Iconicity in language (3 projects)

advertisement

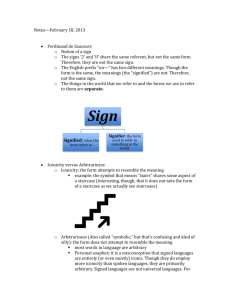

What’s in a name? Iconicity in language Gabriella Vigliocco, Matthew Jones (Institute for Multimodal Communication, UCL) Three projects focus on iconicity (resemblance/transparency between form and meaning; Perniss, Thompson & Vigliocco, 2010). We know that certain sounds evoke certain shapes across cultures and languages (e.g. 'kiki' sounds spiky and 'bouba' sounds round; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001), and that people pick the meaning of words in a completely unknown language at above chance (Imai et al., 2008). This suggests that iconicity is present in natural language (perhaps because iconic words appear to be easy to learn; Monaghan, Mattock, & Walker, 2012). We will provide programs, materials, and support during the running of the experiments and the analysis of the results. There is also the possibility to assist in developing, conducting imaging studies of iconicity. The students will be required to begin working on the project from November and to attend weekly lab meetings where they will also present their work. Project 1: Iconicity and the Cultural Evolution of Language To explore how iconicity comes about, we use a paradigm called iterated learning (IL; Kirby, Cornish, & Smith, 2008). This is a lab model of cultural evolution – Darwinian change on the level of culture, with more learnable words emerging and being passed on to further generations (participants). It works like the children’s game of ‘broken telephone’. A first participant is taught a simple arbitrary pseudolanguage of names for visual stimuli featuring different shapes. The participant is tested, and these names are then taught to a second participant (along with any errors), whose own responses are taught to a third. This process goes on for ten participants (or 'generations'). The language evolves towards greater learnability over time. Our previous experiments have shown the emergence of kiki-bouba like sound-shape iconicity in text-based IL (Jones et al., 2014). One MSc student will work on iterated learning experiments that aim to see whether iconicity emerges when words are spoken rather than written, and whether iconicity emerges in gesture when the IL methodology is extended to the visual domain. Project 2: Iconicity and word learning Are some words easier to learn for some meanings? Moreover, could gestures produced by speakers also be integrated and used in learning? In this project we will employ the cross-situational learning paradigm (an ecologically valid learning paradigm based on statistical co-occurrence; Yu & Smith, 2007) to assess: 1) How much is word learning improved when auditory input is accompanied by iconic gesture? 2) Some word sounds seem iconic for certain shapes (e.g. ‘kiki’ sounds spiky, bouba ‘round’ across languages and cultures; Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001). Why is this? We will focus on finegrained differences between speech sounds, and on manipulations affecting the salience of mouth shape, to see what helps make a word for a shape more or less learnable. This will test the hypothesis that iconicity is the result of cross-modal associations between ‘round’ sounds and round mouth shapes, as suggested by previous work showing that the round association is stronger than the spiky (Jones et al., 2014). Project 3: Creating new names for referents, and new referents for names If iconicity makes words more learnable, will people (1) tend to use it when generating new labels for new objects (e.g., giving a name such as moma to a roundish shape)? And also, (2) tend to infer properties of objects from the name (e.g., assuming a roundish object when given a name such as moma?) During a summer exhibit at the Science Museum we have collected data from >600 museum visitors, including both children and adults (age from 4 to 80) and different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Our MSc student will assist us in the scoring and analysis of this massive data set, using detailed phonetic analysis of speech as well as sophisticated visual analysis of drawings produced by participants. Imai, M. Kita, S., Nagumo, M., and Okada, H. (2008). Sound symbolism facilitates early verb learning. Cognition 109, 54–65. Jones, M., Vinson, D., Clostre, N., Zhu, A. L., Santiago, J., & Vigliocco, G. (2014). The bouba effect: sound-shape iconicity in iterated and implicit learning. Proceedings of the 36th Annual meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 2459-64. Kirby, S., Cornish, H., & Smith, K. (2008). Cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory: An experimental approach to the origins of structure in human language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(12), 5241-5245. Monaghan, P., Mattock, K., & Walker, P. (2012). The role of sound symbolism in word learning. Journ Exp Psych: Learn Mem Cog 38, 1152-1164. Perniss, P., Thompson, R. L., & Vigliocco, G. (2010). Iconicity as a general property of language: evidence from spoken and signed languages. Frontiers in Psychology 1(227), Published online (http://www.frontiersin.org/Language_Science/). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00227 Ramachandran, V. S. & Hubbard E. M. (2001). Synesthesia: a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(12), 3-34. Yu, C., & Smith, L. (2007). Rapid word learning under uncertainty via cross-situational statistics. Psychological Science, 18(15), 414–420.