Population and Reproductive Health Oral History Project Cory L. Richards

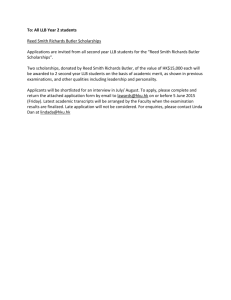

advertisement