Genetic When Public Health and Privacy

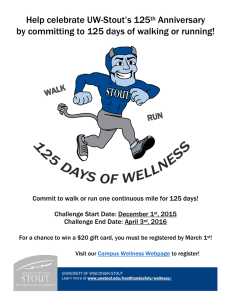

advertisement