Abandoning Standing: Trading a Rule of Access

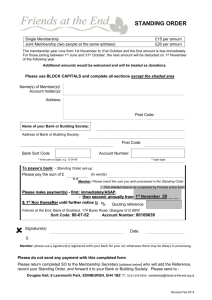

advertisement