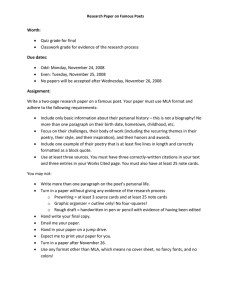

The Culture of Slander in Early Modern England

advertisement

M. Lindsay Kaplan, The Culture of Slander in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), xii + 148 pp., ISBN 0521584086 The scope of this short, cogently argued book is more limited that its title might suggest. Rather than exploring the significance of slander in the culture of early modern England, and the flood of litigation it triggered, Lindsay Kaplan argues that ‘slander provides a model crucial for the analysis of power relations between poets and state’ (p. 1). A rather combative Introduction sets out the limitations of ‘censorship’ as the paradigm governing these relations, and proposes slander as a more rewarding means of understanding them. Chapter 1 analyses the legal framework, noting that ‘slander’ was defined in terms of its effects rather than its truth or falsity, and surveys royal fears of the slanderous nature of contemporary satire, which led to the Bishop’s Ban of 1599. The book’s central thesis is that poets found a way to circumvent this ban. Reversing the claim that they slandered the state, they presented poets and princes as allies in the task of exposing and punishing vice. It was not the poet who was guilty of slander, but those denouncing him as libellous and seditious. Kaplan pursues this thesis by examining three texts, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, Jonson’s Poetaster and Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Jonson’s play, she observes, lashes out at the vices and folly of poetasters while defending the true poet as a moral judge, called to expose the faults of both subjects and lesser magistrates. This defence of the poet’s public calling was undermined, however, by Jonson’s failure to sustain a clear distinction between attacking vices and individuals. His ‘Apologetical Dialogue’ insisted that he had named no names, yet this play triggered complaints from those who felt targeted, and his response made it plain that the play was in part an act of vengeance against those he saw as his persecutors. The Poetaster was as much feud as moral satire. Finding the moral centre of Measure for Measure presents a far greater challenge. Kaplan centres her analysis on the behaviour of Lucio and the Duke, and the relationship between them. The Duke, she notes, punishes Lucio ostensibly for fornication but really for slandering him; and yet the Duke himself, both in his own persona and in disguise as Friar Lodowick, slanders most of the other characters, and indeed most of the population of Vienna, in the course of machinations designed to bolster his authority rather than eradicate vice. His own record in government is dubious, as he acknowledges, and his choice of Angelo equally so, intended partly to see whether power corrupts, partly to divert public hostility should Angelo remain true to his charge and impose a regime of moral repression. The ‘message’ of the pay has remained elusive. While the Duke triumphs, it is less clear that he has won or deserved respect. For Kaplan the message is that slander was a two-edged weapon; Lucio is punished by the victor, but the play calls into question the state’s own use of public slander and humiliation, and thus its own moral authority. For Jonson, the poet is the ally of the good ruler; for Shakespeare, a potentially rival arbiter. In a brief conclusion, Kaplan links these texts to the work of historians such as Pauline Croft and Alastair Bellamy, who have explored the proliferation of political libels under the early Stuarts, and their effect in helping to politicize the nation and undermine the authority of the Stuart regime. Scholars would be unwise to dismiss the importance of censorship, broadly conceived, in shaping what poets and playwrights wrote. Whatever the limitations and inner divisions of the Renaissance state, writers were well aware of limits to what was permissable, and generally sought to operate within them. Kaplan’s book, which begins by arguing that the concept of censorship serves to ‘distort our understanding” (p. 1), ends more emolliently by offering censorship and slander as complementary tools of analysis. On that basis, this thoughtful and thought-provoking book deserves a warm welcome. Bernard Capp University of Warwick