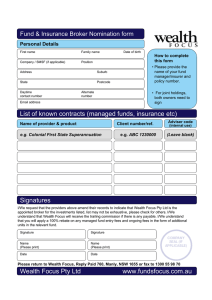

B P R ?

advertisement