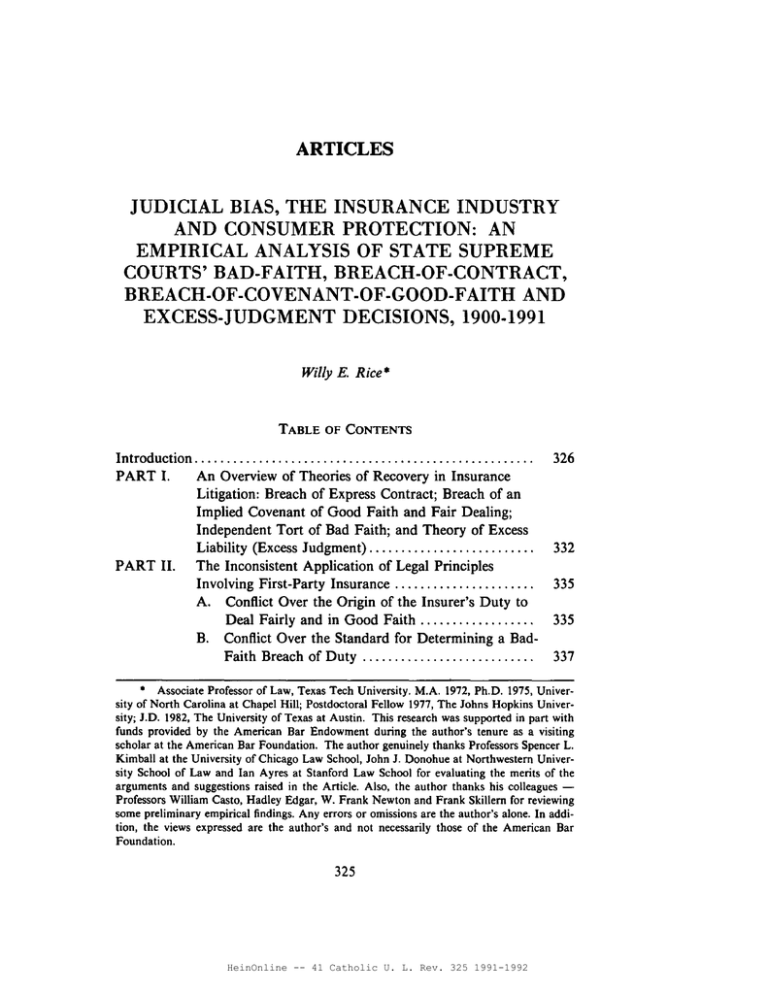

JUDICIAL BIAS, THE INSURANCE INDUSTRY AND CONSUMER PROTECTION: AN COURTS' BAD.FAITH, BREACH·OF·CONTRACT,

advertisement