1 L E G A L E T H I... W I L L I A M G A...

advertisement

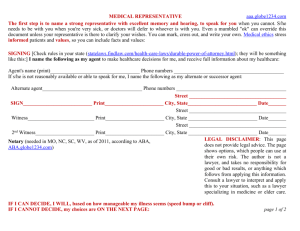

LEGAL ETHICS WILLIAM GARRY 1 PROBLEM BAKER PROBLEM 16 NOTE: For the sake of writing a more formal opinion, I have change the designation of the lawyer from the second to the third person, giving him the name Larry lawyer. Iarrimore Lawyer was at a dinner party on Saturday night and another of the guests learned that he was a lawyer. She asked him a "hypothetical problem" about a "friend of hers." After listening to her story, he said, "That person should see a lawyer." She replied, "When can I make an appointment?" He said, "How about next Thursday?" The next day, Larry was asked by his church to conduct a session on estate planning for wealthy members of churches of that denomination in the community. That evening, he spoke for approximately one hour on the benefits of giving appreciated stock, making inter-vivos gifts with a retained life estate, and so on. After his talk, a listener came up to him and said, "You know your stuff. I'd like for you to be my lawyer." On Monday, morning, Larry implemented a routine procedure In his office whereby five years after he had drafted a will for someone, he sent out a personal letter saying, "Most people find that their assets and family situation have changed sufficiently in five years that they ought to think about having changes made in their will. Why don't you stop In soon and have a routine legal check-up? It will put your mind at ease." 2 OPINION Three separate but related issues are discernable from the foregoing facts, each with its ancillary considerations: I. What ought Larry's reactions be, as a responsible attorney, to the guest's submission to him of the "hypothetical problem" concerning a "friend of hers" and her subsequent request for a personal appointment with respect to the same problem? Specifically, was his response, "How about next Thursday?" a proper one? In this regard, was his advice, "That person should see a lawyer," A. "volunteered" or B. "ill-motivated", so as to disqualify him from her? II. employment by May larry properly accept employment by the church member who had just listened to his lecture on estate planning? With respect to this second issue: A. What limitations are providing services to pitfalls include: placed on him and the church in the congregation? Potential (i) any use of larryJs name or the names of any of his partners or associates; (ii) any potential for self-laudation; and '(iii) any predetermined purpose of such a gathering to render individualized legal services, rather than educate the public in legal matters. III. Is the regular practice of sending out letters to clients, whose wills Larry has drafted, recommending that they have a routine legal check-up a proper one? What about: A. the clients' interests; and B. this practice with old or regular clients as opposed to new or potential clients? All three issues fall within.the parameters of Camion 2 of the American Bar Association Code of Professional Responsibility. It reads: A lawyer Should Assist the Legal Profession in Fulfilling Its Duty to Make Legal Counsel Available."1 O The Code thus recognizes an affirmative profession to provide obligation of the legal 2 access to the legal system. however, the limitations on solicitation of clients appears in the Disciplinary Rules under that same Can.1 on. entailed Oddly enough, Pertinent to all Issues herein is DR 2-104., which reads in its relevant portion: "A lawyer who has given unsolicited advice to a layman that he should obtain counsel or take legal action shall not accept employ's ment resulting from that advice. . .. Balanced somewhere on the horns of this delimma, we will embark on the examination of each of the issues before us, in the expectation that the Ethical Considerations found In the ABA CPR and other sources of authority will enlighten us on the proper course of (RE: EC 2-3 says: professional conduct. I. "Hypothetical Problem at dinner party) "Whether a lawyer acts properly In volunteering advice to a layman to seek legal services depends upon the circumstances. The giving of advice that one should take legal action could well be in fulfillment of the duty of the legal profession to assist laymen in recognizing legal problems. . .." (Emphasis a d d e d . T h e foremost question raised by Larry Lawyer's advice to reatin an attorney is whether such advice was "volunteered," as that term Is used by the ABA, and further, actively seeks it. arhn'r-P PAN "he "vnlnnt.eprpH" when the layman "The Cannons of Professional Ethics of the American Bar Association and the decisions of the courts quite generally prohibit the direct solicitation of business for gain by an attorney either through advertisement or personal communication; and also condemn the procuring of business by indirection through touters of any kind.Similarly, the American Bar Association Cannons of Professional Ethics, CanrOn 28, provides, in essence, that it is 4 disreputable for an attorney to breed litigation those who by seeking out have claims in order to secure them as clients, or to employ agents or runners, or to reward those who bring or influence the bringing of business to 7 such conduct. his law office.^ DR 2-130 adds: ment as a private practitioner And DR 2-103 B & C proscribe "A lawyer shll not recommend employof himself, hisgpartner, or associate to a non-lawyer who has not sought his advice." All of these imply that there is some element of affirmative action and even initiation of the intercourse between a lawyer and a layman in the "volunteering" of services or advice. advice. Also, involved is the motivation for giving such " . . . the advice is improper if motivated by a desire to g obtain personal benefit . . ..' Hence, we may conclude that the "volunteering" of services is the active solicitation of employment motivated by personal gain. It is dubious that such was the case here. First of all, the guest phrased her question deceptively, so as to give the impression that the problem was that of one of her friends. particularly There Is nothing odd about one friend asking another friend to "feel out" his or her legal position, especially if he or she. knew that such other friend would be seeing an attorney on a social basis. Perhaps intuition should have told larry that the problem might actually be that of been: the asking guest, in which case a proper inquiry would have "Is this 5T0UR problem?" But to chastise a lawyer for his lack of intuitive abilities seems frivilous and unproductive. The guest, here, approached Larry with the problem, and there was no active effort on his pr-jrt to "seek out" a situation leading to his retention. As to his response, "That person should see a lawyer," there was no intimation thereby that the person with the legal problem, still unknown to him, should seek HIS advice. Moreover, it is often preferable to suggest that legal cousel be sought, than to offer ad hoc advice without a complete investigation of the legal ramifications of the matter at hand. Often, minute changes in facts could render such advice improper.10 EC 2-3 provides, in part that " . . . the giving of advice that one should take legal action could well be in fulfilment of the duty of the legal profession to assist laymen in recognizing legal problems." (And in this connection, the ABA ". . . wishes to re- empha'sige. • .the importance of all lawyers' striving to make legal 12 services available within the bounds of professional responsibility." But once again, the test becomes laudable motivation, as further stated by EC 2-3: desire to tions. " * * * The advice is proper only if motivated by a protect one who is ignorant of his legal rights or obliga- Hence, the advice is improper If motivated by a desire to obtain personal benefit, secure personal publicity, or cause litigation to be brought merely to harass or injure another." Certainly, the advice to see a lawyer was prompted by Larry's professional judgment that the guest ultimately should be apprised of and have adequate representation of her legal rights. It could not reasonably be said that Larry was ill-motivated by publicity, a desire to harass, or even a desire for personal benefit. His was simply a response commensurate with the question put to him, nothing more and nothing less. offered his personal services, nor gave misleading He neither advice. Having resolved both the matters of solicitation and motivation in larry Lawyer's favor, there would seem to be to his handling the case. no further In fact, assuming (because impediment of the social context in which we find the interchange) that the guest was a personal friend of Larry's, DR 2-104- would suggest that Larry may accept the case, even though he might be precluded from doing so given another set of circumstances: ft "(A) A lawyer who has given unsolicited advice to a layman that he should obtain counsel or take legal action shall not accept employment resulting from that advice, except that: ."(l) A lawyer may accept employment by a close friend, . . This disciplinary rule would allow Larry to accept the curious guest as a client, were he a close friend, even if his advice had veen unsolicited. In conclusion, then, Larry's acceptance of the guest's offer to retain him on the case Is in no way violative of the CPR's Disciplinary rules. Her indirect approach in seeking his services in no way changes this. II. (RE: Church session on estate planning) It is well to recognize, before delving into the specifics of this second issue, that the United States Suprene Court has tended toward a recognition of an individual's "right to know" legal rights. It is suggested that such a right, like the associational right, may be derived as a logical extension of the First Amendment right to petition 13 the courts. Although the courts have not yet recognized this right as one of universal application, or even been cognizant of it with case respect to ej close in its facts to the present one, such a trend nevertheless lends added import to the fundamental goal of accessa- bility tc lawyers and the law. Its relevance here is only by way of giving due recognition to an undertone which is being in all the areas under the purview of' Canon 2. more widely felt That a favorable attitude towards being more "open is surfacing is indicated by the 1975 Proposed Changes in Canon 2, drafted by the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics, which evince a willingness to allow lawyers more latitude in advertising and publicity. It must not be overlooked, however, that the compiling need for the legal profession to serve the public has been long recognized. EC 2-1 explains: "The need of members of the public for legal services is met only if they recognize their legal problems, appreciate the importance of seeking legal assistance, and are able to obtain the services of acceptable legal cousel. Hence, important functions of the legal profession are to educate laymen to recognize 1L their problems . . .." EC 2-2 continues: "The legal profession should assist laymen to recognize legal problems because such problems may not be self-revealing and often are not timely noticed. Therefore, lawyers acting under proper auspices should encourage and participate in educational and public relations programs concerning our legal system with particular reference to legal problems that frequently arise. * * * Examples of permissible activities 15 include.; . .participation in seminars, lectures, and civic programs." "It is not only the right but the duty of the profession as a whole to utilize such methods fi.s may be developed to to those who bring the services of its members need them, so long as this can be done ethically and 16 with dignity." "We recognize a distinction between teaching the lay public the importance of solicitation of securing legal services and the 1r professional employment by or for a particualr lawyer." At first glance, then, the ABA apparently would condon larry's lecture to his church group. However, this is not a foregone conclusion, and more extensive probing reveals several difficulties. Vast obvious is the fact that most concern with sufficient availability of legal 18 services arises out of a concern for the poor or ignorant. 8 Assuredly, there is a need on the part of any segment of the public for legal services, but the members of the congregation to whom Iarry lectured were wealthy and therefore capable of paying for the same information on an individual bases. . Thus, the point in question becomes whether this in any wise makes the lecture any less desirable or less ethical or dignified. Certainly not. While concern for public need becomes more legitimate when talking about poverty, ignorance of the workings of the law is common to all socio-economic classes. And while the need, so often spoken of, may vary in degree and type, depending upon relative income, a legitimate need nonetheless exists. "law is not self applying; men must apply and utilize it in concrete cases. But the ordinary man is incapable. He cannot know the principles of law or the rules guiding the machinery of law administration; he does no know how to formulate his desires with precision and to put them into writing, and he is therefore ineffective 19 in the presentation of his claims." An added dimension is raised by the subjectmatter Larry discussed, viz., "benefits of giving appreciated stock, making intervivos gifts with a for public litigation. retained life estate, and so on." The concern education centers around the desirability of preventing "The obligation to provide legal services for those actually cqught up in litigation carries with it the obligation to make preventative legal advice accessible to all. * * * If it is not received in time, the most 20 court nay come too late." valiant and skillful representation in It can hardly be said that those topics discussed by Larry, have as their primary function the prevention of future litigation. But, estate planning is a matter of great concern to moneyed persons who wish to preserve their estate. .j And the need of the general public to have some understanding of how to give legal effect to their testimentary intentions is recognized by the ABA. "As a public service, the bar has in the past addressed the public as to the importance of making wills, consulting counsel in connection with real estate transactions, etc."21 Thus, after considerable discussion, there appears to be no real objection to either larry1s audience or his subjectmatter. We trun now to the more critical questions of self-laudation and the volunteering of services. "'Self-laudation is a very flexible concept; Canon 27 does not define it, so what course of conduct would be said to consitute it under a given state of facts would no doubt vary as the opinions of men vary. As a famous Englich judge said, it would vary as the length of the Chancelor's foot. It must be In words and tone that will "offend the traditions and lower the tone of our profession.1 it does this it is 'reprehensible.' which 'self-laudation' This seems to be is measured." said, Larry's conduct would be When the test by Based on all that has beeh reprehensible if his speech was 23 ". . . motivated by a desire to secure personal publicity . . .." DR 2-101: "(A) A lawyer shall not . . . participate in . . . any form of public communication that contains prefessional self-laudatory statements calculated•to attract lay cliets. * * * "(B) A lawyer shall not publicize himself, or his partner or associate, or any other lawyer affilliated with him or his firm as a lawyer through newspaper or magazine advertisements, radio or television announcements, display advertisements in or other means of publicity, nor shall city or telephone directories, he authorize or permit others to do so on his behalf. " (Empahsis added. Despite this, "(there is a recognized) distinction between teaching m the lay public the importance of securing legal services . , . and the solicitation of professional employment by or for a particualr lawyer. The former tends to promote the public interest, and enhance the public estimation of the profession. The latter Is calculated to injure the public and degrade the profession." 25 So, while educating the public is not only condoned but encouraged, an attorney so engaged 26 shoul "shun personl publicity-" speaks for the purpose Further, "A lawyer who writes or of educating members of the public to recognize their legal problems should carefully refrain from giving or appearing to give a general solution applicable to all apparently similar individual problems, since slight changes may require a material the vaiance in fact situations in the applicable advice; otherwise, public may be misled and misadvised. Talks and writings by lawyers should caution them not to attempt to solve individual 27 problems upon the In giving vasis of the information contained therein." his speech larry has not violated and of these boundaries. Would he be entering forbidden territory if he were to accept employment by the member of the congregation who had just listened to his 't speech and been At least there set impressed by his knowledge of the law? Is no disciplinary rule precluding it. out a general prohibition against a lawyer's employment Evidently not. DR 2-104- does accepting resulting from advice he has volunteered, but it is followed by an exception for cases such as this: "Without affecting his right to accept employment, a lawyer may speak publicly or write for publication on legal topics so long as he does not emphasize his own professional experience or 28 to give individual advice." bolstered his expertise or reputation and does not undertake There is no indication that Larry has responded to individuals' questions. Nevertheless, inasmuch as a lawyer's motivation is subjective and often difficualt to judge, Larry should weigh how his acceptance employment would appear to the public. of If it might look bad or make him suspect, he would do well to decline. III. (RE: legal check-up) Harry's implementation he sends periodic of a routine office procedure whereby letters to his former clients suggesting a "legal check-up" is not only ethically permissible, but a 195& study of the ABA Special Committee on the Economics of Law Practice recommended a concerted effort to get clients to have such checkups as a major step 29 toward improving lawyer income. "It certainly is not improper for a lawyer to advise his regular clients of new statutes, court decisions, and administrative rulings, which may affect the client:'s interests, provided the communication is strictly limited to such information. . .. "When such communications go to concerns or individuals other than regualar clients of the lawyer, they are thinly disguised advertise30 ments for professional employment, and are obviously improper." "It is our opinion believe that he has been that where the lawyer has no reason to supplanted by another lawyer, it Is not only his right, but It might even be his duty to advise his client of any change of fact or law which might defeat the client's testimentary purpose as expressed in the will. Periodic motices might be sent to the client for whom a lawyer has drawn a will, suggesting that it might be wise for the client to re-examine his will to determine whether or not there has been any chan in his 31 32 a modification of his will." ' 1am situation requiring FOOTNOTES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 12a. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. .—19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. ABA CPR, Canon 2. ABA CPR, DR 2-104. ABA CPR, EC 2-3. In re Ades, 6 F.Supp. 467 (D. Mary 1934). ABA Canons of Professional Ethics, Canon 28. ABA CPR, DR 2-103 B&C. ABA CPR, DR 2-130. ABA CPR, EC 2-3. ABA CPR, EC 2-5. ABA CPR, EC 2-3. ABA Formal Opinion 334 (August 10, 1974). ABA CPR, DR 2-104. United Mine Worker v. Illinois State Bar Association. 389 U.S. 217 (1967). ABA CPR, EC 2-1 ABA CPR, EC 2-2 ABA Opinion 320 (1968). ABA Opinion 179 (1938). Cheatham, Availability of Legal Services: The Responsibility of the Individual Lawyer and of the Organized Bar, 12 U.C.L.A.L.Rev. 438 (1965). Cheathajn, The lawyer's Role and Surroundings. 25 Rcoky lft. L. Rev. 405 (1953). Professional Responsibility: Report of the Joint Conference, 44 A.B.A.J. 1159 (1958). ABA Opinion 307 (1962). State v. Nichols, 151 So.2d 257,259 (Fla. 1963). ABA CPR, EC 2-3. ABA CPR, DR 2-101. ABA Opinion 179 (1938). ABA CPR, EC 2-2. ABA CPR, EC 2-5. See also, ABA Opinion 273 (1946). ABA CP^R, DR 2-104. ABA Informal Opinion 1288 (June 17, 1974). ABA Opinion 213 (1941). ABA Opinion 210 (1941). ABA CPR, DR 2-104 (A)(1). 13