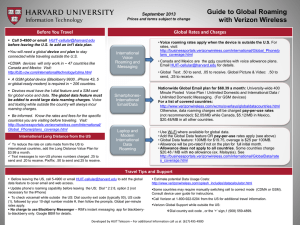

I n t e r n a t I o... RegulatoRy and maRket enviRonment

advertisement