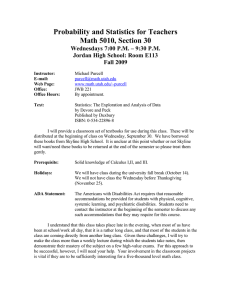

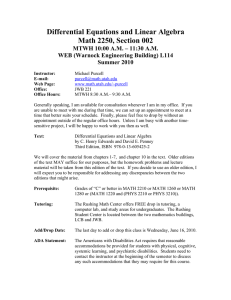

The Fairy-Queen H. NEVILLE DAVIES (UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM)

advertisement

‘To Sing and Revel in these Woods’: Purcell’s The Fairy-Queen and The Honourable Entertainment at Elvetham H. NEVILLE DAVIES (UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM) It seems to have escaped the notice of Purcell scholars that one of Henry Purcell’s most memorably comic creations—the attempted seduction of Mopsa by Coridon in The Fairy-Queen—has a text derived from an Elizabethan poem by Nicholas Breton. Perhaps the reason for this curious oversight is because the words that Purcell set so inventively are in lively dialogue form, and thereby disguise their origin, effectively concealing even their generic as well as their particular derivation: Enter Coridon, and Mopsa. Co. Now the Maids and the Men are making of Hay, We have left the dull Fools, and are stol’n away. Then Mopsa no more Be Coy as before, But let us merrily, merrily Play, And Kiss, and Kiss, the sweet time away. Mo. Why how now, Sir Clown, how came you so bold? I’d have you to know I’m not made of that mold. I tell you again, Maids must Kiss no Men. No, no; no, no; no Kissing at all; I’le not Kiss, till I Kiss you for good and all. Co. No, no. Mo. No, no. Co. Not Kiss you at all. Mo. Not Kiss, till you Kiss me for good and all. Not Kiss, &c. Co. Should you give me a score ’Twould not lessen the store, Then bid me chearfully, chearfully Kiss, And take, and take, my fill of your Bliss. Mo. I’le not trust you so far, I know you too well; Should I give you an Inch, you’d take a whole Ell. Then Lordlike you Rule And laugh at the Fool. No, no, &c.1 1 The Fairy-Queen: An Opera, edited by Roger Savage, in Michael Burden (ed.), Henry Purcell’s Operas: The Complete Texts (Oxford, 2000), p. 380. This text, reprinted from the quarto of 1693, probably represents a printed version of the Coridon and Mopsa dialogue as it was when it was received by Purcell. But Purcell himself then made minor alterations and added a few lines at the end. For these, see Yet although the source poem presents a similar situation, the mode adopted by Breton had been narrative and voyeuristic rather than quasidramatic: In the merrie moneth of May, In a morne, by breake of day, Forth I walked by the wood side, Where as May was in his pride. There I spied, all alone, Phyllida and Corydon. Much adoe there was, God wot, He would love, and she would not. She said, never man was true: He said, none was false to you. He said, he had loved her long: She said, love should have no wrong. Coridon would kisse her then: She said, maides must kisse no men, Till they did for good and all. Then she made the shepherd call All the heavens to witnesse truth, Never lov’d a truer youth. Thus with many a pretie oath, Yea and nay, and faith and troth, Such as silly shepheardes use, When they will not love abuse; Love, which had beene long deluded, Was with kisses sweet concluded: And Phyllida, with garlands gay, Was made the Lady of the May.2 Modes, then, differ, as indeed does the amorous outcome, for Breton’s demurely reluctant Phyllida finally relents when sufficiently reassured, while Purcell’s altogether feistier Mopsa persists in rejecting her suitor’s persuasions to love. But in both cases the would-be lover is a shepherd or rustic (‘Clown’) named Coridon, and despite the development of a conventionally yielding Phyllida into a hard-nosed Mopsa, the close kinship of the two girls is clearly demonstrated by the words ‘Maids must Kiss no Men’3 and ‘for good and all’ uttered by both ‘The Song Texts with Music by Purcell’, edited by Timothy Morris, in Complete Texts, pp. 504-505. Fairy-Queen line numbers refer to Savage’s edition. 2 Jean Wilson (ed.), Entertainments for Elizabeth I (Woodbridge, 1980), pp. 113-14. 3 Although the Fairy-Queen playbook retains these words precisely as they were in the poem, Purcell doubled the negative:‘Maids must never kiss no men’ (Complete Texts, p. 504). of them, and uttered in identical circumstances. Moreover, since Coridon’s name survives in The Fairy-Queen only as a fossilized relic of the source text—for in the new context the name is retained merely for use as a speech prefix or within stage and printer’s directions—there is every reason to suspect that it derives from a precursor where its use was fully functional. Other less striking similarities that lend support to the notion that the dialogue is directly indebted to the poem include the link between ‘the merrie moneth of May’ and ‘merrily, merrily Play’, where rhyme combines significantly with the shared adjective or adverb, as well as the link between Phyllida’s ‘never man was true’ and the combative application of this comprehensive aphorism in the direct personal rebuff given by Mopsa’s bluntly forthright ‘I’le not trust you so far, I know you too well’. Perhaps, too, the Purcellian Coridon’s fond hope of kissing ‘the sweet time away’ owes something to the ‘kisses sweet’ with which his namesake and Phyllida had happily concluded their more productive May-time encounter. But above all, anyone who remembers Purcell’s hilariously extended treatment of Mopsa’s coyly defensive ‘No, no, no no, no, no kissing at all’, which eventually compels even her increasingly frustrated lover to follow suit and sing an absurdly interrogative ‘Why no, no, no, no, no kissing at all?’, will realise how resourcefully the composer has responded to and expanded Breton’s ‘Much adoe there was, God wot’.4 Of course, the credit for this delicious comedy, with Mopsa repeatedly edging away when Coridon with growing desperation repeatedly urges her to relent, is largely Purcell’s, but the necessary launch pad was provided by Breton, and due ackowledgement must also be given to the Fairy-Queen librettist who had the seminal idea of turning the sweetly erotic pastoralism of Breton’s narrative into sharply confrontational dialogue, and who introduced the cruder vigour of anapaests that pointed Purcell in the direction of music dancing in and out of the bucolic rhythms of compound time. That Breton’s charming little piece provided a literary basis for Purcell’s boldly confident development of it need come as no surprise. It was, after all, a standard text for composers, and its general currency had been ensured when it was anthologised in England’s Helicon (1600). Purcell, we may reasonably suppose, probably knew three of the four surviving settings. By far the most familiar of them throughout the second half of the century must have been John Wilson’s pleasantly tuneful strophic setting, widely disseminated in manuscript and printed sources as a solo song and as a part-song for three voices.5 But there was also a later, Purcell’s setting also extends the dialogue by the addition of a few lines at the end. See Complete Texts, p. 505. 5 See especially Ian Spink (ed.), English Songs, 1625-1660, Musica Britannica, 33 (London, 1971), pp. 54 and 196-97. Early printed sources include John Wilson, 4 somewhat ponderous four-part strophic setting by Benjamin Rogers in which an unfortunate combination of heavy cadential punctuation and oleaginous suspensions and passing-notes persistently lubricating the weak beats gives the music an inappropriately hymn-like character.6 Neither Wilson nor Rogers, however, was concerned to respond to their chosen text with musical wit or expressive particularity, though Wilson’s unpretentious setting at least permits the verse to retain its easy grace and to maintain a proper narrative impetus. Yet from the beginning of the century, and more ambitious in scale, came a pair of three-part Italianate madrigals by Michael East: ‘In the Merry Month of May’ setting lines 112, and ‘Corydon Would Kiss her Then’, its sequel, setting lines 13-26.7 Unlike the later strophic settings, East’s music seizes every opportunity to give apt musical expression to verbal detail, and the reported exchanges between Corydon and Phillida are well handled in a manner that suggests the reciprocations of actual dialogue. The division of the text, though, to provide verse for two independent madrigals, with emphatic musical closure to the first of them, impedes the narrative by disrupting the overall trajectory of the amorous interaction, and larger meaning is sometimes sacrificed to local effect, as when the words ‘all alone, / Phillida and Corydon’ are set in a way that suggests misleadingly, before Corydon receives any mention, that a solitary Phillida is observed entirely on her own. Yet even though East’s prime endeavour was simply to write musically effective madrigals, and the poem is made to serve, sometimes atomistically, this distinctive purpose, his madrigalian treatment may nevertheless have contributed to the evolution of the Fairy-Queen dialogue. For instance, his word repetition in ‘merry, merry, merry month of May’ could have helped to turn Breton’s succinctly expressed ‘In the merrie moneth of May’ into the Fairy-Queen’s ‘Let us merrily, merrily Play’, while East’s setting of the words ‘for good and all’ may be faintly echoed by Purcell’s setting of the same phrase. East may also have supplied the name Mopsa, for the twelfth item in East’s Madrigales to 3. 4. and 5. Parts (1604), the volume which has as its first two items the paired Breton madrigals, is a madrigal addressed to the jilted ‘Mopsie’. The original music for Breton’s poem—a polyphonic setting for three voices quite probably unknown to Purcell—was by John Baldwin.8 Cheerful Ayres (1660), John Playford (ed.), Select Musicall Ayres and Dialogues (1653), Playford (ed.), Select Ayres and Dialogues (1659), Playford (ed.), The Musical Companion (1667 and 1673), Playford (ed.), The Treasury of Music (1669). 6 John Playford (ed.), The Musical Companion (London, 1673), pp. 208-209. 7 The English Madrigalists, ed. Edmund H. Fellowes, rev. Thurston Dart, vol. 29 (London, 1960), pp. 6-14. 8 Ernest Brennecke, ‘The Entertainment at Elvetham, 1591’, in John H. Long (ed.), Music in English Renaissance Drama (Lexington, 1968), pp. 48-51. The only features of the composition that in any way prefigure Purcell’s Fairy-Queen dialogue are repetition of the word ‘merry’ which, because the three voices enter separately, is sung successively by each voice in turn, and a nicely contrived ‘no, no, no’ effect in the setting of ‘maids must kiss no men’, when the top voice sings the word half a beat after the bass voice, the middle voice then sings it one beat after the top voice, and on the following beat all three voices come together for ‘men’. But whether or not Purcell recalled Baldwin’s music (not printed until 1968) or any of the subsequent music setting Breton’s words, it is evident that the anonymous compiler (or compilers) of the Fairy-Queen playbook were thoroughly familiar with the unique occasion for which the poem had been written and Baldwin’s music composed. They come from the sequence of entertainments presented over a four-day period to honour Elizabeth I during the queen’s visit to Elvetham in Hampshire in 1591. The printed account, of which there were three early editions, prints the text of the poem, giving it the title ‘The Plowmans Song’ in two of those editions and ‘The Three Men’s Song, sung the third morning under hir Majesties Gallerie window’ in the other. The account explains that About nine of the clock, as her Majesty opened a casement of her Gallerie window, there were three excellent Musicians, who, being disguised in auncient countrey attire, did greet her with a pleasant song of Coridon and Phyllida, made in three parts of purpose. The song, as well for the worth of the dittie, as for the aptnes of the note thereto applied, it pleased her Highnesse, after it had been once sung, to commaund it againe, and highly to grace it with her chearefull acceptance and commendation.9 Inevitably, one remembers A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Bottom’s enthusiastic notion of playing the part of the Pyramus and Thisbe lion with such aplomb that the Duke would be sure to call out ‘Let him roar again, let him roar again’ (I.2.64-65), but the Corydon and Phillida performance was not the only royal encore at Elvetham. Elizabeth was to be even more delighted the following morning by the homage paid to her by the Fairy Queen and the Fairy Queen’s attendant troupe of singing and dancing fairies: Her Majestie was no sooner readie, and at her Gallerie window looking into the Garden, but there began three Cornets to play certaine fantasticke 9 Entertainments for Elizabeth I, p. 113. All quotations are from this edition. dances, at the measure whereof the Fayery Quene came into the garden, dauncing with her maides about her. Shee brought with her a garland …[and] spake as followeth…to her Majestie. I that abide in places under-ground, Aureola, the Quene of Fairy land, That every night in rings of painted flowers Turne round, and carrell out Elisaes name: Hearing that Nereus and the Sylvane gods Have lately welcomde your Imperiall Grace, Oapend the earth with this enchanting wand, To doe my duety to your Majestie, And humbly to salute you with this chaplet, Given me by Auberon, the Fairy King. Bright shining Phoebe, that in humaine shape, Hid’st Heaven’s perfection, vouchsafe t’accept it: And I Aureola, belov’d in heaven, (For amorous starres fall nightly in my lap) Will cause that Heavens enlarge thy goulden dayes, And cut them short, that envy at thy praise. After this speech, the Fairy Quene and her maides daunced about the Garden, singing a Song of Sixe parts, with the musicke of an exquisite consort; wherein was the lute, bandora, base-violl, citterne, treble-violl, and flute. (p. 115) The account then prints the words of the fairies’ song, and notes that ‘This spectacle and musicke so delighted Her Majesty, that shee commaunded to heare it sung and danced three times over’, rewarding the performers with thanks and ‘gracious larges’ (p. 116). In Purcell’s opera, almost exactly a century later, it is the Fairy Queen herself, there identified as Shakespeare’s Titania rather than as Elvetham’s Aureola, who is the provider or recipient of all the inset musical entertainments. In Act I the ‘Fairy Coire’ is employed to ‘Sing, and entertain’ her Indian boy (lines 154-55), while in Act III their commision is to provide ‘a Fairy Mask’ for her lover’s entertainment (lines 895-96), a masque that among other delights offers Bottom the Coridon and Mopsa dialogue. Meanwhile, in Act II, the fairies—‘Some shall Dance, and some shall Sing’ (line 462)—are required to perform for their queen’s own gratification, and then to sing her asleep. Rather differently, the performers of the Masque of the Four Seasons that salutes the rising sun with ‘all variety of Musick’ (line 1245) in Act IV are not explicitly identified as fairies, but must be so since the performance is commissioned by Titania at Oberon’s instigation, and celebrates not only the banishment of night and its fierce vexations but also the birthday of the fairy king. In Act V ‘a short simphony’ of strange ‘Fairy Musick’ (lines 1486-89) prepares the Duke for the musical intervention of pronubial Juno, and the final entertainment that then ensues at Oberon’s command, and in which singing and dancing fairies masquerade in a fantastic variety of non-fairy roles, is performed ostensibly ‘to entertain our [Fairy] Queen’ (line 1539). But the important point is that both the Elvetham entertainment and the entertainments for which Purcell provided music in The Fairy-Queen employ singing and dancing fairies, and that, since Queen Elizabeth was not only entertained by the Fairy Queen but was herself envisaged as the Fairy Queen, most notably by Spenser, the argument that there is a significant link between the Elizabethan text and Purcell’s opera is further strengthened. More particularly, though, Aureola’s hailing of Elizabeth as ‘Bright shining Phoebe… in humaine shape’, together with the presentation of Elizabeth in the next oration as the sun (i.e. as a feminized Phoebus Apollo) whose ‘glorious beames’ make summer possible, whose arrival is springtime, and whose absence marks autumn and winter, provides the basis of The Fairy-Queen’s Act IV masque. There ‘Phœbus appears in a Chariot drawn by four Horses, and Sings’ (lines 1273-74), his self-defining song allowing him to assert: ‘I dart forth my Beams, to give all things a Birth’ (line 1277), and after a chorus of acclamation, each of the four seasons sings an appropriately characteristic musical tribute. The speaker of the oration that represents Elizabeth as the lifegiving sun is a poet dressed in black and with the laurel of his garland emblematically ‘mixed with ugh branches, to signifie sorrow’ (p. 116). He presents himself thus because his oration, recurrently punctuated by the refrain ‘For how can Sommer stay when Sunne departs?’, addresses Elizabeth as she leaves Elvetham at the end of her visit. The poetic imagery associated with lamenting her departure has therefore been translated into the symbolic figures greeting the arrival of Phoebus in the opera, though the placing of the oration near the end of the Elvetham sequence is mirrored by the placing of the Masque of the Four Seasons just before the end of Act IV of The Fairy-Queen.10 A similar mirroring of position accompanied by reversal of treatment is found when the role of the poet welcoming Elizabeth at the very beginning of her Elvetham visit is compared with the role of the blindfolded poet in Act I of The Fairy-Queen. As Bruce Wood and Andrew Pinnock have demonstrated, Does the lament for Elizabeth’s departure help to account for Oberon’s request in The Fairy-Queen to hear the Plaint of Laura (line 1529-37)? 10 the episode in which a blindfolded poet is tormented by fairies who make him confess that he is both drunk and the author of bad verse was adapted from Suckling’s play The Goblins.11 Purcell’s poet is clearly based on Suckling’s, even if we also recall episodes in Lyly, Shakespeare and Jonson that relate to his bewildering and bruising experience at the hands of the fairies; but it was the Elvetham entertainment that had introduced the basic strategy of using the figure of a poet to effect a transition into the dream-world of fairy enchantment. Elizabeth, however, had been welcomed into the delightful and ordered hospitality of the Earl of Hertford’s park at Elvetham, not benighted in a disorienting forest of confusions and torment presided over by a jealous Oberon, a proud Titania, and a mischievous Puck. Consequently, the two poets are diametrically different. In contrast to the eloquence of the Elvetham poet who had greeted the royal guest in properly learned fashion ‘with a Latine Oration, in heroicall verse’ (p. 102), the Sucklingesque poet of The FairyQueen is an incoherent stammerer (see Purcell’s ‘Fi-fi-fi-fill up the bowl…Tu-tu-turn me round…’) quite unaware that he has come into the royal presence. Replacing Elvetham’s veridicus vates (p. 102), then, is The Fairy-Queen’s self-confessed ‘scurvy Poet’ (line 188), and instead of holding ‘an olive branch in his hand’ (p. 102) he clutches a drinking bowl. Instead of ‘Apollo [being] patrone of his studies’ he plays drunkenly at blindman’s buff (line 175). This means that despite his unconvincing claim that he hopes one day ‘to wear the Bays’ (line 196), it is an incapacitating blindfold rather than Apollo’s laurel garland that he has on his head (p. 102). And while the Elvetham poet is honourably esteemed as ‘vates cothurnatus, and not a loose or lowe creeping prophet, as poets are interpreted by some idle or envious ignorants’ (p. 102), his low-creeping Fairy-Queen counterpart is forced to confess how pathetically poor he is (line 193). The park at Elvetham to which the poet welcomed Queen Elizabeth had been amazingly transformed for her visit. Most remarkable of all was the creation of a great artificial lake that Jean Wilson judges to have been a hundred yards across at its widest point (p. 96), and that boasted three curiously shaped islands. One took the form of a three-masted ship, a hundred foot in length and with three trees and their branches representing the masts and rigging, another was shaped like ‘a Fort twenty foot square every way, and overgrown with willows’ (p. 100), while the third was ‘a Snayl Mount, rising to foure circles of greene privie hedges, the whole in height twentie foot, and fortie foote broad at the bottom’. It was on and around this lake that the most ambitious of the 11 ‘The Fairy Queen: A Fresh Look at the Issues’, Early Music, 21 (1993), 44-62. entertainments, those of the second day, were set, and it was this water pageantry that was to have the greatest impact on the staging of The Fairy-Queen. For in Act III, when Titania wishes to entertain Bottom with ‘a Fairy Mask’, she charges her elves to ‘change this place / To my Enchanted Lake’ (lines 894-96), and the ensuing transformation produces not only a water scene, but also trees pressed into service to represent architectural features, and ‘Two great Dragons’ whose bodies form the arches of a spectacular bridge ‘through which two Swans are seen in the River at a great distance’ (lines 901-904). At Elvetham the fanciful use of trees and shrubbery was an obvious way of exploiting the natural resources of the park and of working within its limitations, whereas on the Dorset Garden stage the scene painters for The Fairy-Queen were not constrained in this manner. They were at liberty to give their imagination free rein and depict whatever they wished. Yet even so, the constraints of Elvetham linger in their work when they choose to depict trees deployed in the Elvetham way. Similarly, the scenic concept of a dragon bridge also recalls Elvetham, since the Elvetham conceit of the ‘Snaile Mount’ or island was, like that of the bridge, of a physical structure supposedly created by the body of a fearsome monster, and was likewise associated with an expanse of water set in an artfully contrived landscape. ‘The Snayl Mount nowe resembleth a monster, having hornes full of wild-fire, continually burning’, explains the Elizabethan account, and Nereus addressing the Queen elaborates this idea by incorporating an adulatory allusion to the events of 1588 (complete with a Bottom-like assurance that there’s no need to be alarmed): Yon ugly monster creeping from the South To spoyle these blessed fields of Albion, By selfe same beams is chang’d into a snaile, Whose bullrush hornes are not of force to hurt. As this snaile is, so be thine enemies! (pp. 109-110) But while the Elvetham conceit was grounded in the peculiarities and special circumstances of the location, with the monster being conceived as both mythical and allusive, the Fairy-Queen dragon bridge that it inspired is envisaged merely as luxurious spectacle. The scene painters are adapting their source purely to create a marvellous visual effect, not resourcefully seeking significance in landscape or contriving to pay an ingenious compliment to a reigning monarch. Similarly too, the swans that ‘come Swimming on through the Arches to the bank…as if they would Land’ and that then ‘turn themselves into Fairies, and Dance’ before Bottom and Titania (lines 921-24) are derived from more elaborately programmatic antecedents at Elvetham, where floating on the lake was a ‘pinnace’ in which, rather than fairies, was the sea nymph Neaera on her way to present a ‘sea-jewell’ to the Queen. Accompanying Neaera were her musicians, ‘three Virgins, which, with their cornets, played Scottish gigs, made three parts in one’ (p. 108). But in addition there was vocal music on the water too: ‘three excellent voices , to sing to one lute, and in two other boats hard by, other lutes and voices, to answer by manner of eccho’ (p. 108). The text of the song, with ‘everie fourth verse [i.e. line] answered with two Echoes’, is included in the published account (pp. 110-111) and may well have provided a generic model for the echo song in Act I of The Fairy-Queen, ‘Come all ye Songsters of the Sky’ (lines 470-90), since it too employs the device of a double echo, and is followed first by ‘a Composition of Instrumental Musick, in imitation of an Eccho’ and then by ‘a Fairy Dance’ (lines 490-92). The Fairy-Queen swans who ‘turn themselves into Fairies’ when they reach land, and there dance, are then frightened away by ‘Four Savages’ who suddenly appear and ‘Dance an Entry’ (lines 923-28). In the list of dramatis personae these disruptive intruders are identified as ‘Woodmen’ (line 21), and in Purcell’s manuscript score, where the upward rushing octave scales of their music graphically depict the way they chase off the panic-stricken fairies, they are referred to as ‘green men’. They too come from the water pageant at Elvetham. For at the conclusion of the Elvetham echo song, five Tritons from the lake having sounded their trumpets, came Sylvanus with his attendants, from the wood: himself attired, from the middle downewards to the knee, in kiddes skinnes with the haire on; his legges, bodie, and face, naked, but died over with saffron, and his head hooded with a goates skin, and two little hornes over his forehead…His followers were all covered with ivy-leaves, and bare in their hands bowes made like darts. (p. 111) When Sylvanus had paid his respects to the Queen, there followed some boisterous rough and tumble with a water fight breaking out between the sylvans and the sea-gods, after which, Sylvanus, being so ugly, and running toward the bower at the end of the Pound [i.e. lake], affrighted a number of the country people, that they ran from him for feare, and thereby moved great laughter. (p. 112) In The Fairy-Queen the dance of the ‘savages’ and the panic that they create among the dancing fairies is followed by the Coridon and Mopsa dialogue already discussed. But it can now be shown how the rejection of Coridon’s amorous advances, which brings the dialogue to a conclusion that differs from that of Breton’s Coridon and Phillida poem, also has an origin in the Elvetham entertainment. For Sylvanus is presented as being hopelessly in love with the sea nymph Neaera who has long rebuffed him, and the slapstick of the water fight is presented as a farcical episode in his ill-fated wooing of the unattainable nymph he so dotes on. In The FairyQueen, Sylvanus’s ridiculous failure as a suitor at Elvetham was to become, in yet another transformation, Corydon’s comic failure to seduce Mopsa. Once the extent of the debt that The Fairy-Queen owes to The Honourable Entertainment at Elvetham is appreciated, it becomes plain that to regard the work simply as an operatic abridgement or adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is dangerously misleading. We need to think instead in terms of a conflation of a pair of late Elizabethan texts: A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Honourable Entertainment. And from this follows several conclusions. For instance, it becomes evident that the association sometimes made by modern scholars between these two texts of the 1590s, and that has been a regular part of editorial commentary on A Midsummer Night’s Dream since the time of Rowe, has a history that penetrates right back into the seventeenth century. 12 In recent years, Shakespearians have tended to be dismissive of the supposed link, but the knowledge that seventeenth-century readers were disposed to see a connexion suggests that it is possible that insufficient attention is being paid nowadays to the full range of interest to be found in the relationship. It becomes clear, too, that the Preface to the 16921693 Fairy-Queen playbooks that focuses so insistently on France and Italy should not be interpreted as evidence that the preparation of the text of The Fairy-Queen, either as a whole or even as far as its nonShakespearian operatic additions are concerned, was undertaken with continental example principally in mind. In fact, this is a thoroughly English opera, intended, as the Preface stoutly maintains, to be no less esteemed than those of Europe, but not therefore aping European example. The principal conclusion, however, must be that the old complaint that The Fairy-Queen is a gallimaufrey, deplorably less unified than A Midsummer Night’s Dream—a complaint that continues to be voiced despite the sensitive and intelligent defence offered by Roger Savage13—needs to be set alongside the antithetical observation that The Fairy-Queen is more dramatically unified than its other progenitor, those diverse entertainments at Elvetham. Awareness that the genre to which this work belongs is neither that of the straight play on the one hand nor that of disparate entertainments such as those Queen Elizabeth 12 Particularly influential has been E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 vols (Oxford, 1923), I, 124. 13 Notably in ‘The Shakespeare-Purcell Fairy Queen: A Defence and Recommendation’, Early Music, I (1973), 200-221, and ‘The Theatre Music’ in The Purcell Companion, ed. Michael Burden (London, 1995), especially pp. 364-78. encountered in Hampshire on the other hand is crucial to an understanding of its remarkable blend of unity and diversity. In their strikingly different ways both Shakespeare’s masterpiece of a play and the Earl of Hertford’s enterprising though comparatively undistinguished entertainment deliberately assemble an extraordinary range of elements, but, as befits a play, in the case of A Midsummer Night’s Dream it is the imaginative resolution of those elements into concordant unity that is the playwright’s supreme achievement, whereas in the case of the Elvetham entertainments, as befits the nature of its special occasion, it is the delightful and inventive diversity that matters most. Yet, for all that, coherence of a kind was not lacking at Elvetham. For unity is to be found not in the constituent entertainments, but rather in the embracing entity of the park itself, with all its resources, natural and contrived, human and supernatural, collaboratively engaged in a concerted festive endeavour, and in the powerful focal presence of the sovereign visitor. The FairyQueen, then, shares and reconciles some of the characteristics of both its progenitors, and these include a commitment to presenting a series of wonderfully diverse entertainments whose progressively expanding exubriance excitingly threatens to overwhelm the sort of coherence expected in a conventional play. Yet that notion of coherence is exhilaratingly challenged, not destroyed, for the central eponymous figure of the Fairy Queen herself, the supportive framework supplied by Shakespeare’s abbreviated play, and the cohesive power of Purcell’s music bind together the work as a convincing whole. Like the disparate entertainments at Elvetham, the entertainments in The Fairy-Queen are indispensible, though in their individual quality and in their imaginative integration they rise to a level that The Honourable Entertainment at Elvetham could scarcely begin to approach.