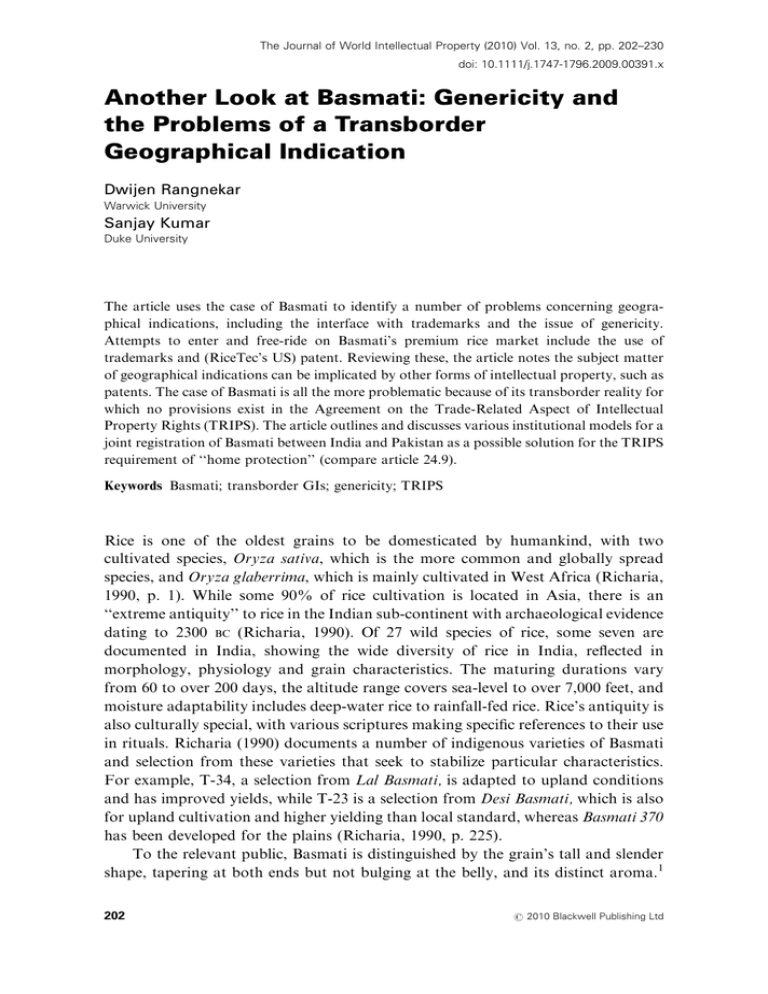

The Journal of World Intellectual Property (2010) Vol. 13, no.... doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1796.2009.00391.x

advertisement