AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF (Name) (Degree)

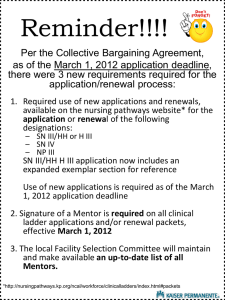

advertisement