for the presented on August 9, 1968 Agricultural Economics

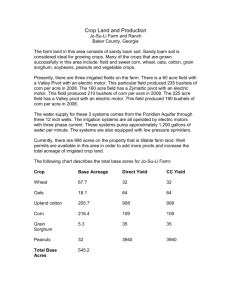

advertisement