Carryover and spillover effects of financial incentives in health: lab-field evidence

advertisement

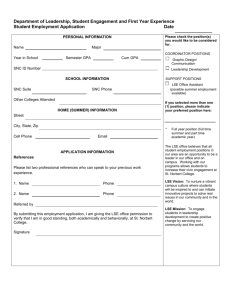

Carryover and spillover effects of financial incentives in health: lab-field evidence Matteo M Galizzi LSE Behavioural Research Lab LSE Health and Social Care Department of Social Policy Centre for the Study of Incentives in Health Paris School of Economics, Hospinnomics, J-PAL Europe UCL CBC Research Seminar, 13th May 2014 Acknowledgements Many thanks to CBC, Michelle Baddeley and Antonio Cabrales. Work within the Centre for the Study of Incentives in Health (CSIH) • Behavioural/health economists at LSE • Health psychologists at KCL • Bioethics/philosophy experts at QMUL All studies funded by the CSIH from a strategic award by the Wellcome Trust Biomedical Ethics Programme (086031/Z/08/Z). Many thanks to the Wellcome Trust and to CSIH people. Joint work with Paul Dolan (LSE) and Daniel Navarro-Martinez (UPF). Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Road map “Unintended behavioural consequences” of incentives in health • A frame and taxonomy of ‘behavioural spillovers’ • A study on ‘carryover’ effects • A study on ‘spillover’ effects Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Incentives in health A key interest to economists is how people react to incentives (Camerer & Hogarth, 1999; Laffont & Martimort, 2002; Gneezy & List, 2013) ‘Basic law of behaviour’ (Gneezy et al. 2011): higher incentives lead to greater effort and performance Incentives for healthy behaviours (Marteau et al. 2009; Volpp et al. 2011; Loewenstein et al. 2012) ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ Weight loss (Volpp et al., 2008; John et al. 2011, 2012; Kullgren et al. 2013) Smoking cessation (Volpp et al., 2006; 2009) Gym attendance (Charness & Gneezy, 2009) Consumption of fruit and veg (Cooke et al. 2011) Children immunization (Banerjee et al., 2009) Children health in schools (Vera-Hernandez et al., 2015) Incentives can change health behaviour in the short-run, when super-charged by ‘behavioural’ insights (Loewenstein et al. 2007) Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk ‘Hidden costs’ of incentives Mounting evidence on the ‘hidden costs’ of incentives (Fehr & List, 2004) Especially when high, incentives can Crowd out intrinsic motivation (Frey & Oberholzer-Gee) Change social norms or individual beliefs about social norms (Gneezy & Rustichini 2000a,b; Fehr & Falk, 2002; Heyman & Ariely, 2004) Interact with reciprocity (Fehr & Gachter, 1997; Rigdon, 2009; Dur et al. 2010), reputation (Benabou & Tirole, 2006; Ariely et al. 2009), and social comparison concerns (Gachter & Thoni, 2010; Greiner, Ockenfels, & Werner, 2011) Lead subjects to ‘choke under pressure’ because of anxiety or arousal (Ariely, Gneezy, Loewenstein & Mazar, 2009) Two relatively unexplored aspects of the ‘unintended consequences’ of (health) incentives… Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk ‘Unintended behavioural consequences’ of incentives Carryover Once they are removed, incentives can have ‘carryover’ effects on the same targeted behaviour over time. Incentives cannot be in place forever… Same behaviour over time: today, tomorrow Spillover Incentives can have ‘spillover’ effects on health behaviours other than the ones directly targeted. Research and policy motivation Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk ‘Behavioural spillovers’ of incentives Spillovers on other behaviours Incentives can have ‘spillover’ effects on health behaviours other than the ones directly targeted. Sequence of two different behaviours: ¡ behaviour 1, behaviour 2 Linked, at conscious or unconscious level, by a ‘motive’ After all, no behaviour sits in a vacuum ¡ And we should capture all ‘ripples’ in the pond (Dolan & Galizzi, 2015a)… Promoting, permitting, purging spillovers ¡ ¡ Dolan & Galizzi (2015a) Contrast/assimilation (Cialdini et al. 1995), highlight/balance (Dhar & Simonson, 1999; Fishbach et al. 2013)… Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Behavioural spillovers Second behaviour A run after work First behavior Eat healthily Eat less healthily 1. Promoting 2. Permitting I ran an hour, let’s keep up the good work I ran an hour, I deserve a big slice of cake Sofa-sitting after work 3. Purging 4. Promoting I’ve been lazy today, best not eat so much tonight I’ve been lazy today, so, what the heck, let’s have a big slice of cake Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Promoting spillovers in health Preference for consistency (Muller, Dijksterhuis et al. 2009) If you write down as many arguments you can of why smoking is bad, once outside the lab, you wait significantly longer before you smoke a cigarette Survey effects (Zwane et al., 2011) Survey HHs either biweekly (18 times) or every 3 months (3 times) ¡ Some questions on health status and behaviours ¡ 18 months after, Kenya’s HHs surveyed more often had higher chlorine in the stored drinking water ¡ Borrowers from a rural bank in Philippines… ¡ 9 months later were 25% more likely to take up government sponsored health insurance sold door to door Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Permitting spillovers in health (I) Licensing • Subjects with healthy options as default were more likely to order healthy sandwiches but then have more side dishes/drinks/ desserts: (Wisdom et al., 2010) • Subjects who had healthy main dishes more likely to have side dishes/drinks/desserts: (Chandon & Wansink, 2007) • Subjects asked to read a scenario there they walked 30 minutes: then serve +51.8-59.8% more snacks than reading a neutral scenario (Werle et al., 2010) • Subjects given placebo pills and said they were either multivitamins supplements or placebo: subjects told they were multivitamins then expressed higher preferences for unhealthy activities and walked less to return a pedometer than subjects told they were placebo (Chiou et al., 2010, 2011) Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Permitting spillovers in health (II) Ego depletion (Baumeister et al., 1998) After exerting high levels of physical or cognitive self-control in behaviour 1, in behaviour 2 you exert lower levels self control ¡ Two bowls in front of you: hot cookies and radishes. ¡ You are told to taste only the radishes, for 5 minutes. ¡ The experimenter leaves for 5 minutes ¡ Back with a puzzle, in fact impossible to solve. ¡ After having resisted the temptation of indulging in cookies you quit sooner on trying to solve the puzzle To exert self-control we draw from a limited pool of mental energy Physical and mental effort consumes energy: blood glucose drops ¡ If after task 1 you drink a sweet milkshake, you performed better in another effortful task 2! (Gaillot, Baumeister et al., 2007) Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk ‘All negative’ promoting spillovers in health What-the-hell effect (Policy & Herman, 1985; Wilcox et al., 2009) Once you decide upon a course of actions that is inconsistent with a goal/motive… and thus abandon goal–directed behaviour (behaviour 1), then… Instead of taking the middle ground, you are... More likely to exacerbate extent of your failure to behave in line with the goal (behaviour 2) ¡ Once you abandon the diet to eat a cookie, instead of selecting a low-fat cookie you eat the most unhealthy/whole bag of cookies Abstinence violation effects Similar effects have been documented among alcoholics (Collins & Lapp, 1991), smokers (Shiffman, Hickcox, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Richards, 1996), and drug users (Stephens & Curtin, 1994). Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Do ‘spillovers’ also occur with incentives? Spillovers are everywhere, and health is not an exception Most evidence on behavioural spillovers has been documented in absence of financial incentives over time. Traditional experimental economics view: Most of these ‘behavioural anomalies’ disappear when real money is on the table Do incentives in health also have carryover/spillover effects? Two exploratory lab-field experiments Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Carryover effects Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Dolan, Galizzi, Navarro-Martinez (2015) in 30’’… Randomised controlled ‘nested’ lab experiment to explore: “Carryover” effects of financial incentives over time On the same target health behaviour: sweets eating Compare incentives ‘to eat’ versus ‘not to eat’ Incentives ‘not to eat’ have stronger carryover effects 2 days later Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Key questions Do incentives have ‘carryover’ effects once they are removed? First experiment to compare head-to-head monetary incentives ‘to act’ or ‘to abstain to act’ Consider ‘ambivalent’ health activity: sweets eating Example of pleasurable behaviour, that is potentially harmful (and unwanted at a deeper level) Which incentives have stronger carryover effects? Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Subjects’ pool and experimental set up Research ethics: protocol approved ¡ ¡ LSE REC CSIH Behavioural Research Lab ¡ ¡ ¡ Cross-departments lab at LSE 1 “proper” lab + 6 small rooms Experiments run between end of June and September 2012 Invitation to BRL mailing list (about 5,000 subjects) ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ Under- and post-graduate students Staff members, alumni working in London area Mailing list managed by SONA system software Subjects identified by SONA ID code Payment was £30, if they participated to 3 sessions in a week ¡ ¡ ¡ Monday, Wednesday, Friday 35 sessions run, 5 sessions a day 10 am, 11.30 am, 1 pm, 2.30 pm, 4 pm Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Randomisation and overall structure Arrived to BRL, read and sign informed consent form ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ A total of 353 subjects participated Anonymously identified by their SONA ID code Use SONA ID code to link observations across days Asked to pick a number to be assigned to their cubicle in the lab Random cubicle assigned to one of 3 groups: Eat, Don’t Eat, Control. Enter the main room in the lab and given written instructions Session 1 (Monday): a questionnaire, 3 videos: 1, 2, 3 ¡ In video 2 the experimental manipulation: incentives Session 2 (Wednesday): ‘filler’ task (completely unrelated), then 1 video: 4 Session 3 (Friday): a control questionnaire (other tasks) ¡ Big 5 Inventory, Health & Taste Attitudes, sweets intakes, BMI, diet Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Key design features Subjects in LSE BRL watched different videos on computer screens… ¡ ¡ A total of 4 videos during two sessions set 2 days apart (Monday, Wednesday) Mildly boring 10’ videos: bus journey in London, animals documentaries, video 2 was 5’ about sweets-making (cover story) Leave bowls of sweets next to participants: ¡ Jelly Beans: 2.2 Kcal, 1.14 gr per Jelly Bean… Sweet eating monitored throughout all videos: ¡ ¡ After each video subjects moved to a different room allegedly to answer a questionnaire on the videos Meanwhile, bowls of sweets were weighted with high-precision scales… Monetary incentives introduced in a video in first session Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Videos and treatments 3 videos in session 1, 1 in session 2 Video 1: ‘could eat as they like’: baseline ‘preference’ for sweets eating Video 2: incentive manipulation (depends on group) Video 3: incentives are removed, could keep eating as they like: first indicator of carryover Video 4: could eat as they like, cleaner indicator for carryover effects Randomly allocate subjects to Eat (n=133): get £3 if would eat at least 10 Jelly Beans Don’t Eat (n=112): get £3 if would do not eat any Jelly Bean Control (n=108): could eat as they like Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Summary of treatments Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Main results Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Summary of main results Randomization worked, no sample bias: ¡ No significant differences in sweet-eating across conditions in Video 1. Financial incentives worked, as expected: Video 2. Subjects in Don’t Eat condition ate less sweets in Video 3, despite having eaten less in Video 2: carryover effects. Subjects in Don’t Eat condition ate less sweets also in Video 4, two days later! Clear carryover effects. Significant difference between sweets eaten in Videos 4 and 1. Regression analysis confirms significant effect of Don’t Eat condition ¡ In general, subjects more anxious, with higher BMI, and who usually eat more sweets, also ate more Jelly Beans Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Conclusions and limitations First study to compare head-to-head incentives ‘to act’ versus ‘to abstain to act’ in the same health context/environment An ambivalent health behaviour: incentives ‘to eat’ vs ‘not to eat’ Both incentives were effective in changing target behaviour Incentives ‘not to eat’ also had significant carryover effects Carryover effects persisted until 2 days after incentives were removed Consistent with the ‘bad is stronger than good’ effect in psychology (Baumeister et al., 2001): ¡ Negative messages are easier to retain than positive ones. Limitations make difficult to generalise results: students, 2 days… Potentially extendable to other ‘ambivalent’ behaviours ¡ Drinking, unsafe sex, reckless driving? Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Spillover effects Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Dolan and Galizzi (2015b) in 30’’… Conduct a randomised controlled ‘lab-field’ experiment to explore “unintended spillovers” of incentives in health Consider incentives for real-effort physical task High financial incentives can “spillover” on eating behaviour Key driver seems to be level of satisfaction with the task Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Key questions Incentives are usually effective in changing target behaviour. Can incentives also have spillovers? No RCTs evidence on long-term spillovers (Mantzari et al. 2014) An exploratory lab-field experiment focusing on short-term effects 3 questions: 1. Whether spillovers occur when real money is on the table 2. Whether they depend on the size (high versus low) and nature (financial versus non-financial) of the incentives 3. Which behavioural mechanisms are most likely to ‘drive’ the spillover effects Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Key design features Spillovers relevant for both research and policy purposes Stylised incentives for physical activity: ‘calories out’ ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ Della Vigna & Malmendier (2006), Acland & Levy (2013), Cawley et al. (2013) Incentives are effective: Charness & Gneezy (2009) We directly observe outcomes Stepping for 2 minutes Non-targeted behaviour where spillovers can occur is healthy eating: ‘calories in’ ¡ ¡ ¡ As in Subway experiment by Wisdom et al. (2010) Werle et al. (2010), Van Kleef et al. (2011), Chiou et al. (2011a) Choice of food for lunch Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Key design features (II) Randomly allocate subjects to ¡ either treatment incentives groups (H, L, E) or control group (C) Spillovers if eating in H, L, E significantly different than C Both types of spillovers are possible in principle: Promoting spillovers: lower ‘calories in’ than C ¡ Priming: healthy stepping leads to healthy eating (Muller et al. 2010) Permitting: higher ‘calories in’ than C Licensing: rewards give sense of ‘deservingness’ that ‘licenses’ indulging more in tastier, but also more energy-dense, food ¡ (Ego depletion: having exercised harder under incentives’ strain, subjects felt more ‘depleted’ in their physical/mental energy: glucose) Disentangle drivers of permitting spillovers ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Subjects’ pool and experimental set up Research ethics: protocol approved ¡ ¡ LSE REC CSIH Behavioural Research Lab ¡ ¡ ¡ Cross-departments lab at LSE 1 “proper” lab + 6 small rooms Experiments run between end of April and September 2012 Invitation to BRL mailing list (about 5,000 subjects) ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ Under- and post-graduate students Staff members, alumni working in London area Mailing list managed by SONA system software Subjects identified by SONA ID code Payment was £10, possibly plus amount depending on tasks ¡ ¡ ¡ 156 subjects 24 sessions run, 5 sessions a day 11 am, noon, 1 pm, 2 pm, 3 pm Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Randomisation and Task A Arrived to BRL, read and sign informed consent form ¡ ¡ ¡ ¡ Anonymously identified by their SONA ID code Asked to pick a number to be assigned to their cubicle in the lab Random draw of cubicle assigned them to either C (n=38) or one of 3 treatment groups H (n=40), L (n=39), E (n=39) Enter the main room in the lab and given written instructions Going to participate into 3 tasks: A, B, C ¡ Tasks A and C questionnaires, B simple physical task, to be explained Task A ‘filler’ questionnaire, identical for all groups ¡ ¡ Subjective perception of time, light, temperature, hunger... using 0-180 mm slider scales While doing Task A, subjects approached individually to do Task B Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Task B Subjects move individually to other room in the BRL Height and weight are measured on scale (no shoes) ¡ Professional heart rate meter: heart rate measured (bpm) ¡ Questions on life satisfaction: 0-10 Likert scale (Dolan et al. 2011) ¡ ÷ Including question on ‘how happy’/ ‘how full of energy’ they feel Room has a gym stepper ¡ Invited to step “as many times as they can in 2 minutes”: ¡ ÷ Stepping up and down with both feet on the stepper ÷ Experimenter shows how to do it Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk A note on stepping Stepping for 2 minutes Picked for several reasons ¡ Very simple and familiar physical task ¡ Moderate physical task with no major physiological effect ÷ Stepping ¡ 2’ at quiet pace (about 60 steps) is climbing up 4 floors Amount of calories burnt is minimal: ÷ Depending ¡ on HR, gender, age, and weight about 15-25 Kcal Ethics approval Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Experimental treatments • In all groups experimenter keeps time and counts steps • C: at the end of Task B, subjects draw a number ¡ ¡ If the same number randomly drawn at the end of the experiment They get an extra-payment of £20 H: end of session, paid 10p per step they do in 2 minutes L: paid 2p per step they do in 2 minutes E: ‘nudged’ to work hard through verbal encouragement ¡ ¡ ¡ No money at all Every 20 seconds verbal encouragements ‘well done, keep going, you’re doing really well, only another 40 seconds to go...’ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Immediately after Task B Immediately after subjects finished stepping Experimenter take again heart rate measure ¡ Asked how satisfied with just accomplished task: 0-10 scale ¡ Questions on life satisfaction, e.g. ‘how full of energy’: 0-10 scale ¡ Told number of steps and payments, and draw number f0r C ¡ Experimenter say to take a rest before going back to Task A\C ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk ‘Obfuscation’ RA bring subjects to one of 2 other small rooms Rooms were prepared ostensibly for subjects to take a rest ¡ Room has chairs and a table ¡ Told to relax for as long as they like ¡ On table, various foods and drinks were arranged ¡ Could help themselves with whatever drink or food they like ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Resting between tasks... Same foods and drinks in C and T groups and for subjects Every subject finds exactly same types and quantities of foods/ drinks ¡ Arranged in the same order and presentation ¡ Unbeknownst to subjects, number and type of food or drink item consumed in the lunch was recorded... ¡ When a subject leaves the room to go back to Task A... ¡ Foods & drinks consumed are registered and replaced for next ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Food and drink items Foods & drinks selected To guarantee that all subjects have their own “cup of tea” ¡ All food from a leading UK supermarket ¡ On each item nutritional label upfront: “pie” + “traffic lights” ¡ Also, a full GDA nutritional label in the back of item ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk The menu... Foods & drinks selected Drinks: water, coke, orange juice ¡ 3 “full fat” sandwiches: BLT, chicken & bacon, ham & cheese ¡ 3 “low fat” sandwiches (<3% fat): chicken salad, tuna & cucumber, chicken & bacon “light” (Be Good To Yourself) ¡ 3 vegetarian sandwiches: cheese & tomato, hummous & carrots, cheese & celery ¡ Sweets: Apples, brownie bites, chocolate & cornflakes bites, strawberries and chocolate muffins ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Menu unpacked... KCal Fats Sat Fats Sugars Salt BLT 407 16.7 3.5 5 1.99 Ham & Cheese 456 15.6 3.4 5.3 2.11 Chicken Triple 509 16.8 2.8 4.1 2.04 Roast Chicken Salad (BGtY) 273 3.8 0.7 2.9 0.95 Chicken & Bacon (BGtY) 333 6 1.9 3.3 1.54 Tuna & cucumber (BGtY) 283 4.9 0.8 4 1.12 Cheese & Tomato (V) 401 19,6 12,7 2,9 1,74 Cheese & celery (V) 438 22,9 10,7 3,5 1,53 Hummous & carrots (V) 321 6,1 1,4 3,5 1,44 Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Back to Task A, Task C After lunch, subjects go back to complete questionnaire in Task A ¡ After finishing Task A, subjects also go through Task C ¡ Brief control questionnaire on ¡ ÷ when is the last time they have eaten before coming to the lab ÷ what they have eaten ÷ what they have had for breakfast, lunch and dinner the day before ÷ physical activities they had last 24 hours... Also, questionnaire asks how many calories they think to have burnt in the physical exercise task ¡ And how many calories they think to have eaten in the lunch ¡ How much satisfied they felt with their performance in task B ¡ Payment phase takes place for all subjects ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Constructing variables and indexes Number of performed steps: Steps Difference in Heart rate before and after steps: DiffHR (bpm) ¡ Feeling ‘full of energy’ before and after steps: DiffEnergy (0-10) ¡ Satisfaction with task immediately after: ImSatisf (0-10) ¡ And at the end of experiment: EndSatisf (0-10) Number of Kcal consumed in lunch in total: KcalIn Types of foods: KcalSandw, KcalCrisps, KcalSweets, KcalDrinks ¡ Nutritional intakes: Fats, SatFats, Sugars, Salt ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Calculating Kcal Out State-of-art physiology models fitted by Keytel et al. (2005) Behind most popular software, apps, and online calculators. Two variants: ¡ A measure for maximal oxygen consumption measure (VO2max) is available ÷ ¡ Subjects need to breath into a mask during exercise VO2max is not available When no VO2max, estimated KcalOut are functions of: ¡ Gender ¡ Age ¡ Weight ¡ Duration of physical exercise ¡ Heart rate (immediately after task) Gender-specific models for KcalOut: • Male subjects KcalOut = [-55.0969 + 0.630 * Heart Rate (in bpm) – 0.1988 * Weight (in Kg) + 0.2017 * Age (in Years)] * Time (in minutes) / 4.184 • Female subjects KcalOut = [-20.4022 + 0.4472 * Heart Rate (in bpm) – 0.1263 * Weight (in Kg) + 0.074 * Age (in years)] * Time (in minutes) / 4.184 Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Variables, again Excess calories Extent to which, in meal, subjects ‘replenished’ the calories spent in physical task ¡ ¡ Individually-calculated balance between ‘calories in’ and ‘calories out’: ExcessKcal = KcalIn - KcalOut Other variables are standard: ¡ ¡ Dummy for female Female Dummies for treatment groups: TreatH, TreatL, TreatE Self-reported level of hunger from Task A: Hunger (0-180) ¡ Self-reported time from last meal from Task C: LastEat (minutes) Subjective estimates of number of Kcal ¡ ¡ Burnt in stepping: EstKcalOut Consumed in lunch: EstKcalIn Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Age Female Weight Weekly Rent Expense SAH HR Before Happy Hunger Observations H L E C Total 25.62 26.51 25.12 24.63 25.47 (5.69) (6.53) (7.87) (4.72) (6.28) 0.60 0.65 0.67 0.71 0.65 (0.49) (0.48) (0.47) (0.46) (0.47) 63.4 65.32 63.14 63.21 63.77 (12.44) (15.87) (11.29) (13.88) (13.37) 175.81 158.21 173.61 160.73 167.23 (133.76) (131.51) (149.71) (98.61) (128.47) 3.6 3.62 3.59 3.71 3.62 (0.87) (0.92) (0.82) (0.65) (0.81) 82.67* 78.05 75.80 77.16 78.52 (12.95) (16.42) (10.43) (14.21) (13.78) 7.10 7.14 6.97 7.21 7.11 (1.69) (1.31) (1.58) (1.71) (1.57) 48.17 62.05 52.77 49.39 52.97 (39.41) (35.27) (35.24) (33.11) (35.94) 40 39 39 38 156 Steps DiffHR DiffEnergy ImmSatisf EndSatisf KcalIn KcalOut ExcessKcal Observations H 102.5*** L 105.5*** E 92.49 C 89.42 Total 97.58 (13.35) (19.15) (18.55) (16.91) (18.24) 64.4** 68.67** 63.39* 51.66 61.95 (22.93) (28.66) (25.25) (27.18) (26.53) 0.225 1.128** 0.243 -0.132 0.368 (1.746) (2.105) (1.716) (2.462) (2.059) 8.42*** 7.064* 7.487*** 6.394 7.355 (1.059) (1.857) (1.519) (1.701) (1.712) 7.9*** 6.807** 7.128*** 6.039 6.981 (1.516) (1.768) (1.417) (1.817) (1.753) 433*** 319.23* 350.12* 233.04 335.10 (297.81) (283.49) (286.4) (306.3) (299.44) 16.95** 16.61** 15.402 13.27 15.58 (5.817) (6.424) (6.279) (7.385) (6.587) 415.9*** 302.62 334.72* 219.77 319.52 (299.69) (284.07) (286.23) (305.34) (299.5) 40 39 39 38 156 Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk KcalSandw KcalCrisps KcalSweets KcalDrinks Fats SatFats Sugars Salt Observations H L E C Total 169.52 155.49 173.15 143.83 160.66 (222.02) (186.69) (198.35) (230.35) (208.31) 79.2*** 20.31 25.38 13.89 35.11 (77.94) (45.81) (51.60) (41.05) (61.56) 97.72* 95.54 109.67 38.32 85.69 (131.72) (153.33) (156.08) (87.47) (136.69) 86.45*** 47.89 41.92 37.00 53.63 (54.25) (71.37) (55.35) (62.74) (63.78) 14.80*** 9.08** 11.23* 6.431 10.440 (11.39) (9.449) (9.834) (10.353) (10.646) 3.932*** 2.91** 3.401*** 2.016 3.078 (4.517) (3.448) (3.493) (4.206) (3.970) 31.52*** 23.60* 22.39 14.40 23.09 (17.02) (25.91) (22.79) (19.48) (22.19) 0.843** 0.654 0.754 0.595 0.713 (0.934) (0.754) (0.809) (0.954) (0.864) 40 39 39 38 156 Second look at the data Significant differences in ExcessKcal across treatments are due to two, conceptually distinct, factors How many subjects choose to have lunch % KcalIn>0 Observations H 90.00** 40 L 84.62* 39 E 76.92 39 C 71.05 38 How much to eat/drink given choice to have lunch # KcalIn|KcalIn>0 Observations H 481*** L 377.28 E 455** C 327.98 (273.91) (269.92) (240.95) (318.03) 40 39 39 38 Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Modelling two decisions Two-part (hurdle) model ¡ Two decisions are generated by potentially different underlying mechanisms: simple and flexible First part: choose whether or not to have lunch Binary choice probit model ¡ Dependent variable: =1 if KcalIn>0, =0 otherwise ¡ Second part: how many excess calories to consume, given the option to have lunch Linear regression model, in logs, with heteroskedastic-robust SE ¡ Dependent variable: E (Ln Excess Kcal | KcalIn>0 ) ¡ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Pr(KcalIn)>0 TreatH m1 0.727** (0.345) TreatL 0.465 (0.325) TreatE 0.181 (0.309) Female Hunger LastEat Steps DiffEnergy DiffHR Constant 0.555*** (0.215) Obs Pseudo R2 156 0.0352 Pr(KcalIn)>0 TreatH TreatL TreatE m1 0.727** m2 0.693** m3 0.768** m4 0.792** (0.345) (0.349) (0.358) (0.364) 0.465 0.548 0.473 0.458 (0.325) (0.342) (0.351) (0.356) 0.181 0.157 0.155 0.270 (0.309) (0.311) (0.318) (0.330) -0.447 -0.340 -0.469 (0.273) (0.282) (0.298) 0.0096** 0.0116*** (0.0038) (0.0041) Female Hunger LastEat -0.00029 (0.00058) Steps DiffEnergy DiffHR Constant Obs Pseudo R2 0.555*** 0.885*** 0.359 0.414 (0.215) (0.299) (0.362) (0.377) 156 0.0352 154 0.0579 154 0.104 152 0.124 Pr(KcalIn)>0 TreatH TreatL TreatE m1 0.727** m2 0.693** m3 0.768** m4 0.792** m5 0.792** m6 0.788** m7 0.747** (0.345) (0.349) (0.358) (0.364) (0.377) (0.363) (0.368) 0.465 0.548 0.473 0.458 0.458 0.497 0.360 (0.325) (0.342) (0.351) (0.356) (0.372) (0.362) (0.365) 0.181 0.157 0.155 0.270 0.270 0.279 0.271 (0.309) (0.311) (0.318) (0.330) (0.331) (0.331) (0.341) -0.447 -0.340 -0.469 -0.469 -0.505* -0.463 (0.273) (0.282) (0.298) (0.298) (0.304) (0.300) 0.0096** 0.0116*** 0.0116*** 0.0117*** 0.0106** (0.0038) (0.0041) (0.0042) (0.0041) (0.0042) -0.00029 -0.00029 -0.00030 -0.00026 (0.00058) (0.00058) (0.00058) (0.00059) Female Hunger LastEat Steps -0.00001 (0.00750) DiffEnergy -0.0405 (0.0625) DiffHR 0.00340 (0.00514) Constant Obs Pseudo R2 0.555*** 0.885*** 0.359 0.414 0.415 0.436 0.276 (0.215) (0.299) (0.362) (0.377) (0.775) (0.380) (0.446) 156 0.0352 154 0.0579 154 0.104 152 0.124 152 0.124 152 0.127 146 0.116 Ln(ExcessKcal) TreatH m12 0.599** (0.257) TreatL 0.305 (0.261) TreatE 0.625** (0.246) Female Hunger LastEat Constant 5.27*** (0.207) Obs 126 R2 0.0695 Adj R2 0.0467 Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Ln(ExcessKcal) TreatH TreatL TreatE m12 m13 m14 m14 m16 0.599** 0.568** 0.596** 0.568** 0.593** (0.257) (0.259) (0.254) (0.260) (0.255) 0.305 0.281 0.244 0.246 0.220 (0.261) (0.265) (0.272) (0.265) (0.271) 0.625** 0.625** 0.614** 0.625** 0.614** (0.246) (0.245) (0.249) (0.246) (0.251) -0.365** -0.313* -0.373** -0.331** (0.164) (0.172) (0.158) (0.165) Female Hunger 0.00399 0.00388 (0.0025) (0.0027) LastEat Constant 0.00006 -0.00006 (0.0005) (0.0005) 5.27*** 5.51*** 5.25*** 5.5*** 5.28*** (0.207) (0.242) (0.277) (0.253) (0.271) 126 125 125 124 124 R2 0.0695 0.105 0.127 0.110 0.130 Adj R2 0.0467 0.0751 0.0903 0.0720 0.0849 Obs Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Ln(ExcessKcal) TreatH m17 0.596** (0.254) TreatL 0.244 (0.272) TreatE 0.614** (0.249) Female -0.313* (0.172) Hunger 0.0039 (0.0025) Steps DiffEnergy DiffHR Constant 5.25*** (0.277) Obs R2 Adj R2 125 0.127 0.0903 Ln(ExcessKcal) TreatH TreatL TreatE Female Hunger m17 0.596** m18 0.635** m19 0.636** m20 0.613** m21 0.661** m22 0.650** m23 0.634** (0.254) (0.265) (0.256) (0.253) (0.266) (0.255) (0.264) 0.244 0.295 0.305 0.296 0.337 0.357 0.326 (0.272) (0.299) (0.278) (0.287) (0.300) (0.291) (0.308) 0.614** 0.620** 0.650** 0.642** 0.651** 0.678** 0.638** (0.249) (0.254) (0.255) (0.263) (0.257) (0.265) (0.263) -0.313* -0.323* -0.346** -0.312* (0.172) (0.171) (0.168) (0.178) (0.169) (0.174) (0.177) 0.0039 0.004 0.0043* 0.00405 0.0043* 0.0043 0.0039 (0.0025) (0.0025) (0.0025) (0.0027) (0.0025) (0.0026) (0.0027) Steps -0.0022 -0.0025 (0.0051) (0.0052) (0.006) -0.0374 -0.0333 -0.0386 (0.0439) (0.0453) (0.0453) DiffHR Obs R2 Adj R2 -0.321* -0.0029 DiffEnergy Constant -0.350** -0.349** -0.0011 -0.001 -0.0003 (0.0035) (0.0035) (0.004) 5.25*** 5.52*** 5.23*** 5.31*** 5.44*** 5.28*** 5.50*** (0.277) (0.489) (0.277) (0.312) (0.510) (0.317) (0.514) 125 0.127 0.0903 125 0.130 0.0856 125 0.132 0.0881 120 0.123 0.0763 125 0.134 0.0821 120 0.128 0.0740 120 0.125 0.0698 Alternative models/robustness checks Results are robust to broad set of alternative specifications: Using ExcessKcal in levels Focusing analysis on subsample where few dummies were ‘trimmed’ off: ¡ 3 subjects consumed more than 1,000 Kcal, 1 each for H, L, and C Using KcalIn in levels or logs in the second step Using as dependent variable ¡ ¡ Either the number of calories in each food category (e.g. KcalSandw, KcalCrisps) Or more refined nutritional intakes (e.g. fats, sugars) Using discrete choice models for the likelihood to consume ‘healthy’ versus ‘energy-dense’ food and drink items General message: more satisfied subjects, i.e. in H, tended to have more: (excess) calories, intakes of fats/sugars, energy dense items Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Discussion: spillovers In H and E (but not L) 200 more excess Kcal than C ¡ ¡ A can of coke: 143 Kcal; pack of crisps: 112 Kcal About 25 minutes stepping... More excess calories rule out any ‘promoting’ spillovers: ¡ ¡ Consistent with Thogersen and Crompton (2009), Evans et al. (2013): Incentives decrease likelihood of ‘promoting spillovers’ in environmental behaviours Left with ‘permitting’ spillovers. Which one? ¡ ¡ ¡ Licensing (Ego-depletion) (Take-the-most-out-of-it) Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Discussion: Licensing Most plausible explanation H manifested higher levels of satisfaction with the task ¡ Higher sense of ‘deservingness’ Higher satisfied subjects tend to eat more excess calories in lunch Excess calories mainly took form of tasty and self-indulging energy-dense side dishes: ¡ ¡ Sweetened drinks Crisps Crisps hard to explain with ‘glucose’ repletion Go along well with ‘licensing’: feeling entitled to treat myself ¡ Feel I’m ‘worth it’ Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Conclusions and limitations Major limitation: a sample of students ¡ Instead of subjects who suffer from actual health problems related to risky behaviour (e.g. overeating). Need more confirmations, but main finding that… High (but not low) financial incentives have ‘licensing’ spillovers Have number of practical implications: Research methodology: caution is due when interpreting results of experiments involving sequences of tasks, in particular ¡ ¡ Incentivised (e.g. games, eliciting preferences) and Non-incentivised tasks (e.g. questionnaires, field) Policy: in health contexts, modest financial incentives can work as well as large financial rewards, while ¡ ¡ Being more cost-effective Presenting lower risks of unintended spillovers Matteo M Galizzi, LSE: m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Thank you very much m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk Thank you very much m.m.galizzi@lse.ac.uk • Dolan P, Galizzi MM. Like Ripples on a Pond: Behavioural Spillovers and Their Consequences for Research and Policy, Journal of Economic Psychology, 2015, 47, 1-15. • Dolan P, Galizzi MM, Navarro-Martinez D. Paying People to Eat or Not to Eat? Carryover Effects of Monetary Incentives on Eating Behaviour, Social Science and Medicine, 2015, 133, 153-158. • Dolan P, Galizzi MM. Because I’m Worth it: a Lab-Field Experiment on Spillover Effects of Incentives in Health, LSE CEP Discussion Paper CEPDP1286.