Lessons Learned From PEPFAR S A Mark Dybul, MD

advertisement

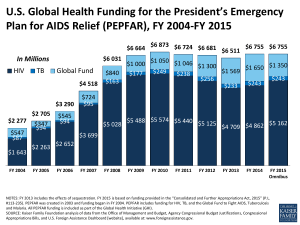

SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE Lessons Learned From PEPFAR Mark Dybul, MD Abstract: The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), launched by President Bush with strong bipartisan support, was a historic moment in development both in size and scope. With $18.8 billion across its first 5 years, it is the largest international health initiative in history for a specific disease. In scope, it is the first global initiative to tackle a chronic disease and was based in a new philosophical foundation centered in country ownership, a results-based accountable approach, the engagement of all sectors, and good governance. With resources and a strong intellectual base, PEPFAR saved lives and provided lessons learned for effective development. Key Words: AIDS, HIV, PEPFAR (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52:S12–S13) T he Lancet recently called the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) ‘‘the largest and most successful bilateral HIV/AIDS program worldwide.’’1 With an initial commitment of $18.8 billion over 5 years, the program set ambitious prevention, care, and treatment goals—to support treatment for 2 million persons, the prevention of 7 million new infections, and care for 10 million, including orphans and vulnerable children. On World AIDS Day 2008, then-president Bush announced that the treatment and care goals he had set had been met ahead of schedule and that the 2010 prevention goal was on track. In July 2008, with strong bipartisan support—including from then-senators Obama, Biden, and Clinton—the law authorizing PEPFAR was renewed at a staggering level of $48 billion for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, with $39 billion for HIV/AIDS. The funding for what was already the largest international health initiative in history for a single disease more than doubled. Looking forward, it is important to consider the components of the success of PEPFAR’s first 5 years. Many details contributed, among them bureaucratic processes that will not be addressed here, where the focus will be on the From the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, Washington, DC. Data presented: Not applicable. Sources of support: None. Correspondence to: Mark Dybul, MD, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Georgetown University Law Center, 1340 Wallach Place, NW, Washington, DC 20009 (e-mail: mrd54@law.georgetown. edu). Copyright ! 2009 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins S12 | www.jaids.com underlying conceptual framework that promoted success. PEPFAR’s innovative programmatic approach was rooted in a historic global commitment on development, the Monterrey Consensus,2 and the fundamental principles it articulated. The first and defining principle is country ownership, and effective country ownership requires good governance, a results-based approach with accountability, and the engagement of all sectors. These principles were further refined and delineated in the Paris Declaration3 and the Accra Accord.4 Country ownership begins with a belief in the dignity and worth of every human life and respect for, and trust in, the people of every country to design and implement successful programs. These truths would seem to be self-evident. But much of development had been based in concepts of ‘‘donors’’ and ‘‘recipients’’ and a paternalistic approach that those from the north and west were coming to ‘‘help’’ poor uneducated people. There was even a prevalent belief that it was not possible for Africans to develop the comprehensive chronic care programs needed for HIV prevention, treatment, and care. PEPFAR created what the New York Times called a ‘‘philosophical revolution’’ by definitively shattering the notion that developing countries could not effectively lead and implement complex chronic care programs.5 Nearly 90% of PEPFAR’s implementing partners are local organizations, and PEPFAR’s success is, in the end, the success of the people in the countries whom the American people are privileged to support. President Paul Kagame of Rwanda put it well when he discussed the fundamental difference in this approach to development—for the first time, countries were being held to high standards, and leaders and countries responded to that respect and trust by achieving goals early and on budget. Those high standards included a focus on results, with strong accountability measures and an expectation of good governance. When PEPFAR began, there was actually criticism that there were preestablished goals and that development efforts could not be reduced to numeric targets. But the goals and focus on results were fundamental to the success of the program. They kept individuals and programs focused and drove an on-the-ground response to achieve them. The goals themselves had important ripple effects, including the establishment of monitoring and evaluation systems required for reporting. It was at the HIV clinic at McCord Hospital in Durban, South Africa, that the first computerized monitoring system was established to report on results. Noticing that nonpregnant women with an elevated mean body mass who were receiving stavudine were developing lactic acidosis, clinicians were able to identify every woman at risk in the clinic, and after their treatment was modified, the phenomenon disappeared. The HIV clinic’s J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr ! Volume 52, Supplement 1, November 1, 2009 J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr ! Volume 52, Supplement 1, November 1, 2009 monitoring system was so clinically useful that the entire hospital adopted it. However, there is always room for improvement. The ultimate goal of antiretroviral therapy is to decrease morbidity and mortality. The number of persons receiving therapy is an output that predicts to some degree these ultimate outcomes, but an evaluation of the morbidity and mortality is needed. Early independent analysis shows 1 million lives saved in just 3 years by treatment alone, but ongoing study is needed.7 Although ‘‘infections averted’’ is an outcome measure, evaluating changes in gender norms is important for assessing the overall impact of prevention programs. The past several years saw the beginning of a process to establish a continuum of indicators from planning to outputs to outcomes and impact. But there is no doubt that a results base with strong accountability was a key factor in the success of PEPFAR, not only in addressing issues relating to HIV but also in strengthening the monitoring and evaluation of health systems and, therefore, in facilitating development overall. The final principle is an essential component of country ownership—the engagement of all sectors. A country cannot be reduced to its government. Government engagement and leadership are essential, and only governments can set national guidance and norms. But the private sector and nongovernmental organizations, including faith-based and communitybased organizations, also have important roles. No health program can be successful unless the community and its leaders are engaged, particularly when behavior change is required. Available data indicate that health outputs improve when the community is involved: Utilization of services increases and loss to follow-up decreases.6 When the private sector contributes its expertise, innovative solutions to problems emerge. In PEPFAR, 80% of partners are nongovernmental organizations and 23% are faith-based organizations. PEPFAR was a leader in public–private partnerships, including perhaps the most significant new effort in prevention in decades—the Partnership for an HIV-Free Generation— which injects the unparalleled expertise of the private sector in q 2009 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Lessons Learned From PEPFAR reaching youth and promoting behavior change. In the end, the heart of PEPFAR was supporting the people of a country to tackle their problems—not just the government but people from all sectors. And the empowerment of all sectors was at the heart of PEPFAR’s success. The fundamental principles of PEPFAR’s success are the fundamental principles of a new era in development. As we look to the next 5 years, it is important to draw on these successes and acknowledge the countless opportunities for improvement. If we maintain the focus on country ownership, a results-based approach and accountability, good governance, and the engagement of all sectors, and if the resource commitments are met, everything is possible. REFERENCES 1. Appointment of PEPFAR head should be merit based [editorial]. Lancet. 2009;373:354. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60112-4. 2. The Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development: The Final Text of Agreements and Commitments Adopted at the International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey Mexico, 18–22 March 2002. New York, NY: United Nations; 2003. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/monterrey/MonterreyConsensus. pdf. Accessed May 16, 2009. 3. Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness: Ownership, Harmonization, Alignment, Results, and Mutual Accountability. Presented at: The HighLevel Forum on Aid Effectiveness; February 28–March 2, 2005; Paris, France. Available at: http://www1.worldbank.org/harmonization/paris/ finalparisdeclaration.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2009. 4. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Accra Accord. Resolutions of UNCTAD XII. Accra, Ghana: United Nations; 2008. Available at: http://www.unctad.org/en/docs//tdxii_accra_accord_en.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2009. 5. Stolberg SG. In global battle on AIDS, Bush creates legacy. New York Times. January 5, 2008. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/05/ washington/05aids.html?fta=y. Accessed May 16, 2009. 6. World Health Organization Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 2009;373:2137–2169. doi:10.1016/S01406736(09)60919-3. 7. Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in Africa: evaluation of outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;688–695. www.jaids.com | S13