safety signals status &

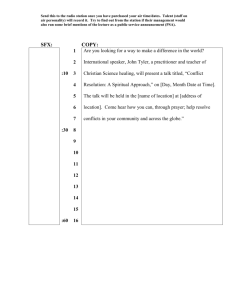

advertisement