2010–2011 ANNUAL REPORT

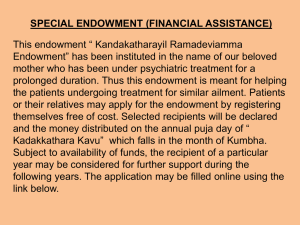

advertisement