Document 12886774

advertisement

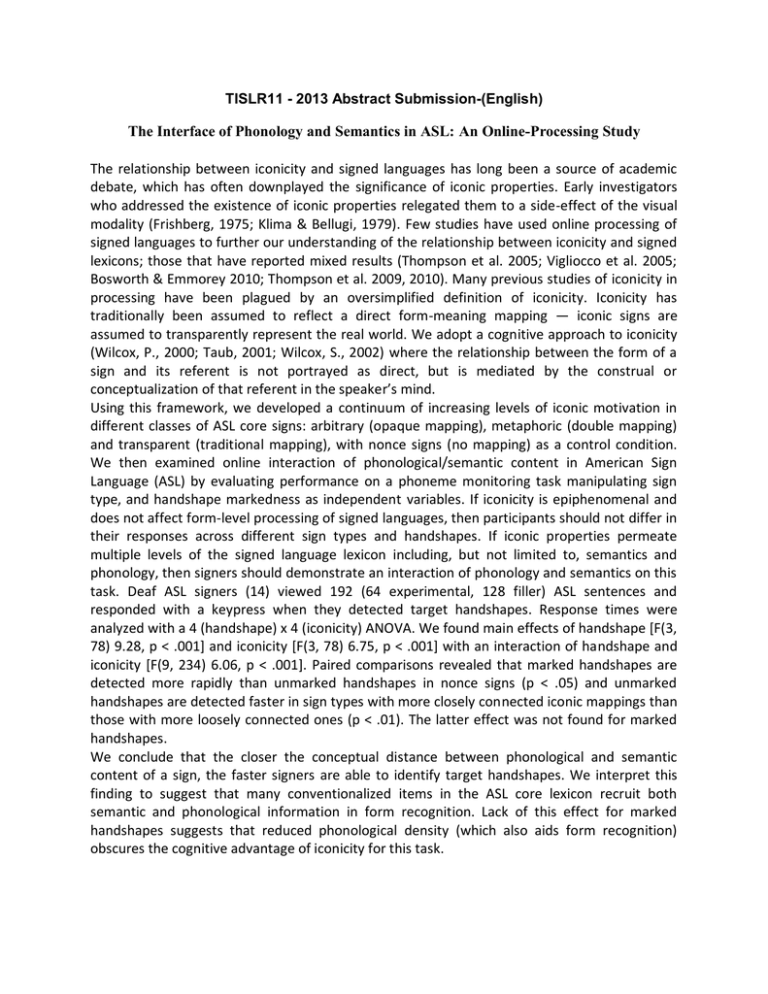

TISLR11 - 2013 Abstract Submission-(English) The Interface of Phonology and Semantics in ASL: An Online-Processing Study The relationship between iconicity and signed languages has long been a source of academic debate, which has often downplayed the significance of iconic properties. Early investigators who addressed the existence of iconic properties relegated them to a side-effect of the visual modality (Frishberg, 1975; Klima & Bellugi, 1979). Few studies have used online processing of signed languages to further our understanding of the relationship between iconicity and signed lexicons; those that have reported mixed results (Thompson et al. 2005; Vigliocco et al. 2005; Bosworth & Emmorey 2010; Thompson et al. 2009, 2010). Many previous studies of iconicity in processing have been plagued by an oversimplified definition of iconicity. Iconicity has traditionally been assumed to reflect a direct form-meaning mapping — iconic signs are assumed to transparently represent the real world. We adopt a cognitive approach to iconicity (Wilcox, P., 2000; Taub, 2001; Wilcox, S., 2002) where the relationship between the form of a sign and its referent is not portrayed as direct, but is mediated by the construal or conceptualization of that referent in the speaker’s mind. Using this framework, we developed a continuum of increasing levels of iconic motivation in different classes of ASL core signs: arbitrary (opaque mapping), metaphoric (double mapping) and transparent (traditional mapping), with nonce signs (no mapping) as a control condition. We then examined online interaction of phonological/semantic content in American Sign Language (ASL) by evaluating performance on a phoneme monitoring task manipulating sign type, and handshape markedness as independent variables. If iconicity is epiphenomenal and does not affect form-level processing of signed languages, then participants should not differ in their responses across different sign types and handshapes. If iconic properties permeate multiple levels of the signed language lexicon including, but not limited to, semantics and phonology, then signers should demonstrate an interaction of phonology and semantics on this task. Deaf ASL signers (14) viewed 192 (64 experimental, 128 filler) ASL sentences and responded with a keypress when they detected target handshapes. Response times were analyzed with a 4 (handshape) x 4 (iconicity) ANOVA. We found main effects of handshape [F(3, 78) 9.28, p < .001] and iconicity [F(3, 78) 6.75, p < .001] with an interaction of handshape and iconicity [F(9, 234) 6.06, p < .001]. Paired comparisons revealed that marked handshapes are detected more rapidly than unmarked handshapes in nonce signs (p < .05) and unmarked handshapes are detected faster in sign types with more closely connected iconic mappings than those with more loosely connected ones (p < .01). The latter effect was not found for marked handshapes. We conclude that the closer the conceptual distance between phonological and semantic content of a sign, the faster signers are able to identify target handshapes. We interpret this finding to suggest that many conventionalized items in the ASL core lexicon recruit both semantic and phonological information in form recognition. Lack of this effect for marked handshapes suggests that reduced phonological density (which also aids form recognition) obscures the cognitive advantage of iconicity for this task. References Bosworth, R. G., & Emmorey, K. (2010). Effects of iconicity and semantic relatedness on lexical access in american sign language. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 1573–1581. doi:10.1037/a0020934Brentari, D. (1998). A Prosodic model of sign language phonology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Emmorey, K. (2002). Language, cognition and the brain: Insights from sign language research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Frishberg, N. (1975). Arbitrariness and Iconicity: Historical Change in America. Language, 51(3), 696-719. Klima, E. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press. Orlansky, M., & Bonvillian, J. (1984). The Role of Iconicity in Early Sign Language Acquisition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 49(3), 287-292. Taub, S. (2001). Language from the body. Cambridge ;;New York ;;Melbourne [etc.]: Cambridge University press. Thompson, R., Emmorey, K., & Gollan, T. (2005). “Tip of the Fingers” Experiences by Deaf Signers: Insights into the Organization of a Sign-Based Lexicon. Psychological Science, 16(11), 856-860. Thompson, R. L., Vinson, D. P., & Vigliocco, G. (2009). The link between form and meaning in American Sign Language: Lexical processing effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 550-557. doi:10.1037/a0014547 Thompson, R., Vinson, D., & Vigliocco, G. (2010). The Link between Form and Meaning in British Sign Language: Effects of Iconicity for Phonological Decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(4), 1017-1027. doi:10.1037/a0019339 Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D., Dye, M., & Woll, B. (2005). Language and Imagery: Effects of Language Modality. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, 272(1574), 1859–1863. Wilcox, P. (2000). Metaphor in American Sign Language. Washington D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. Wilcox, S. (2004). Conceptual spaces and embodied actions: Cognitive iconicity and signed languages. Cognitive Linguistics, 15(2), 119-147.