3G M P : T

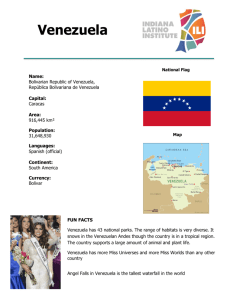

advertisement