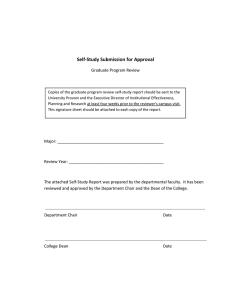

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY SELF-STUDY Prepared for the Middle States Commission on

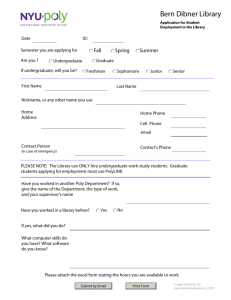

advertisement