Patient Complaints and Adverse Surgical Outcomes Article 584158

advertisement

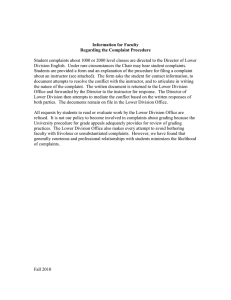

584158 research-article2015 AJMXXX10.1177/1062860615584158American Journal of Medical QualityCatron et al Article Patient Complaints and Adverse Surgical Outcomes American Journal of Medical Quality 1­–8 © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1062860615584158 ajmq.sagepub.com Thomas F. Catron, PhD1, Oscar D. Guillamondegui, MD, MPH1, Jan Karrass, MBA, PhD1, William O. Cooper, MD, MPH1, Barbara J. Martin, RN, MBA, CCRN1, Roger R. Dmochowski, MD1, James W. Pichert, PhD1, and Gerald B. Hickson, MD1 Abstract One factor that affects surgical team performance is unprofessional behavior exhibited by the surgeon, which may be observed by patients and families and reported to health care organizations in the form of spontaneous complaints. The objective of this study was to assess the relationship between patient complaints and adverse surgical outcomes. A retrospective cohort study used American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data from an academic medical center and included 10 536 patients with surgical procedures performed by 66 general and vascular surgeons. The number of complaints for a surgeon was correlated with surgical occurrences (P < .01). Surgeons with more patient complaints had a greater rate of surgical occurrences if the surgeon’s aggregate preoperative risk was higher (β = .25, P < .05), whereas there was no statistically significant relationship between patient complaints and surgical occurrences for surgeons with lower aggregate perioperative risk (β = −.20, P = .77). Keywords patient complaints, quality, safety, professionalism In an era of increased focus on safety and quality in health care, health systems are placing greater emphasis on understanding, identifying, and addressing threats to reliable care delivery. In many health care settings, particularly in surgery, reliability is dependent on well-functioning teams, wherein professionals are required to monitor multiple events and tasks at critical points in the patient’s treatment and must interact in a way that optimizes each member’s contributions.1-4 One factor that may affect surgical team behavior is the level of professionalism displayed by the surgeon. In addition to cognitive and technical competence, surgeons are expected to model behaviors that enhance team performance, including clear and effective communication, being available, modeling respect, and having awareness of how their performance influences team performance.2,5-8 Unprofessional behaviors, on the other hand, undermine a culture of safety, threaten teamwork, and have been linked to medical errors and adverse surgical outcomes.1,6-13 Patients and families are well positioned to observe surgeons’ behaviors, and in some cases report their concerns to health system representatives.1,11-23 For example, a patient reporting to a hospital’s patient relations office that her surgeon “told me, ‘you don’t need to know that. Just lay down,’” may be recognizing a behavior that fails to model respect. Another patient who reports, “Dr __ was so mean and rude to my nurse in front of us all. It makes me very nervous to have him come into my room now,” may be perceiving a threat to trust and teamwork. The authors have previously demonstrated that patient complaints are nonrandomly distributed and high complaint numbers are associated with high malpractice claims experience.12-20 The objective of this study was to assess the relationship between patient complaints and adverse surgical outcomes. It was hypothesized that surgeons who generated a greater number of patient complaints about lack of respect, availability, and ineffective communication also might model these same behaviors with members of the surgical team and therefore would have higher occurrences of adverse surgical outcomes. Thus, a study was performed using data from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement 1 Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN Corresponding Author: William O. Cooper, MD, MPH, Center for Patient and Professional Advocacy, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 2135 Blakemore Ave, Nashville, TN 37212-3505. Email: william.cooper@vanderbilt.edu Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 2 American Journal of Medical Quality Program (NSQIP)21,24 linked with an established patient complaint reporting system used previously to study professionalism concerns and malpractice risk.15,22,23 This study sought to further understand whether surgeons with higher aggregate perioperative risk in the cases they performed had a stronger relationship between complaints and surgical outcomes than surgeons with lower aggregate perioperative risk. Methods A retrospective cohort study was performed using spontaneous patient complaint data and ACS NSQIP data from an academic medical center (AMC)21,25 during the period from July 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011. The study site has more than 900 inpatient beds, serves a catchment area of approximately 4.5 million persons, and performs more than 50 000 surgical procedures annually.26,27 The data sets were merged using a unique physician identifier created specifically for this study and known only by 2 data managers, one responsible for the patient complaint data and the other responsible for the NSQIP data. The resulting de-identified database was used for all analyses. The study included all credentialed surgeons with active surgical practices any time during the study period and for whom NSQIP data were available. NSQIP data at the AMC were recorded for members of the Divisions of General Surgery (includes surgeons who treat disorders involving emergency general surgery, advanced laparoscopy, bariatric surgery, oncological surgery, colorectal surgery, and esophageal and pancreatic procedures) and Vascular Surgery (includes surgeons who care for patients with peripheral arterial disease, carotid disease, renovascular disorders, and aneurysm disease of the thorax, abdomen, and extremities). On an 8-day cycle, NSQIP data were abstracted from the first 40 general and vascular surgery cases performed at the AMC that met NSQIP inclusion criteria.28 Three variables were chosen to create a single measure of relative perioperative risk (hereafter “risk”) based on their ability to predict adverse surgical outcomes in previous studies29: American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) classification (1 to 5 range), wound classification (4 levels of contamination), and emergency case status (yes/no).28 Five categories of surgical occurrences were extracted from the NSQIP data set28: intraoperative or perioperative, wound, respiratory, urinary/renal, and other occurrences (see online Appendix 1, available at http://ajmq. sagepub.com/supplemental). Central nervous system occurrences also were assessed, but were rare (<1% of all occurrences) and contributed negligible variance, so were not included in analyses. In addition, beginning January 1, 2011, NSQIP discontinued required counting of coma >24 hours, peripheral nerve injury, graft prosthesis flap failure, and other postoperative occurrences, so these were not included for that year.28 A count of the number of cases sampled by NSQIP auditors for each surgeon was included in analyses to control for disproportionate impact of surgeons with higher or lower volumes. Reports of unsolicited patient and family member complaints were recorded by the medical center’s patient relations staff for all patients who received care from one of the study surgeons during the study period. A validated research database derived from these reports and used in several prior research studies was used to characterize complaints received for each study surgeon.14,15,17,18,20,30 Complaints were attributed to a surgeon only when the surgeon was specifically identified by the patient and the behavior explicitly linked to the surgeon.14,15,17,18,20,30 Independent coders reviewed patient relations reports and reliably (interrater reliabilities of 73% to 100% across categories) assigned unique complaints to general categories22,31 involving issues of care and treatment, communication, respect for patient and/or family, accessibility, and billing. Billing concerns were only included when they described a patient’s concern related to a physician’s interactions. For example, a patient who reports that “I asked legitimate questions and he only gave me smart aleck answers. I should not have to pay to be treated that way” is expressing her or his dissatisfaction with the care rather than disputing a specific issue related to billing. Reports recorded during the study period that included complaints about uniquely identified physicians were used. To focus on behaviors that would be most likely to affect teamwork and influence quality outcomes, complaint statements about care and treatment were excluded from the analysis, as these complaints have previously been demonstrated to be associated with poor surgical outcomes and are intrinsically related to the outcomes of interest.32 Analyses were performed using surgeons as the unit of analysis. The study size was fixed based on the available data from NSQIP and the patient complaints database. In order to minimize the number of variables, the mean across each physician’s sampled cases was entered into a principal components analysis to assign risk for an individual physician across his or her proportion of the sample cases.33 The resultant score defined that physician’s average patient-related perioperative risk. The analysis set the group means at zero; higher scores indicated greater perioperative risk than lower scores. Multilevel models using full information maximum likelihood were employed to predict the slope of surgical occurrences. This 2-step technique has the advantage of using continuous variables, rather than discrete variables, as part of an interaction. In the first step, the cumulative measures of perioperative risk factors and patient Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 3 Catron et al complaints were centered on their respective sample means to reduce nonessential multicollinearity among interaction terms. For example, the mean number of patient complaints across physicians was subtracted from each value creating a new, centered variable with a mean of zero. Centering the variables assured that the interaction term was not highly correlated with the main effect variables.33 For the purposes of this study, uncorrelated measures of risk and patient complaints were selected to permit the best examination of the study hypotheses.33 To test the hypothesis that patient complaints differentially predict surgical occurrences for surgeons across 2 continua of risk, one high and one low, an interaction term was created by multiplying the centered patient complaints variable with the perioperative risk variable. As recommended by Aiken and West,33 for examining high risk, each surgeon’s perioperative risk score was transformed by increasing it by one standard deviation; for examining low risk, one standard deviation was subtracted from each surgeon’s risk score. These algebraic transformations were used to assess patterns at the upper and lower levels of performance, and significant interaction terms would indicate that perioperative risk moderated the relationship between patient complaints and each type of surgical occurrence. SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used for all analyses. Missing data were rare. NSQIP performs regular quality audits and provides opportunities for data correction. In addition, the variables used for this study have forced data entry to reduce missing data. For a small proportion (<1.5%) of surgical cases, follow-up for 30-day occurrences was not available (eg, an acute appendectomy with a 2-week follow-up visit and no subsequent encounters). For the purposes of this study, occurrences were included for cases with <30-day follow-up using the latest data available. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (#111064) approved the study and determined that it satisfied the criteria for exemption from full review and approved the waiver of informed consent. Results Sixty-six surgeons (59 in General Surgery and 7 in Vascular Surgery) met inclusion criteria and performed a total of 10 536 NSQIP-abstracted procedures (median = 92). The mean age of the study surgeons was 46.2 years (Table 1); 82% were males, and nearly all completed medical school and postgraduate training in the United States. On average, the study surgeons had been in practice 11.7 years. Study surgeons had between 0.5 and 6.5 years of surgical data and complaint reports in the research database; 36 (55%) had 4 or more complete years of data. Table 1. Characteristics of the Surgeons (n = 66). Mean age (years) Mean years of post-residency experience Female gender US medical school graduate Postgraduate training in United States Board certified in specialty 46.2 years 11.7 years 18% 88% 100% 92% Study surgeons generated a mean 7.98 patient complaints during the study period (Table 2). The most frequent patient complaints related to communication and accessibility. Forty-three percent of surgeon-associated patient/family complaints resulted from concerns about outpatient encounters, 41% from inpatient experiences, and 3% from observations made during emergency department experiences; 13% of complaint-associated locations were not reported. On average, study surgeons had 159.6 cases sampled during follow-up. The most frequent surgical occurrences were respiratory complications and wound infections. Intraoperative occurrences and urinary occurrences occurred less frequently. Demographic data about the patients whose surgical experiences were captured for this study are presented in online Appendix 2 (available at http://ajmq.sagepub.com/ supplemental). Compared with all patients in the national NSQIP database, those in the present study were younger, more likely to be female, and less likely to be members of racial minority groups. The number of patient complaints for an individual surgeon was significantly correlated with all surgical occurrence categories (range of Pearson’s correlations: rs = .55-.61, P < .001; Table 3). No correlations between patient complaints and a surgeon’s perioperative risk, ASA class, priority status, or wound classification were statistically significant. In hierarchical regression analyses (Table 4), the number of cases sampled, a proxy for volume of service, was a significant predictor of all 5 categories of occurrences when controlling for perioperative risk and patient complaints (Table 4, Step 1: βs = .57 to .77, all P < .0.01). Perioperative risk predicted respiratory and wound occurrences, over and above the effects of the number of cases, such that surgeons whose patients presented with higher risk were associated with more occurrences in these categories (Table 4, Step 1: βs = .27 and .22, respectively, P < .05). Addition of the interaction between perioperative risk and patient complaints to the model significantly increased the fit of the 4 occurrence-specific models (Table 4, Step 2: βs = .20 to .29, P < .05). The interaction between perioperative risk and patient complaints was significant for predicting wound Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 4 American Journal of Medical Quality Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations for Surgeons’ Patient Complaints, Perioperative Risk Factors, and Surgical Occurrences. Standard Deviation Mean Median Sum 3.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 6.00 281 96 153 62 527 2.65 0.09 1.00 −0.14 91.50 3.50 6.00 6.50 3.00 8.50 10 536 627 1107 1327 498 1598 Complaints received for a physician during study follow-up (number of complaints) Communication 4.26 4.20 Concern 1.45 1.96 Accessibility 2.32 2.85 Billing 0.94 1.01 Total 7.98 9.41 Surgeon’s aggregate perioperative risk across sampled patients ASA class (1-5) 2.63 0.35 Priority (emergent/nonemergent) 0.18 0.21 Wound class (1-4) 1.05 0.69 Risk score 0.00 1.00 Surgical occurrences (number of occurrences) Cases sampled 159.64 181.87 Intraoperative 9.50 13.34 Wound 16.77 29.52 Respiratory 20.11 30.69 Urinary 7.55 12.02 Other 24.08 36.32 Abbreviation: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology. Table 3. Intercorrelations Among Number of Cases, Surgical Occurrences, Perioperative Risk Factors, and Patient Complaints. Variables 1. Cases sampled 2. Intraoperative 3. Wound 4. Urinary 5. Respiratory 6. Other 7. Perioperative risk score 8. ASA class 9. Priority status 10. Wound class 11. Total complaints 1 .60c .70c .73c .63c .63c −.32b −.01 −.41b −.24d .72c 2 .63c .72c .95c .93c .05 .29a −.07 .02 .58c 3 .92c .69c .78c −.01 .08 −.21d .17 .60c 4 5 .75c .86c −.05 .13 −.24a .07 .61c .90c .07 .24a −.07 .08 .59c 6 −.01 .28a −.17 .02 .55c 7 .48c .92c .87c .12 8 .31a .13 .19 9 10 .71c .00 .16 Abbreviation: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology. a P < .05. b P < .01. c P < .001. d P < .10. occurrences (Figure 1). When a surgeon’s average perioperative risk was increased by one standard deviation, patient complaints were significantly related to wound occurrences, such that surgeons with more patient complaints also experienced more patient wound occurrences (β = .42, P < .05). Conversely, when a surgeon’s average perioperative risk was reduced one standard deviation (ie, representing relatively low risk), patient complaints were not significantly related to wound occurrences; the slope of this line did not differ from zero (β = −.04, P = .77). The slope of the relationship between patient complaints and wound occurrences at average patient perioperative risk was similarly not statistically different from zero. Similar findings were seen for intraoperative and respiratory occurrences, but not for urinary occurrences. Discussion In this study of surgeons from a large, tertiary care AMC, the authors reviewed surgical occurrences for 10 536 surgical cases from 66 surgeons and found that spontaneous Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 5 Catron et al Table 4. Hierarchical Regression Model Predicting Surgical Occurrences From Perioperative Risk and Patient Complaints (Excluding Care and Treatment Complaints). Type of Surgical Occurrence Step and Predictors Urinary Intraoperative Respiratory Wound Other 16.08c .41 .57b .21d .15 19.53c .46 .66c .27a .08 24.49c .52 .74c .22a .05 16.70c .42 .67c .21d .04 4.25a .04 .55b .25a .27 .23a 7.91b .06 .63c .31b .24 .29b 6.72a .05 .71c .26a .19 .25a 3.13d .03 .65c .24a .15 .20d 1: Cases + Risk + Complaints Overall F 28.06c 2 Adjusted R .56 Cases sampled β .77c Perioperative risk score β .19d Patient complaints β .03 2: Cases + Risk + Complaints + Risk × Complaints F (change) 4.34a 2 R (change) .03 .76c Cases sampled β Perioperative risk score β .22a Patient complaints β .14 .20a Perioperative risk × Complaints β a P < .05. P < .01. c P < .001. d P < .10. b Figure 1. Simple slopes of patient complaints as a moderator of wound occurrences at 2 levels of perioperative risk (values adjusted for number of cases sampled). The solid line represents the slope of the relationship between patient complaints and wound occurrences when surgeons’ perioperative risk is increased by one standard deviation (ie, representing patients with high risk). Surgeons with higher risk cases and more complaints experienced significantly more wound occurrences (solid line), but surgeons with lower risk cases and more complaints had no more wound occurrences than those with fewer patient complaints (dotted line). patient complaints about communication, respect, and accessibility were correlated with surgical occurrences and that this relationship was moderated by a surgeon’s aggregate perioperative risk. When surgeons with low aggregate perioperative risk operated, they had the same low rate of NSQIP-defined occurrences regardless of their Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 6 American Journal of Medical Quality case-adjusted numbers of complaints. However, surgeons with the greatest case-adjusted numbers of patient complaints who performed procedures associated with higher mean risk had a greater likelihood of surgical occurrences. These findings suggest that when patients’ experiences with their surgeons were sufficiently concerning to prompt a formal complaint to the organization, the patients may have observed behaviors that also negatively affected a surgery service team’s ability to achieve desired outcomes, especially as complexity, risk, and stress increased. For example, aggregated patient complaints about perceived failures to demonstrate respect toward the patient (eg, “Doctor ____ left our room, walked down the hall and said to the nurse, ‘This patient has completely [fouled] up my day . . . go give him some information and get him out of here’, I heard every word he said about me”) may mirror a physician’s similar behavior toward other medical team members. Although patients and their families rarely observe (and evaluate) the surgeon’s teamwork skills in the operating room, they form impressions during initial and follow-up consultations, interactions on the day of surgery, and during ongoing care the surgeon may provide. Patients’ observations, if documented, aggregated, and analyzed, may facilitate identification of surgeons who model behaviors that not only create patient dissatisfaction but also increase malpractice risk and may have a negative impact on teamwork. Engaging patients who complain about their physicians in these settings as a part of service recovery also can facilitate a 2-way engagement that might identify ways to improve physician behavior and ultimately reduce adverse outcomes. The finding that patient complaints predicted risk for adverse surgical outcomes for surgeons with higher aggregate operative risk and not for surgeons with lower aggregate operative risk is interesting and warrants further consideration. Previous research on teamwork in a variety of settings suggests that the behaviors observed by patients and families and reported to the organization in the form of a complaint may have a stronger impact on teamwork and outcomes when the team’s task requires a greater degree of interdependence. The team member with behaviors that undermine a culture of safety may have an even greater impact on interdependent teams when that individual provides critical skills or expertise that cannot be provided by others.34 Interdependence and team members with critical expertise (ie, surgeons) exist in surgical teams operating in higher risk settings and typically to a greater degree than surgical teams involving lower risk settings. The hierarchy of surgical teams also interferes with a team’s natural moderating of negative behaviors because of a real or perceived power differential among the surgeon and other team members.34 Negative interactions by the surgeon in these higher risk operative settings might therefore result in worsened team performance and higher rates of adverse occurrences because of their impact on individual team members, including team members’ distraction from critical tasks.34 The findings of this study mirror previous studies demonstrating a relationship between spontaneous patient complaints and risk for malpractice claims, patients’ practice dropout, and nonadherence to medical recommendations.12-16,19,24,29,35 In the malpractice claims studies, obstetricians with high claims experience generated 3 times the number of complaints of lower risk obstetricians. Importantly, when physicians with high numbers of patient complaints receive feedback from peers as a part of a structured intervention, their patient complaints typically are reduced.31 The findings also underscore previous observations that technical skills alone are not sufficient to ensure optimal surgical outcomes2,7,9,10—behaviors that promote teamwork are critical to success. There are some study limitations. The data were drawn from a single site, which may limit generalizability. Future studies from multiple institutions will be important to replicate these findings. Complaints from all patients who received care from the surgeon were included, not just the sampled cases. Although it may be true that patients with adverse outcomes may be more likely to complain in general, this study focused on complaints unrelated to care and treatment and focused instead on complaints that might reflect communication, respect, and teamwork. Complaints describing concerns related to care and treatment were intentionally excluded because of the previously reported intrinsic relationship between these types of complaints and outcomes.32 Although the number of sampled cases was controlled for in these analyses, it is possible that the significant correlations between surgical occurrences and aggregated spontaneous complaints may be an artifact of surgeons’ varied volumes of cases, but including number of cases in the analysis should mitigate this effect somewhat. Finally, patients’ complaints were based on experiences before and following surgery; only very rarely did complaints involve observations made during operating room experiences when all or virtually all patients are anesthetized. In conclusion, this study found a significant correlation between patient complaints and surgical occurrences. For surgeons with low-risk surgical cases, high complaint generation did not predict adverse occurrences. However, as surgical complexity rose, adverse occurrences were correlated with patient complaints. These findings have relevance for health care organizations Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 7 Catron et al seeking to promote team performance and outcomes34; these organizations might share complaint data with surgeons to help improve teamwork-related behaviors and outcomes.22,31,36-38 Authors’ Note Thomas F. Catron and Oscar D. Guillamondegui are first coauthors. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Dmochowski worked as a consultant for both Allergan and Medtronic, but the research described in this article did not relate to these relationships. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. References 1. Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core Principles & Values of Effective Team-based Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012. 2. Mazzocco K, Petitti DB, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;197: 678-685. 3. Sexton JB, Paine LA, Manfuso J, et al. A check-up for safety culture in “my patient care area.” Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:699-703. 4. Makary MA, Sexton JB, Freischlag JA, et al. Operating room teamwork among physicians and nurses: teamwork in the eye of the beholder. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202: 746-752. 5.Hickson GB, Moore IN, Pichert JW, Benegas M Jr. Balancing systems and individual accountability in a safety culture. In: Berman S, ed. From the Front Office to the Front Line: Essential Issues for Healthcare Leaders. 2nd ed. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources, Inc.; 2012:1-36. 6. Moran SK, Sicher CM. Interprofessional jousting and medical tragedies: strategies for enhancing professional relations. AANA J. 1996;64:521-524. 7. Catchpole K, Mishra A, Handa A, McCulloch P. Teamwork and error in the operating room: analysis of skills and roles. Ann Surg. 2008;247:699-706. 8.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel Events: Behaviors That Undermine a Culture of Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 2008. 9. Mishra A, Catchpole K, Dale T, McCulloch P. The influence of non-technical performance on technical outcome in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:68-73. 10.Shouhed D, Gewertz B, Wiegmann D, Catchpole K. Integrating human factors research and surgery: a review. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1141-1146. 11. Allsop J. Two sides to every story: complainants’ and doctors’ perspectives in disputes about medical care in a general practice setting. Law Policy. 1994;16:149-183. 12.Cydulka RK, Tamayo-Sarver J, Gage A, Bagnoli D. Association of patient satisfaction with complaints and risk management among emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:405-411. 13. Fullam F, Garman AN, Johnson TJ, Hedberg EC. The use of patient satisfaction surveys and alternative coding procedures to predict malpractice risk. Med Care. 2009;47:553-559. 14.Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Blackford J, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk in a regional healthcare center. South Med J. 2007;100:791-796. 15. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, Miller CS, GauldJaeger J, Bost P. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287:2951-2957. 16. Levtzion-Korach O, Frankel A, Alcalai H, et al. Integrating incident data from five reporting systems to assess patient safety: making sense of the elephant. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:402-410. 17.Moore IN, Pichert JW, Hickson GB, Federspiel C, Blackford JU. Rethinking peer review: detecting and addressing medical malpractice claims risk. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2006;59:1175-1206. 18. Mukherjee K, Pichert JW, Cornett MB, Yan G, Hickson GW, Diaz JJ Jr. All trauma surgeons are not created equal: asymmetric distribution of malpractice claims risk. J Trauma. 2010;69:549-554. 19.Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson ML. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118:1126-1133. 20. Stimson CJ, Pichert JW, Moore IN, et al. Medical malpractice claims risk in urology: an empirical analysis of patient complaint data. J Urol. 2010;183:1971-1976. 21. Guillamondegui OD, Gunter OL, Hines L, et al. Using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative to improve surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:709-714. 22.Hickson GB, Pichert JW, Federspiel CF, Clayton EW. Development of an early identification and response model of malpractice prevention. Law Contemp Probl. 1997;60(12):7-29. 23. Sloan FA, Mergenhagen PM, Burfield WB, Bovbjerg RR, Hassan M. Medical malpractice experience of physicians. Predictable or haphazard? JAMA. 1989;262:3291-3297. 24. Vincent C, Davis R. Patients and families as safety experts. CMAJ. 2012;184:15-16. 25. Fink AS, Campbell DA, Mentzer RM, et al. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-veterans administration hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Ann Surg. 2002;236:344-354. 26.Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Factbook 20132014. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/documents/main/files/ Factbook_2014_web_version.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2015. Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015 8 American Journal of Medical Quality 27.US News and World Report. , Vanderbilt University Medical Center. http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/ area/tn/vanderbilt-university-medical-center-6521060. Accessed April 1, 2015. 28. American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). User Guide for the 2011 Participant Use Data File. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012:3-6, 25-26, 33. 29. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, et al. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994;272:1583-1587. 30.Pichert JW, Hickson G, Moore I. Using patient com plaints to promote patient safety. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. 31. Pichert JW, Moore IN, Karrass J, et al. An intervention model that promotes accountability: peer messengers and patient/family complaints. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:435-446. 32.Murff HJ, France DJ, Blackford J, et al. Relationship between patient complaints and surgical complications. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:13-16. 33.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. 34. Felps W, Mitchell TR, Byington E. How, when, and why bad apples spoil the barrel: Negative group members and dysfunctional groups. In: Staw BM, ed. Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2006:175-222. 35. Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:520-526. 36. Reiter CE, Pichert JW, Hickson GB. Addressing behavior and performance issues that threaten quality and patient safety: what your attorneys want you to know. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:37-45. 37.Pichert J, Johns JA, Hickson GB. Professionalism in support of pediatric cardio-thoracic surgery: a case of a bright young surgeon. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32: 89-96. 38. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Miller CS, Pichert JW, Entman SS. Satisfaction with obstetric care: relation to neonatal intensive care. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:288-292. Downloaded from ajm.sagepub.com at VANDERBILT UNIV on May 24, 2015