People Pressures on Previously Pristine Places: A Comparative Study of Coral Biodiversity Near Hoga Island, Indonesia Chelsea R Vaughn and L David Smith Chelsea R. Vaughn and L. David Smith

advertisement

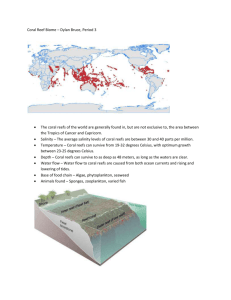

People Pressures on Previously Pristine Places: A Comparative Study of Coral Biodiversity Near Hoga Island, Indonesia Chelsea R Vaughn and L David Smith Chelsea R. Vaughn and L. David Smith Department of Biological Sciences , Smith College, Northampton, MA INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION Coral reefs are one of the world’s most valuable ecosystems. They provide important habitat for more than a quarter of all marine species, are one of the most productive areas on Earth, prevent erosion of coastal areas, and provide living resources (fish) and services (tourism) for humans. An area of particular interest is Southeast Asia, which is home to the most species rich reef systems on Earth (Bryant et al 1998) home to the most species‐rich reef systems on Earth (Bryant et al., 1998). Survey results show that the high impact site, Sampela, had significantly lower percent cover of living organisms (hard coral, soft coral, sponges, and algae) than the low impact site, Pak Kasims. In terms of genus diversity, Sampela also had fewer genera overall and more genera with few individuals. Together, these data indicate that Pak Kasims is a healthier reef healthier reef. In order to measure the reef communities at the two sites, each site was subdivided into three zones: the reef flat, crest, and slope. The flat and slope were each measured 5 meters from the crest. Within each zone, a 50‐meter line transect was placed running parallel to the reef crest with point sampling done every 50 centimeters. Four transects were completed for each reef zone; a total of twelve transects per reef. Data analysis was completed by using 2‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models to compare composite groupings of benthic categories by both reef and zone. As the value of marine biodiversity hotspots is realized, the push for preservation is increased. One method of conservation is through the implementation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). MPAs are typically zoned into areas that differ in the amount of human interaction they receive (e.g., research‐only areas, no‐fishing zones, tourism‐ only, etc). However, even in MPAs, proximity to anthropogenic influence can create disparity in reef health. Local human communities that engage in deforestation, generate high amounts of pollution, or depend largely on fish catches for sustenance have the potential to cause harm to nearby reefs. Although both reefs are situated within the boundaries of the MPA, the proximity of Sampela to activity from villages on Kaledupa has resulted in increased sedimentation and structural damage. The two reefs show clear differences in water clarity (figures 2 versus 3). Mangrove removal near Sampela has likely contributed to the heavy sediment load in the water and on the corals. Sedimentation, in turn, affects reef composition and the types of hard coral genera that can survive. Table 1: Description of categories used in benthic surveys Category HC (Hard Coral) SC (Soft Coral) SPG (Sponge) ALG (Algae) DC ((Dead Coral)) R (Rubble) RK (Rock) S (Sand) OTH (Other) The Wakatobi Marine National Park of South East Sulawesi, Indonesia is the second largest marine national park in Indonesia, covering an area of 1.39 million hectares p y et al., 2007). Within the MPA of the park, two reef sites of differing human p g (Haapkylä interaction were compared in order to determine if local communities have an affect on hard coral cover and hard coral diversity. Description All living, hard coral material All corals without a calcium carbonate skeleton All living member of the phylum Porifora Only macroalgae; encrusting algae found on DC or R was recorded as the substrate Recentlyy killed and white with no ppolyps yp or covered in algae g with the coral skeleton Unconsolidated dead coral pieces Large rock boulders and dead coral which retains no coral characteristics Small, loose rock debris Other biotic reef materials Sediment affects reef communities by blocking sunlight, which is necessary for coral growth, and by coating the coral polyps, which can cause suffocation. As figure 2 shows, massive and submassive corals can survive in high impact areas. These morphologies have corallites (the skeletal cup in which the living polyp resides) located on all sides of the coral, not just the upward side. In contrast, tabulate corals, which have flat upward j p p surfaces, do not survive well in high sediment environments, because the sediment settles directly on the majority of corallites, killing the coral. Sampela was characterized by lone or few hard corals, which were surrounded by rock, sand, rubble, or dead coral (Figures 2 and 4). Pak Kasims had rich communities with hard coral surrounded by macroalgae, soft coral, and sponges with very little dead material (Figures 3 and 4). METHODS This research was conducted at the Operation Wallacea marine research station situated on Hoga Island, a small island located in the Wakatobi Marine National Park (5°27.6`S 123°45.9`) (Figure 1). The data were collected using SCUBA from mid‐July to mid‐August 2008 between the hours of 9:00‐11:00 and 15:00‐17:00. RESULTS Figure 2. Figure 2 Various photos of the high Various photos of the high impact site, Sampela. Note the transect tape in the second photo. Pak Kasims, the low impact site, had a significantly higher percentage of hard coral cover in all three reef zones (p < 0.0001) (Figure 4‐A) than did Sampela, the high impact site. Hard coral cover was greater on the crest and slope than on the flat at both reefs (p = 0.0187) (Figure 4‐A). What the Sampela site lacked in terms of hard coral cover, is mirrored by the high percent cover of dead coral and rubble (Figure 4‐B). Overall, Pak Kasims i d b th hi h t fd d l d bbl (Fi 4 B) O ll P k K i showed a larger h d l percent cover of living reef material (Figure 4‐A and 4‐C), while Sampela showed greater amounts of dead coral and abiotic material (figure 4‐B and 4‐D). Pak Kasims had slightly greater diversity of hard coral genera than Sampela (19 vs. 16) and nearly three times more individuals (Table 2). If all rare genera (5 of fewer individuals) were excluded from the count, Pak Kasims would show more than three times as many genera as Sampela (10 versus 3). 45 A) Hard Coral B) Dead Coral‐Rubble 70 Sampela (High Impact) (High Impact) 40 a 60 35 a Reef p <0.0001 Zone p=0.0187 30 25 50 b Reef p= 0.0002 30 15 20 10 Percent Covver 5 Two sites were selected based on level of disturbance and accessibility. The high i impact site, Sampela, is approximately 1.2 miles from Hoga t it S l i i t l 1 2 il f H I l d ith ill Island, with a village located l t d nearby (note the proximity of the site to the island of Kaledupa in Figure 1 E). The villagers fish the site extensively and have mined coral in the past. In addition, mangrove removal nearby has resulted in increased sedimentation. These factors result in high levels of suspended solids and low light penetration. The depth of the reef flat ranges from 0.5‐2.0 meters and the slope drops down to approximately 11 meters. 10 0 Crest Slope 0 Flat Crest C) Soft Coral‐Sponge‐Algae 45 Reef p= 0.0141 40 Flat 35 35 30 30 25 y g g Coral reef health was assessed by determining hard coral cover and hard coral genus composition and diversity. Coral cover was assessed visually by recording the percentage of the categories as defined in Table 1. Only hard coral was identified to genus. 10 25 Slope D) Rock‐Sand‐Other The low impact site, Pak Kasims, is located off of Hoga Island, approximately 0.2 miles from shore (Figure 1 E). Some fishing occurs here, as well as activity from the research station and the tourist resort nearby. The depth of the reef flat ranges from 0.5‐2.3 meters, and the slope drops down to approximately 30 meters. Slope surveys were not conducted beyond a depth of 12 meters. 20 b Reef p= 0.0003 Zone p= 0.0017 a a 20 15 15 10 5 5 0 0 Crest Slope Flat Table 2. Hard coral genera recorded at each reef site. Italicized numbers represent genera for which >5 individuals were identified. Unknown coral genera were any coral that could not be identified coral that could not be identified. Pak Kasims (Low Impact) 40 20 Figure 1: Location of Pak Kasims and Sampela study sites near Hoga Island, off the Indonesian islands known as the Wakatobi chain (Haapkylä et al. 2007). The presence or absence of particular genera, their relative abundances, and their specific growth forms also support the hypothesis that sedimentation is an important differentiating factor between sites. At Sampela, only one genus (Porites), a massive coral, had more than 7 individuals total (Table 2). Favia (5 individuals), Diploastrea (5 individuals), and Favites (5 individuals) were also found in their massive forms at Sampela. A second growth form was observed at Sampela in the solitary mushroom coral Fungia (7 individuals), which had a single polyp, disk morphology that prevented Figure 3 Various photos of the low Figure 3. Various photos of the low suffocation by sediment. At Pak Kasims, a greater variety of growth forms was observed. suffocation by sediment At Pak Kasims a greater variety of growth forms was observed impact site, Pak Kasims. Note the For example, branching forms of Acropora, (seen behind the massive Porites with the transect tape in the first two blue sea star in Figure 3), was found in high abundance (Table 3). photos. Lastly, because fishing is permitted at the Sampela reef site, anchor damage also has likely broken many hard coral colonies, which contributes to coral rubble (Figure 4‐B) Crest Slope Flat Figure 4 A‐D. Comparison of percent cover by benthic category, for both reef site as a whole and for reef zone. Statistically significant p‐values (< 0.05) are shown for each category. Non‐significant tests of main effects and interactions (p > 0.0390) were not reported. Error bars represent ± 1 S.E.M. Lowercase letters above bars denote post‐hoc Student’s T comparisons between reef zones. A different letter denotes a significant difference. Thus, in both A and D, the crest and slope differ significantly from the flat, but the crest and slope do not differ significantly from each other. Genus Acropora Alveopora Diploastrea Euphyllia Favia Favites Fungia Goniastrea Goniopora Heliopora Herpolitha Lobophyllia Millepora Montipora Mycedium Pachyseris Pectinia Plerogyra Pocillopora Porites Stylophora Tubastrea Unknown Total Genera Total Individuals Pak Kasims Sampela 65 3 28 0 10 5 0 2 10 5 15 5 21 7 2 1 6 7 0 2 2 1 0 3 1 3 4 1 3 0 9 3 2 0 5 0 9 2 152 48 1 0 1 0 16 14 19 16 381 128 GLOBAL CONTEXT and CONCLUSION Mounting evidence indicates that MPAs are effective in protecting coral reefs. A similar study by one of the co‐authors (CRV) compared hard coral cover and genus diversity between between an MPA and a regularly fished site near Ifaty, Madagascar. In terms of live coral an MPA and a regularly fished site near Ifaty Madagascar In terms of live coral cover, the MPA showed a much higher percent cover than did the fished site. However, the fished site showed more genera than the MPA. This can be partially explained by the fact that the MPA was largely covered by a climax community of Montipora foliose. Presumably, the dominance of this coral species prevents new colonies from becoming established but keeps the hard coral coverage percentage high. Together, these studies suggest that survival of hard coral can be greatly increased by protection in MPAs and minimization of anthropogenic disturbance. Diversity, however, while high in MPAs, also depends on the location of the reef and its interplay with the surrounding environment. These two examples show that MPAs do prevail in keeping the benthic cover dominated by living matter. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was supported by the Environmental Science and Policy Program of Smith College, the B. Elizabeth Horner Fund, and the Smith College Praxis summer internship ‐ funding program. In addition, this research would not have been possible had it not been for the Operation Wallacea Conservation Organization, specifically the coral reef monitoring staff on Hoga. REFERENCES Bryant, D. et al. Reefs at Risk. USA: World Resources Institute, 1998 J. Haapkylä et al. Coral disease prevalence and coral health in the Wakatobi Marine Park, south‐east Sulawesi, Indonesia. United Kingdon: Marine Biology Associates, 2007