communicate with new media tools at an AU institute on strategic communication.

Students and faculty are active in bringing their knowledge and skills into the community, from helping to construct a playground in the Columbia Heights neighborhood to presenting chamber music programs for low-income children.

Law students take time to educate young people in 15 D.C. public high schools about their constitutional rights. Law clinics handle over 500 cases a year, helping a range of clients that include refugees seeking political asylum, farmers’ markets, and workers’ cooperatives. Scores of law students also did pro bono work over the past year for such organizations as the Whitman-Walker Clinic, Children’s Law Center, and Asian Pacific

American Legal Resource Center.

History students have worked to save a historic home on Dupont Circle and to help preserve the history of area communities from Eastern Market to Adams Morgan to Anacostia. Kogod students share their time and budding business knowledge with small nonprofits and lowincome taxpayers. AU students start community-oriented nonprofits and work with homeless shelters, community centers for seniors, and other local organizations.

Even the university buildings themselves play a role in the community, since facilities are regularly used for fund-raisers that bring tens of thousands of dollars to such causes as the

Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the Washington Animal Rescue League.

Every year, thousands of AU students, faculty, and staff volunteer in the Washington community, and thousands of Washingtonians come to campus to experience what AU has to offer. AU and its community. They’re part of each other.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 5

C R E AT I N G O P P O R T U N I T I E S F O R

learning

Students aren’t the only ones who discover new ideas at AU. This year, some 20,000 visitors enriched their lives with art at the long-awaited Katzen Arts Center. Washingtonians flocked to hear speakers like Madeleine Albright, Bob Woodward, and Gen. Wesley Clark, or to attend such programs as the Visiting Writers Series, which brought novelists and poets to campus. People came to

AU to learn, and the people of AU went out into the community to share their knowledge. From conferences to classes, from the ideas of prominent newsmakers to the visions of experimental artists,

AU offered endless opportunities to its neighbors.

6 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A R T S C E N T E R D R AW S C R O W D S

For years, the people of Washington watched as the Katzen Arts Center rose at Ward Circle, and they waited curiously for its doors to open. So it’s not surprising that some 20,000 visitors poured into the AU Museum at the Katzen Arts Center during its first year of operation.

They came to see 17 shows, featuring hundreds of artists, about half of them from the Washington area. They came to listen to artists’ talks and sign up for tours. Sixty came to volunteer as docents.

As for artists, they’ve been so eager to show in the high-profile space that some 250 proposals fill four boxes in museum director Jack Rasmussen’s office. And it’s not just artists who propose shows. Embassies interested in highlighting their cultural riches also approach the Katzen with ideas for shows.

There’s no question it has proven to be a good venue. Every day is a tour day at the Katzen. “We give a tour every day, either formal or informal,” said museum director Jack Rasmussen.

Among the thousands of visitors over the past year were children from nearby Horace Mann and Janney

Elementary Schools and summer campers from down the street at the National Presbyterian School. There were retired military officers and family members from the Knollwood retirement community and visitors from the

Kennedy Center, the Corcoran, the Hirshhorn, and the Smithsonian.

The Katzen was one of the first stops in the U.S. for the wife of the prime minister of Israel during a brief state visit of Washington. On a single day in April, 20 ambassadors’ wives came to see and learn about the shows.

Private tours have even been auctioned off as fund-raisers for local schools.

For Roxana Martin of Bethesda, the Katzen has offered a chance to realize a longtime dream. The 1982 AU graduate, who is also a Katzen docent, had long wanted to get involved in art. So she enrolled in the first class offered at the museum, which gave students a chance to curate their own shows. It was a chance, she said, “to enter the art world by the big door.”

The Katzen’s doors have already opened the world of art to thousands. And it’s just the beginning.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 7

T E A C H I N G T H E T E A C H E R S

AU’s education classrooms aren’t filled only with the teachers of the future. Every year they’re also filled with practicing teachers who come to expand their knowledge, strengthen their skills, and become models of top-notch teaching in their own schools.

Some of them are teachers in the D.C. school system who spend their summers as part of a program called Strengthening the Teaching of American History, in which they not only enhance their knowledge of such subjects as colonial history but learn innovative ways to communicate that knowledge. Each year, about 45 teachers have participated.

The halls of AU are also full of D.C. teachers working to meet the exacting standards of national board certification under the Alliance for Quality Urban Education (AQUE). Sponsored by a $6.4

million grant, some 240 teachers have entered the schools, another 100 have worked on board certification, and some 150 have taken free content courses.

The same grant brings educators and experts together for “think tanks” on how to support teachers in their professional development and, ultimately, boost the academic achievement of students.

Another project draws to AU a number of people who have just made a big decision. They may have had a successful career—as a lawyer, perhaps, or an engineer—but now they want to become a teacher. Already, around 240 professionals from other fields have been licensed as teachers through a program known as Transitioning Our Provisional Stars (TOPS).

There are smaller programs, as well. And some of them can have a big impact. For instance, a core group of 15 art teachers have returned for three summers running for a professional development program, Theory into Practice, that not only enhances their studio skills but helps them to integrate math and architecture into teaching. They’re now putting together a curriculum guide for the D.C.

Public Schools based on what they’ve learned at AU.

In a few years, there may not be many teachers in Washington who haven’t taken courses at AU, quips Mary Schellinger, assistant dean of the School of Education, Teaching, and Health.

Through its many research programs, projects, and grants, AU is having an impact on the Washington community that goes far beyond its full-time students. It is making a difference for the city’s children.

8 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

I M A G I N I N G A B R I G H T E R F U T U R E

Gail Humphries Mardirosian has made it her mission to “cultivate the artist in every child.”

Ten years ago, Mardirosian, chair of AU’s Department of Performing Arts, founded

Imagination Quest, a program aimed at strengthening literacy skills among at-risk children through the arts. Since its inception, Imagination Quest has reached more than 2,000 students, 1,450 teachers, 325 parents, and 70 school principals from the Washington metro area, California, and New Hampshire.

“All the research indicates that if a child doesn’t learn to read by fourth grade, he’ll constantly be at a disadvantage,” said Mardirosian. “We have to make a difference one child at a time, and this project allows for that to happen.”

Using a children’s story, such as Eleanor Estes’s The Hundred Dresses, Mardirosian and her team of 20 artists and educators use dance, music, sign language, poetry, puppets, pantomime, and videos to help youngsters sharpen skills, from vocabulary and reading comprehension to math and science.

“The program works because it offers such a wide variety of options, which means it addresses a wide variety of students,” said Florine Bruton, principal of Anacostia’s Mildred

Green Elementary School, with whom the program has partnered for the last few years.

“Some students learn by hearing, some learn by moving, some by seeing . . . Imagination

Quest helps us reach students through all these different avenues. It helps us reach those students we might not reach otherwise.”

Mardirosian is developing a DVD and book for teachers; also, she’s leading a graduate course for D.C. teachers, focusing on arts-based methods.

“Slowly but surely this idea of teaching through the arts is expanding,” she said. “But if you look at who we’re reaching, it’s really expanding exponentially. Just think, for every teacher that we reach . . . imagine the number of students that they will reach.”

L E A R N I N G N E V E R S TO P S

Learning certainly doesn’t stop when a young undergraduate adjusts the tassel on his or her mortarboard on graduation day. The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at American University has understood this for a quarter-century, during which time it has quenched people’s thirst for knowledge through continuing education classes. Last year more than

550 people of all ages took classes ranging from politics to philosophy to music. More than 50 noncredit courses were offered during two, 10-week semesters. In addition, the institute offers a free lecture series that is open to public. In the past, the series has attracted such big-name speakers as journalists Bob Woodward and Steve Roberts.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 9

I N S T I T U T E H E L P S N O N P R O F I T S C O M M U N I C AT E

Nearly 40 nonprofits, including Amnesty International and Oxfam America, took a lesson in online communication from one of the Web’s most successful publishers, washingtonpost.com, during the 2006 Institute for Strategic Communication for

Nonprofits sponsored by AU’s School of Communication.

While washingtonpost.com executive editor Jim Brady, SOC ’89, shared the strategies that have gained the newspaper site 9 million readers, the institute also brought in other industry experts to discuss how to use electronic media to connect with and mobilize an audience. “It’s a big help to us to see how an established media organization has integrated the various features of the Web to connect with and build a community,” said Joan Ochi, marketing director of Global Giving, a local nonprofit that funds social and environmental projects throughout the world.

Because it was held in conjunction with the SilverDocs documentary film festival, sponsored by the American Film Institute and Discovery Channel of Silver Spring,

Maryland, the nonprofit institute’s 60 participants had the opportunity to network with documentary filmmakers about the emerging role of video in nonprofit communications.

“All of the other participants I met with were in the same boat,” said Ochi. “We’d all heard of these tools but didn’t really know how to use them. Now we can see the potential for them in our own work.”

Now in its fourth year, the Institute for Strategic Communication for Nonprofits was launched in 2003 by SOC professor Maria Ivancin and SOC dean Larry Kirkman.

“The values of the university and the School of Communication—human rights, social justice, and democracy—inspire our commitment to building the nonprofit sector’s communication capacity,” said Kirkman.

1 0 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A LO C A L R A D I O V O I C E I N YO U R LO C A L E

The audience at Arena Stage in Southwest Washington on this night was raptly attentive, and it wasn’t hard to discern why. The topic during radio host’s Kojo Nnamdi’s latest foray out of his WAMU studio onto the front lines—the future of the neighborhood many of them call home—was of the utmost importance to the people in the Kreeger Theater.

As the crowd watched, listened, and participated in a live taping of the Kojo Nnamdi Show that would air two days later, it was clear that yet again “Kojo in the Community,” Nnamdi’s traveling radio program series, had struck a nerve.

“I moved to Southwest in 1976,” said community activist Thelma Jones, one of two panelists on stage for the broadcast. “I saw a beautiful oasis. Development does need to occur. I’m not against development. But I am against disrupting people’s lives. When the fabric of this community changes, that’s going to disrupt people’s lives.”

Throughout the hour, residents and experts discussed how the mistakes of the past could be avoided in the coming years, when a massive revitalization effort in the area promises to dramatically alter the neighborhood. The hot—but not heated—dialogue was typical of the series, which previously visited Laurel and Bethesda, Maryland; Falls Church, Virginia; and the Columbia Heights and Anacostia sections of the District.

“You’re the reason why we’re here,” Nnamdi told the audience before the broadcast. “Yours are the voices we’d like to hear on the radio.”

It was that desire to get even closer to the heart of the issues he routinely discusses on his daily political, news, and talk show that first led Nnamdi out into the community for a taping in

2001. The series was anointed “Kojo in the Community” in 2003, but a lack of funding halted the forums until 2006, when a grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation reestablished it.

“I welcome the chance to get out of the studio and into the community,” said Nnamdi, who’s been a local broadcaster for more than three decades. “These forums encourage citizens to discover new points of view and offer everyone a chance to be part of the dialogue.”

L AW S T U D E N T S B E C O M E C O N S T I T U T I O N A L L E A D E R S

You may think that no one benefits more from the Washington College of Law’s Marshall-Brennan Fellows Program than the thousands of D.C. public school children who learn the ins and outs of the U.S. Constitution from WCL students. Think again, this time heeding the words of WCL student Laura Israel, who taught students at Paul Public

Charter School in Northwest Washington.

“I learned a lot more about individual rights than I would have in a normal course, because when you teach a subject you really have to absorb it,” Israel said. “I’m definitely a different person for having known these kids.”

More than 50 WCL students spent the entire academic year teaching 20 classes in 15 D.C. public high schools. The program, which began in 1999, is named in honor of late U.S. Supreme Court justices Thurgood Marshall and

William Brennan. Led by WCL professors Jamin Raskin and Steve Wermiel, the curriculum aims to educate young people on their constitutional rights by teaching them about the document and landmark Supreme Court decisions.

“We would present them with an issue, and the highlight was to see them put together an argument and leave emotion out of it,” said Nisha Thakker. “When they were finally able to do that, it was one of our biggest breakthroughs.”

AU’s program has served as a model for similar ones being hatched at law schools across the country. The law school students who commit to it must dedicate countless hours to what almost always is a highly challenging endeavor, yet the words of two students leave no doubt about their belief in the program.

“I think it’s one of the best programs AU has to offer because it can teach a law student how to stop being a law student for a minute and focus on the big picture,” Thakker said.

“It shows you that in your career you can always make time to do something you’re passionate about even if it’s not your primary thing,” Israel added.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 1 1

R E N O W N E D V O I C E S H E A R D O N C A M P U S

Year after year, American University draws some of the world’s most extraordinary individuals to campus to share their experiences, observations, and stories—and the majority of these lectures are open to the public. Last year an all-star lineup, including diplomats, politicians, journalists, comedians, and even a former president, were among the throngs of notable people who delivered speeches to students, faculty, staff, parents, neighbors—anyone interested in enriching their mind.

Here’s a taste of what they had to say.

Barack Obama , Democratic senator from Illinois

“I believe a serious conversation about reform would be one that would be good for this town to have in the coming months. Instead of meeting with lobbyists, we should meet with the 45 million Americans without health care. All these people do to influence the process is cast their vote. In our democracy, it’s all they should have to do.”

Madeleine Albright, former secretary of state

“It’s not that I lacked ambition, it’s that I’d never seen a secretary of state in a skirt.”

Newt Gingrich, former speaker of the House

“Right now, we may be at the end of a 40-year cycle of bitterness.

I’ve spent enough of my life fighting. I’d like to spend some of it constructing, and I think the country feels the same way.”

Bob Woodward, journalist

“In my business, we’re trained to doubt. I have to be the calcium in the backbone.”

Frances Fragos Townsend,

1 2 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y homeland security advisor to President Bush

“We heard much of the great failures during Hurricane Katrina, and there is much we want to do to improve the government’s response to such disasters. But let me share with you some of the facts you probably have not heard. The Coast Guard had 33,500 rescues, or six times the number of rescues it had in 2004. As of October 15, FEMA has provided $3 billion to 1.6 million people. I am humbled to call those in public service my colleagues.”

Dick Gregory, comedian, author, activist

“When I stand here tonight and tell you that no one before on this planet has made progress like black folks in the last 40 years, I don’t have to be validated. I was in Mississippi taking [Dr. Martin Luther]

King’s word for it. Who could have thought that standing here 45 years later the head of Mississippi’s state troopers is a black man?

King knew where it was going.”

Jimmy Carter, former president

“I would like to see the United States of America be looked upon throughout the world as the preeminent nation that espouses peace, not preemptive war. I would like for our country to be looked upon as a symbol of democracy and freedom so that the electoral system in America, the example of democracy, is without blemish. I would like to see America be looked upon as the nation on Earth that holds highest the banner of basic human rights, and I would like to see our country be looked upon as the most generous nation on Earth.”

Joseph Wilson, former ambassador

“The first line of my obituary used to read, ‘Last American diplomat to have met with Saddam Hussein before the Gulf War.’

Now of course it reads, ‘Husband of the first American spy ever to have her identity compromised by the American government.’”

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 1 3

V O L U N T E E R I N G I N O U R

community

Thirteen thousand hours is just a start. When AU’s new freshmen arrive a week early for three days and 13,000 hours of cleaning parks, feeding the homeless, and volunteering with local organizations, they get so hooked on helping that many continue to volunteer throughout the year. The 16-year-old

Freshman Service Experience, said to be the largest program of its kind in the nation, is only one of many ways AU reaches out. Law students devote long hours of pro bono work to the Whitman-

Walker Clinic, Children’s Law Center, and numerous other groups. Chamber musicians bring their melodies to low-income children. Students work with seniors, tutor in Washington’s schools, and share AU’s positive energy with the larger community.

1 4 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

P R O M OT I N G PA S S I O N S

Before they even crossed the stage and collected their diplomas last May, 18 graduate students had already gotten a taste of life as public relations executives.

The students, enrolled in SOC professor Gemma Puglisi’s Public Communication Practicum class, were tasked with crafting a promotional campaign for a local nonprofit or community organization—groups often strapped for both volunteers and cash.

“It’s our responsibility as professors to not only give students a very strong education, but to also prepare them for the real world and corporate America,” said Puglisi. “I wanted them to be their own PR firm, find a client they’re passionate about, and—in 13 short weeks—show them what they can do.”

The students, who worked with homeless shelters, a community center for seniors, and Habitat for

Humanity, among other organizations, wrote press releases, worked on fund-raising campaigns, and organized events.

“Some of these kids really made a difference for these organizations. If people had to pay for this publicity, it would’ve cost them a lot of money,” said Puglisi. “It gave the students a real sense of responsibility and a tremendous sense of satisfaction.”

Kevin Brosnahan worked with Central Union Mission, a Washington homeless shelter, soup kitchen, and food bank. Brosnahan, who worked six to eight hours each week, reworked the mission’s press materials and developed strategies for generating media coverage.

The project, Brosnahan said, “helped me to realize that almost every organization can benefit from better communications.”

“The Central Union Mission does a great deal of important work,” he continued, “but it was important for them to tell their story in a more effective way.”

This wasn't the first time Puglisi and her students partnered with members of the community. Last year, Washington restaurateur Franco Nuschese, owner of the popular Georgetown eatery Cafe Milano, turned to 18 seniors in Puglisi’s Public Relations Portfolio class to get the word out about his new restaurant, Sette Bello.

The students created a national PR campaign for Sette Bello, which opened in Arlington, Virginia, in

October 2005. By the project's end, the students reported more than 19 million “impressions,” which represent the total circulation of the radio programs, newspapers, magazines, and Web sites they targeted. Had Nuschese paid the students for their work, they would have presented him with a bill for

$151,000.

“This project [gave] the students the opportunity to apply everything they learned,” said Puglisi.

“I hope it opens doors for them.”

L E A D E R S H I P O N T H E S Y L L A B U S

Leadership and engagement in Washington is part of the curriculum at the School of International

Service (SIS) from the beginning. The first semester of freshman year finds new students enrolled in a class called Leadership Gateway.

In addition to their course work, students are encouraged to interact with the Washington community by volunteering, observing Congressional hearings, and attending events at Washington think tanks and the U.S. State Department.

“It provides a vital foundation for the (freshman) class in terms of AU’s and SIS’s tradition of service and excellence in leadership,” says Nanette Levinson, associate dean for academic affairs at SIS, who often teaches the class. “This is a rigorous and exciting foundation for what the school and university represent.”

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 1 5

S AV I N G H I S TO R Y

Kathy Franz opened her morning paper and learned that a treasure was slipping away. If $250,000 couldn’t be raised within two weeks, the bank would foreclose on the Heurich House, the most fully intact Victorian house in the country. Since 1894, the 31-room mansion had graced Dupont Circle as a virtual time capsule of the Gilded Era, still furnished with its original plush carpets, luxurious sofas, carved mantels, and gilded bathtubs. But it soon could end up as a tony restaurant or posh condominium.

Franz had something to offer beyond a sigh and a shake of the head. As director of AU’s graduate program in public history, she could muster a zealous band of graduate students who shared a passion for Washington’s history. By the end of the week, they’d be hosting the first of two fund-raisers, complete with music by an AU quartet.

For AU’s public history students, the city is more than a classroom. It’s a place where they uncover hundreds of stories and then give those stories back to the community. The program’s role in the community, as Franz sees it, is “to really help community researchers interpret and present their own history.”

Over the past year, they’ve helped community historians research the photographic history of Eastern Market and build an exhibit for the market’s 200th anniversary. They’ve worked with the Anacostia Museum to develop public programming for an exhibit on high-school bands in Washington, D.C., and music education in the African-

American community. They’ve worked on a Web site, Teaching with Historic Places, supported by the Park Service.

In the case of the Heurich House, they helped the community to save its history. Built by a German immigrant who had made a fortune as a brewer, the mansion had changed little since its heyday, in part because brewer Christian

Heurich, who lived to the age of 102, would never permit anyone to change the furnishings selected at the turn of the century by his wife.

But it had fallen into hard financial straits. Once the home of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., the landmark was on the brink of being sold for its debts when the news got out, and the community came to help.

More than 1,700 people flocked to the fund-raisers and tours hosted by AU students, which raised more than

$100,000. Because of the strong community response, the deadline to pay off the mortgage interest was extended and, with the help of a $500,000 line item in the city budget, the immediate threat warded off.

There’s still work to be done to save the house for the future. And that is only a small part of the work that AU’s public history students will be doing around the city. For these students, working with the community is part of the program.

B I N G O W I T H A T W I S T

Bearing bingo cards and snacks, 50 students celebrated Martin Luther King

Jr. Day last January with seniors at the

Washington Center for Aging.

The group played black history bingo with special cards featuring photos of influential African Americans, including

Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela, Sojourner

Truth, and Duke Ellington. Instead of calling out “B-I-N-G-O” to claim their prize, seniors yelled “M-L-K-J-R.”

1 6 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

T U R N I N G T H E PA G E

Thirty percent of Washington third graders fail standardized reading tests. As part of the D.C. Reads program, 230 AU students are working with youngsters in Anacostia and

Columbia Heights to improve that statistic.

The college tutors spend four to six hours per week with the pupils, who range from kindergarten through eighth grade.

“My students make me feel special, and I like to think that

I make them feel special too,” said sophomore Angela Nagy, who works with students at Garfield Elementary. “It is a simple exchange of everyday smiles, compliments, corrections, and hugs that make me so happy I chose to become a tutor.”

L E N D I N G A H A N D

Wielding shovels and wearing work gloves and smiles, 491 students fanned out across the city in August as part of AU’s Freshman Service Experience (FSE).

Now in its 16th year, FSE brought together students to volunteer at 45 sites throughout the

Washington area, preparing meals, rebuilding homes, moving donated furniture, and working with children. In 2005, the freshmen logged about 10,000 community service hours at places like Wilson High School, where they helped replant a rose garden, and Sarah’s Circle, where students assisted the elderly with craft projects and served up a barbecue lunch.

During the three-day project, students were also encouraged to learn the history of the neighborhood where they were working, eat at a local restaurant, and explore the cultural and socioeconomic issues facing community members.

“We don’t just want students to type or paint, we want students to connect with the burning issues facing these residents,” said Marcy Campos, AU’s director of community service. “With that exposure, we’re hopeful that they’ll be committed to doing more service projects during their four years at AU.”

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 1 7

A LITTLE MONEY MAKING A BIG DIFFERENCE

Born when a student was inspired to raise money to renovate a dilapidated neighborhood playground in

Washington, the Eagle Endowment has become a permanent fixture at AU. The fund distributes small but important grants to students who hope to make a difference—however small—in their community.

This year, Monique Toussaint was awarded $1,000 to produce a sports career day for Kids 2 College, a nationwide nonprofit that goes into schools to educate kids about the benefits of attending college. A second award was divided among three groups. Jes Therkelsen was awarded $750 to make a film about a couple in

Anacostia who run a community art gallery, Sarah

Haney was awarded $500 on behalf of the crew team to clean up the boat house in Anacostia, and Kristen

Apa was awarded $250 to start an arts program at a children’s homeless shelter.

The Eagle Endowment is proof that a little bit of money can go a long way.

T H E B U S I N E S S O F H E L P I N G OT H E R S

Well-rounded professionals need to know more than just the ins and outs of making money. They also must understand that their expertise can help those less fortunate.

Kogod School of Business’s Washington Initiative program teaches that lesson to dozens of students each year, in the process lending a helping hand to

Washington organizations dedicated to community service. This past year 33 students raised $1,500 for the Hoop Dreams Scholarship Fund, which helps send Washington high school students to college. In the spring, students volunteered with Community

Tax Aid Inc., which offers free tax preparation and representation services for low-income taxpayers in the Washington metropolitan area.

A C T I V I S T A S P I R AT I O N S

The students in Katharine Kravetz’s Transforming Communities seminar arrive in Washington from all corners of the country with activist aspirations and a desire to better their own neighborhoods.

For these two dozen students in AU’s Washington Semester program, the city quickly becomes their classroom.

The students spend four hours a week working at a local nonprofit, school, or community organization. Students have volunteered at the

D.C. Employment Justice Center and charter schools, including the

Maya Angelou School and the Thurgood Marshall Academy.

“My goal is for them to understand how nonprofits work and whether nonprofits and the volunteers they use can make a significant dent in the problems communities confront,” said Kravetz.

“We’re in a period in this country where we expect nonprofits to do a lot of the things that government was doing 30 or 40 years ago,” she continued. “I want students to really think about what the appropriate role of a nonprofit is and how, at the grassroots level, they can affect poverty and social change.”

Over the last six years, Kravetz’s students have logged thousands of hours at D.C. organizations. The hope, she said, is that when students return to their home colleges across the country, they continue to volunteer.

“Students come away from the semester with amazing stories—stories of helplessness and of hope,” Kravetz said. “They also come away with a better sense of purpose.”

1 8 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

C H A L L E N G I N G S T E R E OT Y P E S

Each year, the 35 exemplary freshmen admitted to the School of Public Affairs’s Leadership Program spend 100 hours each volunteering at community organizations. The goal of the project is to help students challenge their own stereotypes and prejudices and develop a keener sense of empathy, director Sarah Stiles explained. “By working with people less fortunate, they are able to put a face to the issue,” she said.

Students spend 50 hours each semester working with such groups as the National Coalition for the

Homeless, Miriam’s Kitchen, My Sister’s Place, and the YMCA Calomiris Program Center, which oversees a career development program for teens. The freshmen have also volunteered at D.C.’s

Brightwood and Mildred Green elementary schools.

The students must design and implement a program or event that meets the organization’s needs.

Last year, for example, students hosted an outdoor education fair for fourth graders at Brightwood

Elementary. They taught the youngsters about conservation, the environment, and the importance of playing outdoors. After a spirited game of kickball, the kids made their own terrariums with plastic bottles, dirt, and seeds.

Throughout the four-year program, the 120 participants explore leadership theory, develop conflict resolution techniques, and hone their public speaking skills. Program graduates have gone on to

Teach for America, the Peace Corps, and top graduate programs at Harvard and Princeton.

“Students come away from the program with a greater sense of self-awareness and social awareness,” said Stiles. “They feel a sense of joy and satisfaction when they know they have helped someone.”

U N S U N G H E R O E S

Charise Van Liew, who cofounded Facilitating Leadership in Youth (FLY) in

1999 as an AU freshman, was honored by the Community Foundation for the

National Capital Region. One of six recipients of the 2006 Linowes Leadership

Award, Van Liew was praised for her creativity, vision, and leadership.

The nonprofit organization helps 40 Anacostia youth achieve their educational goals and develop their artistic and leadership skills. FLY began as a student club before Van Liew, James Pearlstein, and Amy Hendrick incorporated the organization in 2002.

Today, 50 AU students support FLY youth on a weekly basis through tutoring, mentoring, and arts programs.

“It’s great to see so many people working together to accomplish our mission of supporting people east of the river,” said Van Liew. “D.C. is a relatively small city and its residents can often be overlooked, so it’s important to connect students with the people in Anacostia.”

The Linowes Leadership Award, established in 1997, recognizes the efforts of

“unsung heroes” working to improve communities throughout the Washington area. Van Liew said the $5,000 she received in grants from the Community

Foundation will go toward FLY’s mentoring and tutoring programs.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 1 9

S H A R I N G O U R

resources

A campus is more than its buildings. But a campus that cares can find myriad ways to use its facilities to welcome the community. Children who borrow books from the D.C. Public Library storefront on

Wisconsin Avenue are using 5,100 square feet of space that AU owns. Bender Arena will always have a place in the memory of the high-school students who graduate there. And many organizations use the campus for their fund-raisers. At AU, even the buildings are making a difference.

2 0 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

R A I S I N G M O N E Y TO WA R D A C U R E

Last summer AU’s athletics arena, playing fields, and pool helped raise $387,000 toward a cure for juvenile diabetes. The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation held its 17th annual Real Estate Games on campus, drawing 1,200 commercial real estate professionals from 69 companies. The daylong fund-raiser, which features light-hearted three-legged races and beach-ball relays as well as hotly contested weight-lifting and swimming competitions, has now raised $2.7 million for research into the yet incurable disease affecting three million Americans.

Because everything from the facilities to refreshments and entertainment was donated,

“over 90 cents of every dollar went directly into diabetes research,” said Real Estate

Games event director Sherry Cushman.

Since beginning as a loosely organized afternoon of basketball and track raising $10,000 in 1989, the games have mushroomed. This year nearly 30 events, including volleyball, basketball, and office-chair hockey, spread throughout Bender Arena, Jacobs Fitness

Center, Reeves Aquatic Center, and Jacobs Recreational Facility. “The games really started to grow when we came to AU [in 1997], because the facility is so big and so accessible,” said Cushman. “We really couldn’t do an event like this without AU.”

And according to AU community relations officer Morris Jackson, who acted as university host for the games, that’s exactly why AU continues to be involved. “American University values involvement and partnership with the community,” he said. “We recognize the importance of being a good neighbor in the Washington, D.C., area.”

T R A I N I N G T H O S E W H O P R OT E C T U S

Last fall, 25 students graduated after completing grueling classes held at AU. But the degrees they received were not academic; rather, they were professional. These men and women weren’t college students, they were the future crop of university police in the nation’s capital.

For eight weeks they studied the ins and outs of university policing. Classes were held at AU’s Brandywine building for eight hours a day, five days a week. When the officersto-be needed to train in defensive tactics, they did so in

Bender Arena.

The academy is hosted on a rotating basis by a consortium of Washington universities. It will next return to AU in

2009. Four of the people who received their degrees at the

School of International Service lounge during the commencement ceremony now work for AU’s Office of Public

Safety. The others have moved on to jobs at Georgetown,

George Washington, Trinity, Gallaudet, Howard, Catholic, and the University of the District of Columbia.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 2 1

T E A C H I N G TO O L S

Donning green and white gowns and proud smiles, about 425 Wilson High

School graduates crossed the stage in AU’s Bender Arena to receive their diplomas on June 5. It was the second year AU hosted Wilson’s commencement exercises—and only one of the many times the schools have swapped spaces.

Classes for AU’s master of arts in teaching degree and certificate programs are held at Wilson in order to replicate the classroom setting in which the 200 to

300 students, many of whom are D.C. Public School teachers, are already working. AU’s School of Education, Teaching, and Health holds 12 classes per semester on the Wilson campus; the university equips each of the rooms it uses with the required technology and also chips in for school supplies.

AU’s partnership with Wilson is only one of the ways the university is helping local teachers sharpen their skills and expand their expertise.

2 2 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

S T R U T T I N G T H E I R S T U F F

Local animal lovers raised more than $60,000 for the Washington Animal Rescue League

(WARL) during the second annual Mutts Strut in June. That’s enough money to care for Tai, the calico kitten, Moe, the adult beagle, and 200 of their four-legged friends for six weeks—the average time animals spend at the Rescue League before they’re adopted.

Mutts Strut, which featured a 5K run and two-mile walk, drew 650 people and 200 pooches to the AU campus. The university will host the event again in 2007.

“The course was fantastic, and the weather was ideal,” said Scotlund Haisley, WARL executive director. “It was a great day for the entire family, including the canine members of the family.”

The money raised from Mutts Strut will “allow us to maintain our high standards of care until we can find loving homes for all these animals,” Haisley said. It costs about $300 to care for each animal; proceeds from the event will go toward vaccinations, food, grooming, beds, blankets, and toys for the shelter’s more than 75 animals

G O O D N E I G H B O R S

Last year, nine AU groundskeepers spent 72 hours pruning trees and planting flowers for three lucky neighborhood residents—the winning bidders in an annual silent auction to benefit Horace Mann

Elementary School.

That was only one of the many collaborations between AU and its sister school, located just across

Nebraska Avenue.

During the spring, AU groundskeepers and equipment assisted the Horace Mann PTA in spreading 30 yards of mulch underneath the playground equipment. Throughout the school year, the AU crew also performed minor maintenance projects on the Mann campus, which total about 60 service hours in 2006.

In April, AU invited 30 first and fifth graders to get their hands dirty in honor of Campus Beautification

Day. The youngsters helped plant flowers on the quad and participated in a recycling scavenger hunt organized by the AU student group Eco-Sense.

Other AU departments have relationships with the elementary school as well. Mann is one of the School of Education’s “professional development schools,” where AU students can get hands-on classroom experience. The school has also sent technology experts to train and support Mann teachers; additionally,

AU provides Internet service for the school.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 2 3

2 4 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT OF FINANCE AND TREASURER

Dear Friends,

I am pleased to report on another very successful year for American University. Financial statements summarizing the university’s operating results for the year ended April 30, 2006, are presented on the following pages. Net assets increased by $90 million to $563 million, and total assets now stand at

$844 million. The value of the university’s endowment increased by $68 million and now stands at

$340 million. Just ten years ago the endowment was only $71 million.

Restructuring the university’s capital financing was an important initiative this past year. This multifaceted process culminated with the issuance of $100 million in tax-exempt bonds to support existing debt refinancing and new capital projects, including the School of International Service and School of

Communication buildings and the Nebraska Hall renovation.

Moody’s Investors Service reaffirmed the university’s financial strength with the issuance of a highprofile report assigning the university an “A2” underlying rating. Standard & Poor’s also reaffirmed our “A” rating with a stable outlook.

The university has been working on several important capital improvement projects to enhance our facilities, ensuring an optimum environment for academic programs. To meet student housing needs, construction has begun to convert Nebraska Hall to a contemporary-style residence hall providing apartment-style housing for 115 students. Renovation is expected to be complete for the fall semester

2007. Final design to remodel the Kogod School of Business’s New Lecture Hall is in progress, with construction scheduled to start in spring 2007. This project will add instructional and office space.

The university received zoning approval to build a new School of International Service building, which is expected to be complete in fall 2009. It will provide classroom, faculty, staff, and meeting space, as well as a 300-space underground parking garage. It is being designed as a “green” building with many environmentally sensitive features. Planning is also underway for the renovation of the McKinley

Building as a future home for the School of Communication. In addition to classroom, faculty, and staff space, it will house a 200-seat theatre, a broadcast studio, and a centralized converged newsroom.

A portion of the Watkins building was renovated by converting former art studios to classrooms and administrative offices. Renovation of the remainder of the building will take place over the next year.

The university purchased a commercial office property located near the Tenley Campus, one block from the Tenleytown Metro Station. Its location and configuration make the property desirable both as an investment and as a way to meet the university’s changing office needs over time.

Reflecting upon our progress over the past year, it is evident that our ambitions are high and our momentum is strong. As we move forward, we must keep our focus on the core mission of the university and continue to involve the community to fulfill our commitment of advancing the academic and financial health of the university.

Sincerely,

Donald L. Myers

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

1800 Tysons Boulevard

McLean, VA 22102

Telephone (703) 918-3000

Independent Auditors’ Report

To Board of Trustees of American University:

In our opinion, the accompanying balance sheet and the related statements of activities and of cash flows present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of American University (the University) at April 30, 2006, and the changes in its net assets and its cash flows for the year then ended in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America. These financial statements are the responsibility of the

University’s management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audit. We conducted our audit of these statements in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America, which require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements, assessing the accounting principles used and significant estimates made by management, and evaluating the overall financial statement presentation. We believe that our audit provides a reasonable basis for our opinion.

As discussed in Note 15 to the financial statements, the University adopted Financial Accounting Standards

Board (FASB) Interpretation No. 47, Accounting for Conditional Asset Retirement Obligations, an interpretation of

FASB Statement No. 143, Accounting for Asset Retirement Obligations, in fiscal year 2006.

As discussed in Note 2, the University has restated its net assets at May 1, 2005, from amounts previously reported on by other auditors. We have audited the adjustment described in Note 2 that was applied to restate net asset balances as of May 1, 2005. In our opinion, such adjustment was appropriate and has been properly applied to the beginning net asset balance as of May 1, 2005.

July 31, 2006

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 2 5

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

(In thousands)

Assets

9

10

7

8

5

6

3

4

1

2

Cash and cash equivalents

Accounts and loans receivable, net

Contributions receivable, net

Inventories and prepaid expenses

Investments

Deposits with trustees/others

Property, plant, and equipment, net

Interest in perpetual trust

Deferred financing costs

Total assets

Liabilities and Net Assets

15

16

17

11

12

13

14

Liabilities

Accounts payable and accrued liabilities

Deferred revenue and deposits

Indebtedness

Swap agreements

Assets retirement obligations

Refundable advances from the U.S. government

Total liabilities

20

21

22

18

19

Net assets

Unrestricted

General operations

Internally designated

Capital

Designated funds functioning as endowments

Designated for plant

Total unrestricted

23

24

25

Temporarily restricted

Permanently restricted

Total net assets

26 Total liabilities and net assets

See accompanying notes to financial statements.

Balance Sheet

April 30, 2006

$ 62,067

19,521

23,458

2,011

395,589

476

323,306

14,109

3,771

$ 844,308

29,699

15,813

213,974

10,002

3,762

7,818

$ 281,068

5,380

98,083

271,410

102,345

477,218

13,603

72,419

563,240

$ 844,308

2 6 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Statement of Activities

Year Ended April 30, 2006

(In thousands)

Operating revenues and support

1

2

Tuition and fees

Less scholarship allowances

3

4

5

6

Net tuition and fees

Federal grants and contracts

Private grants and contracts

Indirect cost recovery

7

8

9

10

11

Contributions

Endowment income

Investment income

Auxiliary enterprises

Other sources

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Net assets released from restrictions

Total operating revenues and support

Operating expenses

Instruction

Research

Public service

Academic support

Student services

Institutional support

Auxiliary enterprises

Facilities operations and maintenance

Interest expense

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Total operating expenses

Excess (deficiency) of operating revenues and support over operating expenses

Transfer among funds

Nonoperating items

Investment income

Other revenue

Realized and unrealized net capital gains

Excess of nonoperating revenue over nonoperating expense

Change before cumulative effect

Cumulative effect of a change in accounting principle

Change in net assets

Net assets of beginning of year, as previously reported

Adjustment to the beginning of year net assets

Net assets of beginning of year, as restated

Net assets at end of year

General

Unrestricted net assets

Internally operations designated Capital

$ 293,160

(57,114)

236,046

613

4,727

2,703

413

5,283

48,369

1,001

—

304,528

99,679

347 10,594

8,231

—

—

—

28,051 8,398 3,882 —

27,130

49,144

25,469

28,124

8,637

274,812

29,716

(29,436)

—

—

—

—

280

—

280

5,100

—

5,100

$ 5,380

810

(2,481)

(1,671)

6,840

5,524

—

4,422

1,085

10

2,715

7,041

27,951

198

120

60

794

—

—

—

20,164

7,787

8,231

—

—

—

—

16,018

—

16,018

82,065

—

82,065

98,083

— 293,970

— (59,595)

— 234,375

—

2,708

—

—

3,526

—

—

1,196

9,017

8,732 108,609

—

485

3,881

4,851 54,789

26,678

(28,124)

(8,637)

11,748 306,724

(2,731)

21,205

—

3,000 3,000 —

53,213

56,213

74,687

(3,048)

71,639

297,322

4,794

302,116

373,755

Total

7,453

12,959

2,703

4,835

9,894

48,379

3,716

8,237

341,496

8,836

31,071

52,147

—

—

34,772

—

—

53,213

56,213

90,985

(3,048)

87,937

384,487

4,794

389,281

477,218

Temporarily Permanently restricted restricted net assets net assets

10,941

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

(8,237)

(6,632)

—

—

—

—

—

—

(6,632)

—

—

—

—

(6,632)

—

(6,632)

20,235

—

20,235

13,603

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

2,400

— 108,609

—

—

—

—

—

10,941

8,836

40,331

31,071

54,789

—

—

—

52,147

—

—

— 306,724

2,400

—

607

—

1,270

1,877

4,277

—

4,277

68,142

—

68,142

72,419

Total

293,970

(59,595)

— 234,375

—

—

—

7,453

12,959

2,703

4,835

9,894

48,379

3,716

—

337,264

30,540

—

607

3,000

54,483

58,090

88,630

(3,048)

85,582

472,864

4,794

477,658

563,240

See accompanying notes to financial statements.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 2 7

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

(In thousands)

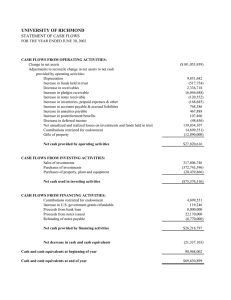

Cash flows from operating activities

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Change in net assets

Adjustments to reconcile change in net assets to net cash provided by operating activities

Cumulative effect

Net realized and unrealized capital gains

Depreciation and amortization

Bad debt expense

Changes in assets and liabilities

Decrease in accounts, contributions, and loans receivable

Increase in inventories and prepaid expenses

Increase in accounts payable and accrued liabilities

Decrease in deferred revenue and deposits

Contributions collected and revenues restricted for long-term investment

Net cash provided by operating activities

Cash flows from investing activities

12

13

14

15

16

17

Purchases of investments

Proceeds from sales and maturities of investments

Additions of property, plant, and equipment

Proceeds from deposits with trustees

Decrease in deposits with trustees/other, net

Net cash used in investing activities

Cash flows from financing activities

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Student loans issued

Student loans repaid

Payments on indebtedness

Proceeds from contributions restricted for

Investment in plant

Investment in endowment

Net cash provided by financing activities

Net increase in cash and cash equivalents

25

26

Cash and cash equivalents at beginning of year

Cash and cash equivalents at end of year

27

Supplemental disclosure of cash flow information

Cash paid during year for interest

See accompanying notes to financial statements.

2 8 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

Statement of Activities

Year Ended April 30, 2006

(2,017)

1,677

(1,450)

3,442

671

2,323

38,044

24,023

$ 62,067

$ 10,777

$ 85,582

3,048

(54,483)

13,695

546

5,151

(1,032)

973

(4,664)

(4,113)

44,703

(176,104)

180,647

(20,576)

1,106

5,945

(8,982)

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

(1)

American University

American University (the University) is an independent, coeducational university located on an 85-acre campus in northwest Washington, D.C. It was chartered by an Act of Congress in 1893 (the Act). The Act empowered the establishment and maintenance of a university for the promotion of education under the auspices of the Methodist Church. While still maintaining its Methodist connection, the University is nonsectarian in all of its policies.

American University offers a wide range of graduate and undergraduate degree programs, as well as nondegree study. There are approximately 575 total faculty members in six academic divisions and approximately

11,500 students, of which 6,300 are undergraduate students and 5,200 are graduate students. The University attracts students from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and nearly 150 foreign countries.

(2)

Summary of Significant Accounting Policies

Basis of Presentation

Net assets, revenues, gains, and losses are classified based on the existence or absence of donor-imposed restrictions. Accordingly, net assets of the University and changes therein are classified and reported as follows:

Unrestricted—Net assets that are not subject to donor-imposed stipulations.

Temporarily Restricted—Net assets subject to donor-imposed stipulations that either expire by passage of time or that can be fulfilled by actions of the University pursuant to those stipulations.

Permanently Restricted—Net assets subject to donor-imposed stipulations that they be maintained permanently by the University.

Revenues are reported as increases in unrestricted net assets unless use of the related assets is limited by donor-imposed restrictions. Contributions are reported as increases in the appropriate category of net assets.

Expenses are reported as decreases in unrestricted net assets. Gains and losses on investments are reported as increases or decreases in unrestricted net assets unless their use is restricted by explicit donor stipulations or by law. Expirations of temporary restrictions recognized on net assets (i.e., the donor-stipulated purpose has been fulfilled and/or the stipulated time period has elapsed) are reported as reclassifications from temporarily restricted net assets to unrestricted net assets. Temporary restrictions on gifts to acquire long-lived assets are considered met in the period in which the assets are acquired or placed in service.

Contributions, including unconditional promises to give, are recognized as revenues in the period received.

Conditional promises to give are not recognized until the conditions on which they depend are substantially met. Contributions of assets other than cash are recorded at their estimated fair value at the date of gift.

Contributions to be received after one year are discounted at a rate commensurate with the risk involved.

Amortization of the discount is recorded as additional contribution revenue and used in accordance with donor-imposed restrictions, if any, on the contributions. Allowance is made for uncollectible contributions based upon management’s judgment and analysis of the creditworthiness of the donors, past collection experience, and other relevant factors.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 2 9

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

The University follows a practice of classifying its unrestricted net asset class of revenues and expenses as general operations, internally designated, or capital. Items classified as general operations include those revenues and expenses included in the University’s annual operating budget. Items classified as capital include accounts and transactions related to endowment funds and plant facilities and allocation of facilities operations and maintenance, depreciation, and interest expense. All other accounts and transactions are classified as internally designated.

Transfers consist primarily of funding designations for specific purposes and for future plant acquisitions and improvements.

Nonoperating activities represent transactions relating to the University’s long-term investments and plant activities, including contributions to be invested by the University to generate a return that will support future operations, contributions to be received in the future or to be used for facilities and equipment, and investment gains or losses.

Cash Equivalents

All highly liquid cash investments with original maturities at date of purchase of three months or less are considered to be cash equivalents. Cash equivalents consist primarily of money market funds.

Deposits with Trustees/Others

Deposits with trustees consist of debt service funds and the unexpended proceeds of certain bonds payable.

These funds are invested in short-term, highly liquid securities and will be used for construction of, or payment of debt service on, certain facilities.

Investments

Equity securities with readily determinable fair values and all debt securities are recorded at fair value in the balance sheet and the fair value of these investments is based upon values provided by the external investment managers or quoted market values. In the limited cases where such values are not available, carrying value is used as an estimate of fair value. All cash and money market funds in the investment accounts are treated as investments. Real estate and other investments are recorded at historical cost or fair value at date of donation.

Endowment income included in operating revenues consists of interest and dividends from investments of endowment funds. All realized and unrealized gains and losses from investments of endowment funds are reported as nonoperating revenues. Investment income included in operating revenues consists primarily of interest and dividends from investments of working capital funds and unexpended plant funds.

The fair value of investments in limited stock partnerships is determined by using the University’s percentage of interest in each of the limited partnerships and the partnership’s estimated fair value, as disclosed in such partnership’s audited financial statements. The estimated fair value of a partnership is determined by the general partner based upon the fair value of the partnership’s investments. The investments of these limited stock partnerships, as well as certain mutual funds classified as equity securities, may include derivatives and certain private investments which do not trade on public markets and therefore may be subject to greater liquidity risk.

3 0 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

Property, Plant, and Equipment

Property, plant, and equipment are stated at cost or at estimated fair value if acquired by gift, less accumulated depreciation. Certain costs associated with the financing of plant assets are deferred and amortized over the terms of the financing. Depreciation of the University’s plant assets is computed using the straight-line method over asset’s estimated useful life, generally over 50 years for buildings, 20 years for land improvements, five years for equipment, ten years for library collections, and 50 years for art collections.

Federal Student Financial Aid Programs

Funds provided by the United States Government under the Federal Perkins Loan Program are loaned to qualified students and may be reloaned after collections. Such funds are ultimately refundable to the government.

Approximately 15% of net tuition and fees revenue for the year ended April 30, 2006, was funded by federal student financial aid programs (including loan, grant, and work-study programs).

Income Taxes

The University has been recognized by the Internal Revenue Service as exempt from federal income tax under

Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code, except for taxes on income from activities unrelated to its exempt purpose. Such activities resulted in no net taxable income in fiscal year 2006.

Fair Value of Financial Instruments

The carrying amount of cash and cash equivalents, accounts receivable, deposits with trustees, and accounts payable, and accrued expenses approximates fair value because of the short maturity of these financial instruments.

A reasonable estimate of the fair value of the loans receivable from students under government loan programs could not be made because the loans receivable are not salable and can only be assigned to the U.S. government or its designees. The fair value of loans receivable from students under University loan programs and real estate and other investments approximate carrying value.

The carrying amount of indebtedness approximates fair value because these financial instruments either bear interest at variable rates, which approximate current market rates for loans with similar maturities and credit quality, or the discount on the fixed rate indebtedness approximates a current market adjustment.

The University makes limited use of derivative financial instruments for the purpose of managing interest rate risks. Current market pricing models are used to estimate fair values of interest rate swap agreements. The fair market value of all other financial instruments in the financial statements approximates reported carrying value.

Use of Estimates

The preparation of financial statements in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles requires management to make estimates and assumptions that affect: (1) the reported amounts of assets and liabilities;

(2) disclosure of contingent assets and liabilities at the date of the financial statements; and (3) the reported amounts of revenues and expenses during the reporting period. Significant items subject to such estimates and assumptions are the value of non-traditional investments, the asset retirement obligations, and the postretirement benefit plan. Actual results could differ materially, in the near term, from the amounts reported.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 3 1

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

Restatement

The financial statements as of and for the year ended April 30, 2005, not presented herein, were audited by other independent auditors, whose report dated October 10, 2005, expressed an unqualified opinion on those statements.

During 2006, management determined that depreciation expense had been incorrectly calculated in prior years. Therefore, the net asset balances previously reported as of April 30, 2005, have been restated as of

May 1, 2005, for this adjustment. The change in net assets for the year ended April 30, 2005, as previously reported, was $70,679,000. After restatement, the change in net assets for the year ended April 30, 2005, would have been $75,473,000. After restatement, the accumulated depreciation for the year ended April 30,

2005, would have been $218,954,000.

(3)

Accounts and Loans Receivable

Accounts and loans receivable, net, at April 30, 2006, are as follows (in thousands):

5

6

7

3

4

1

2

Accounts receivable

Student

Grants, contracts, and other

Accrued interest

Student loans

Less allowance for uncollectible accounts and loans

$ 3,949

6,724

412

9,002

20,087

(566)

$ 19,521

(4)

Contributions Receivable

Contributions receivable, net, are summarized as follows at April 30, 2006 (in thousands):

12

13

14

10

11

8

9

Unconditional promises expected to be collected in

Less than one year

One year to five years

Over five years

Less unamortized discount

Less allowance for doubtful accounts

$ 13,638

12,014

369

26,021

(737)

(1,826)

$ 23,458

Contributions receivable were discounted at rates ranging from 3% to 6.5%, which approximates the risk free rate of return for the expected term of the promises to give. As of April 30, 2006, the University had also received bequest intentions of approximately $10.0 million. These intentions to give are not recognized as assets and, if the bequests are received, they will generally be restricted for specific purposes stipulated by the donors, primarily endowments for faculty support, scholarships, or general operating support of a particular department of the University.

3 2 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

(5)

Investments

Investments by type at April 30, 2006, are as follows (in thousands):

7

8

5

6

9

3

4

1

2

Money market funds

U.S. government obligations

Fixed income mutual funds

Corporate stocks

Equity mutual funds

International equity mutual funds

Real estate mutual funds

Real estate and other

$ 5,256

820

114,552

122,925

29,214

97,863

17,249

7,710

$ 395,589

Investments in debt securities and equity securities consist primarily of investments in mutual funds managed by external investment managers.

At April 30, 2006, the assets of endowments and funds functioning as endowments were approximately

$340 million.

(6) Property, Plant, and Equipment

Property, plant, and equipment and related accumulated depreciation and amortization at April 30, 2006, is as follows (in thousands):

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Land and improvements

Buildings

Equipment

Construction in progress

Library and art collections

Accumulated depreciation and amortization

$ 39,141

379,546

77,185

9,759

54,530

560,161

(236,855)

$ 323,306

Construction in progress at April 30, 2006, relates to building improvements and renovations.

For the year ended April 30, 2006, depreciation expense was approximately $13.3 million.

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y 3 3

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

(7)

Indebtedness

The University classifies its debt into two categories: core debt and special purpose debt. Core debt represents debt that will be repaid from the general operations of the University and includes borrowings for educational and auxiliary purposes. Special purpose debt represents debt that is repaid from sources outside of general operations and includes borrowings for buildings, which house some administrative offices, along with rental space.

Indebtedness at April 30, 2006, consists of the following (in thousands):

7

8

9

1

2

3

4

5

6

Core Debt

District of Columbia variable rate weekly demand revenue bonds, The American University Issue Series 1985, maturing in 2015

District of Columbia variable rate weekly demand revenue bonds, The American University Issue Series A, maturing in 2015

District of Columbia University Revenue Bonds, American University

Issue Series 1996, maturing in 2026 net of discount of $1,136 in 2006

District of Columbia University Revenue Bonds, American University

Issue Series 1999, maturing in 2028

District of Columbia University Revenue Bonds, American University

Issue Series 2003, maturing 2033

Total core debt

10

Special Purpose Debt

Note payable, variable rate, due in full in 2021

Note payable, variable rate, due in full in 2020

Total special purpose debt

Total indebtedness

$ 48,900

12,000

58,074

21,000

37,000

176,974

22,000

15,000

37,000

$ 213,974

The principal balance of bonds and notes payable outstanding as of April 30, 2006 are payable as follows:

11

12

13

14

15

16

Year ending April 30:

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Thereafter

$ 1,475

1,555

1,640

16,735

23,840

168,729

$ 213,974

3 4 A U I N T H E C O M M U N I T Y

A M E R I C A N U N I V E R S I T Y

Notes to Financial Statements

April 30, 2006

District of Columbia Bonds Payable