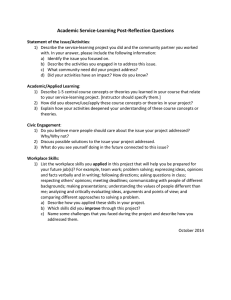

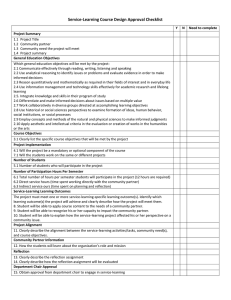

F G S - L

advertisement