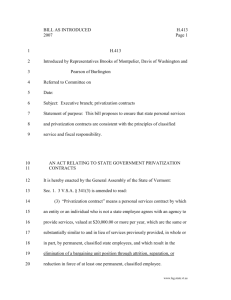

W P N 3

advertisement