Sensitivity to Verb Bias in ASL‐English bilinguals Verb biases have been shown to help native English readers resolve temporary ambiguity in sentence comprehension. When a post‐verbal constituent may either be a

advertisement

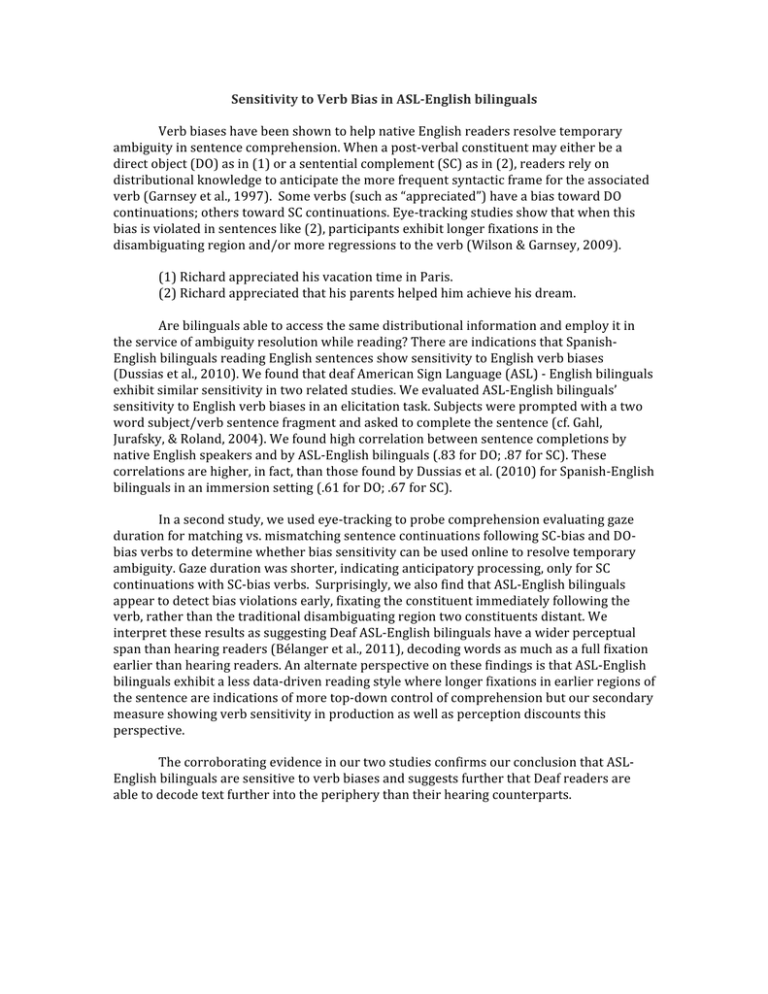

Sensitivity to Verb Bias in ASL‐English bilinguals Verb biases have been shown to help native English readers resolve temporary ambiguity in sentence comprehension. When a post‐verbal constituent may either be a direct object (DO) as in (1) or a sentential complement (SC) as in (2), readers rely on distributional knowledge to anticipate the more frequent syntactic frame for the associated verb (Garnsey et al., 1997). Some verbs (such as “appreciated”) have a bias toward DO continuations; others toward SC continuations. Eye‐tracking studies show that when this bias is violated in sentences like (2), participants exhibit longer fixations in the disambiguating region and/or more regressions to the verb (Wilson & Garnsey, 2009). (1) Richard appreciated his vacation time in Paris. (2) Richard appreciated that his parents helped him achieve his dream. Are bilinguals able to access the same distributional information and employ it in the service of ambiguity resolution while reading? There are indications that Spanish‐ English bilinguals reading English sentences show sensitivity to English verb biases (Dussias et al., 2010). We found that deaf American Sign Language (ASL) ‐ English bilinguals exhibit similar sensitivity in two related studies. We evaluated ASL‐English bilinguals’ sensitivity to English verb biases in an elicitation task. Subjects were prompted with a two word subject/verb sentence fragment and asked to complete the sentence (cf. Gahl, Jurafsky, & Roland, 2004). We found high correlation between sentence completions by native English speakers and by ASL‐English bilinguals (.83 for DO; .87 for SC). These correlations are higher, in fact, than those found by Dussias et al. (2010) for Spanish‐English bilinguals in an immersion setting (.61 for DO; .67 for SC). In a second study, we used eye‐tracking to probe comprehension evaluating gaze duration for matching vs. mismatching sentence continuations following SC‐bias and DO‐ bias verbs to determine whether bias sensitivity can be used online to resolve temporary ambiguity. Gaze duration was shorter, indicating anticipatory processing, only for SC continuations with SC‐bias verbs. Surprisingly, we also find that ASL‐English bilinguals appear to detect bias violations early, fixating the constituent immediately following the verb, rather than the traditional disambiguating region two constituents distant. We interpret these results as suggesting Deaf ASL‐English bilinguals have a wider perceptual span than hearing readers (Bélanger et al., 2011), decoding words as much as a full fixation earlier than hearing readers. An alternate perspective on these findings is that ASL‐English bilinguals exhibit a less data‐driven reading style where longer fixations in earlier regions of the sentence are indications of more top‐down control of comprehension but our secondary measure showing verb sensitivity in production as well as perception discounts this perspective. The corroborating evidence in our two studies confirms our conclusion that ASL‐ English bilinguals are sensitive to verb biases and suggests further that Deaf readers are able to decode text further into the periphery than their hearing counterparts.