Introduction Maxine Berg

advertisement

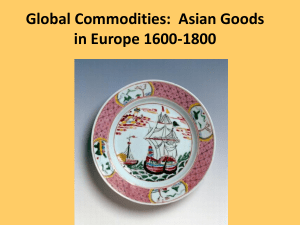

Introduction Maxine Berg Asian goods held a special fascination in European imaginations. Exotic and luxury goods were long associated with sensual oriental origins. Their significance went deep into social structures and cultural mentalities. Adam Smith saw the significance of ‘exotic baubles’ in shifting social structures and undermining the political power of the landed elites. He argued that ‘‘The discovery of a passage to the east Indies, by the Cape of good Hope, which happened much about the same time, opened, perhaps, a still more extensive range to foreign commerce than even that of America, notwithstanding the greater distance…Europe, however, has hitherto derived much less advantage from its commerce with the East Indies, than from that with America’.i Jan de Vries, more recently, has found their power among the factors motivating significant changes in the household behaviour of North Europeans, thus generating an industrious revolution that went on to foster industrialisation. How irresistible were these goods, and how long did this last? The oriental curiosities that found their way into the cabinets of Europe’s early modern and Renaissance elites became by the Eighteenth 1 Century the products of a systematic European and Asian trade reaching a wide consuming public. A trade conducted by Europe’s monopoly East India Companies and myriad private traders made the difference, and provided a whole new level of interaction. Asian-sourced consumer goods designed for European markets were to become seamlessly embedded into European material cultures. This book brings together leading historians and early career researchers to offer new insight and fresh materials on the trade in Asian goods and how these affected Europeans. Scholars who have researched colonial and Indian Ocean trade join those working on European consumer cultures and industrialisation. Established scholars from Jan de Vries, Om Prakash and Jos Gommans join a new generation of researchers investigating the connections between European consumer cultures and Asian trade. The fascination of Europe’s monarchs, courts and elites with the fabulous wealth, exotic flora and fauna and exquisitely crafted fine luxury goods goes back to the Bronze Age. The opening of the sea routes to India and China from the end of the Fifteenth Century changed the game, and by the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, Northern Europe had established its famed East India Companies to ply a regular commerce to India, South East Asia and China. The surprise packages that filled the cabinets of curiosities of Europe’s elites were displaced over the course of the eighteenth century by 2 the cargoes, auctions, toy shops, drapers, china shops and pedlars that brought Asian export ware onto the bodies and into the cupboards of Europe’s merchants and townspeople. We are only now uncovering how deeply these goods penetrated European social structures, and especially now beyond those core regions of Britain and the Netherlands. Earlier approaches to European connections to wider world histories focussed on issues of colonialism, empire and the slave trade. They recounted the economics of trade flows, commodity chains and the politics of colonial domination. They gathered data and analysed the flows of British exports to India and China, as well as to Africa and North and South America. Historians have debated the extent to which these trade flows both provided large external markets for Britain and Europe, and hindered industrialization in many parts of the world. Our histories have, however, given far less consideration to the impact especially of Asia on European material cultures. Goods from the East benefits from recent research on the material culture of the early modern period, from new work on the East India Companies, and from the opportunity provided by a large project, the European Research Council-funded ‘Europe’s Asian Centuries: Trading Eurasia’ to bring these fields together. Goods from the East investigates the trade in products: how they were made, marketed and 3 distributed between Asia and Europe. It addresses the impact of the first Global Age as this affected Europe in terms of its manufacturing and consumption. The questions it raises relate closely to issues of fine manufacturing and luxury goods in the current age of globalization. A key problem for European economies of the early modern period was how to turn the human desire for superfluous things, for fashion, for exotica into something that could civilise and improve national economies rather than lead them into moral decline and corruption. The whole imperative of the long-distance seaborne trade of Europeans from the age of exploration was to acquire the goods of the exotic East – the silks and porcelains of China, the spices of the spice islands and India and India’s textiles. The encounter of early empires with precious and exotic decorative arts was turned into an intensive and systematically-organized trade in high-quality export ware sourced in Asia. This was conducted and lubricated via the East India Companies and associated private trade. This trade in turn, fostered new industries and consumer practices in Europe, and economic policy commentators and enlightened writers were well aware of this. The Abbé Raynal wrote in 1777: ‘If Saxony and other countries of Europe make up fine China’, if Valencia manufactures Pekins superior to those of China; if Switzerland imitates the muslins and worked calicoes of Bengal; if England and France print linens with 4 great elegance; if so many stuffs, formerly unknown in our climates, now employ our best artists, are we not indebted to India for all these advantages?’ii Yet the connection of European markets with the consumption of Asian luxuries and other commodities was not a given and automatic response to trade. Those markets were built, the impact of the goods was diverse across Europe, and the conditions of trade entailed an integrated European and Asian commerce. Scholars working on several different European countries as well as on India and China give us insight into the differences in the structure and impact of Asian goods as well as into the complexities of interactions among Europeans and Asians engaged in the trade. Goods from the East engages with new historical approaches arising from global history; it develops subject areas grounded in skills and processes of production as well as material culture, and it demonstrates the new depth of research into diverse markets, quality differences and the development of taste. That depth of research is also frequently at a local level: local sites of production, key events of reception and adaptation. Recent historians have gained access to these through microhistorical perspectives on individuals and families, as well as the local worlds that contemporary travellers and writers recounted and left behind. 5 Global history brought into the historical mainstream large scale comparative histories of China, India and Europe. Debates on the ‘great divergence’ made China, then India the focus of comparison, challenging assumptions of European dynamism and static Asiatic economies bound in traditional cultures. Ken Pomeranz and others gathered argument and data to demonstrate that Europe’s divergence was based on environmental factors, notably a new energy efficiency gained in the use of coal. Trade, in this debate, played no part in ‘divergence’. Europe was compared, but not connected to the rest of Asia. Accounts of trade and colonialism, for their part assembled the data of commodity flows and recounted histories of imperial domination. But there has been little sense of the products that were traded, how they were made, then marketed and distributed in Asia, en route from Asia, and in Europe. In the recent decade these objects have been the new focal point in the galleries and exhibitions of the world’s museums, and are the subjects of a new attention among historians to material culture, including the skills, design and materials of objects as well as their use, display and symbolism. Recent books convey this new direction: The Pilgrim Art: Porcelain in World History (Finlay), The Colour of Paradise. Emeralds in the Age of Gunpowder Empires (Lane), The Dress of the People (Styles). A new sensitivity to the diversities and 6 qualities of things, and cultural issues over their reception, negotiation or refusal are now important to our wider histories. Cross-cultural production and use of objects form an equally important aspect of ‘global connections’. A real strength of this volume is the degree to which many of its chapters engage in the diversity of goods and their qualities. The choice of goods and the development of the taste to display and use them were fundamental to the success of this Asian trade. Objects, furthermore, provide a method of global history. They provide the opportunity of a different perspective, a different point of view. Detailed accounts using those approaches of method and scale arising from microhistory help us to analyse objects perceived as ‘strange’ or brought from a distance, and thus to raise new questions for the ‘local’ and the ‘global’. Many of the contributors to the volume have the experience of working with museum objects and they have drawn on the curatorial approach as well as wider histories The book takes up the following themes: • The Scale and Significance of Asian Exports • Objects of Encounter and Transfers of Knowledge • Private Trade and Networks 7 • Consuming East and West • A Taste for Tea • Luxuries and Consumers in Early Modern Dutch Cities and Indian Courts In an opening chapter on the Scale and Significance of Asian Exports, Jan de Vries discusses the extent to which these goods were luxuries, or goods that reached deep down through European social hierarchies. They were among the goods that prompted the ‘industrious revolution’. The many push and pull factors of declining costs of Eurasian trade, political economy in Asia, rising incomes and urbanisation in Europe certainly provide good reasons for a trade boom in Asian export wares. But possibly even more significant were the new information flows brought with the trade in goods: new knowledge of goods, new tastes and preferences, and new commercial information. Objects of Encounter and Transfers of Knowledge have provided a focal point for recent cultural historians and historians of science and technology. The six chapters of this section follow the early uneasy relationship of trade and diplomacy into the development of Asian technologies and resources adapted to Europe’s markets. They also follow attempts to transfer 8 technologies between Asia and Europe: cases range from indigo and dyes to textiles and metal processing, porcelain enamelling and information transmitted through passed in models and pattern books. Private Trade and Networks introduces us to the significant place of private trade operating in tandem with monopoly companies in conveying not only specialist and luxury goods, but tea, textiles and porcelain at various stages of trade and distribution. Four chapters convey the participation of Company merchants in private trade, the trade in specialist luxury goods, the part played by the diamond trade and comparison between the Dutch and the English incorporation of private trade. Consuming East and West shows us the wide European markets for Asian products. Not just elites, but middling class consumers sought the fashion, civility and status that such goods conveyed. New research in inventories, pauper letters and the records of foundling hospitals and orphanages, archaeological sites, and criminal records provide a wide social perspective to this trade. The section introduces five studies of Dutch and French smuggling, advertising, retailing and consuming Asian goods, including the consumer cultures of the French community in India. A Taste for Tea provides new insight into the tea trade, one of the most pivotal parts of East India Company trade. Paradoxically, the tea trade has 9 hitherto been relatively neglected by historians. Over the later Seventeenth and early Eighteenth Century, tea imports increased steadily, amplified by smuggling. So much so that by the 1770s smuggling dominated this trade. In 1783 the legal tea in East India Company warehouses was valued at £5.9 million compared to the £7-8 million smuggled in. The Tea Commutation Act of 1784 reduced the duty from 119 per cent to 12.5 per cent, and legal tea in the warehouses in the course of the following year rose to £16.3 million. Three chapters tell a Northern story of an innovative trade led by the Ostend, Swedish and Danish Companies, the incorporation of a culture of hot drinks into Netherlandish society, and another Northern story of sophisticated smuggling networks that spread tea drinking through remote parts of Scotland. A taste and trade in high quality teas were developed, and tea drinking and other Asian goods were domesticated and neutralized within Scottish and other European consumer cultures. Luxuries and Consumers in Early Modern Dutch Cities and Indian courts, a concluding chapter by Jos Gommans, compares the recent histories of consumer culture, including the taste for Asian goods in the Dutch Republic with consumer practices in Indian courts during the period of rapidly expanding Indian Ocean and global trade. 10 Adam Smith, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations (1776), ed. A.S. Campbell and A.S. Skinner, (Oxford, , 1976), 2 vols., Vol. 1, Book IV, chapter 1, p. 448. i ii Abbé Raynal, The Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies (1776), vol. II, p. 288. 11